A Young Man's Fancy and An Old Man's Disdain

It's a tale of possibly the greatest baseball player to have ever picked up a bat, ball, and glove, and he came from an obscure little spot in a bend of a Texas river. Or we could just talk politics...

(I think I am beleaguered trying to stay apace the craziness of American politics and the strife tearing at the wider world. As I was pondering a topic for this week's piece, I thought with disgust of Tucker Carlson, a pseudo-journalist who managed to interview Vladimir Putin without asking hard questions about the war against Ukraine or the treatment of Alexi Navalny, who stood fearlessly against the dictator’s oppression. Carlson later explained to those of us less wise and sophisticated as he, “Leaders sometimes have to kill people.” He never mentioned that murder is easier when no one calls the politician to account.

(I also considered writing about Trump’s speech to Black voters and the absurdity of his attempt to associate himself with the struggle of African Americans. A conservative crowd of Black Republicans heard him claim that he was like them, “Because I’ve been indicted, too.” The insult never occurred to his Adderall-addled brain that he had just stereotyped a demographic by implying it was comprised of only people who had troubles with the law. I expect the K-Mart version of a dictator is about to have another lousy week because the only sane ruling the Supreme Court can offer regarding his claim of immunity is to refuse to hear his case and let the D.C. lower court’s ruling stand. Even a radically conservative majority will be cornered by the law on that case. Also, if Trump wants to appeal his civil court judgment in New York, he has to post bond to guarantee payment, or put the entire $454 million plus interest into an account, pending a judgment on his further arguments. Good thing he is delusional because otherwise, Trump’s travails might make him crazy, I mean, of course, crazier, if that is possible. He seems to be pegging the needle, right now.

(House Speaker Moses has been bugging me a lot lately, too. It is not hard to make an argument that the fate of the Western World might rest on the leadership of a man who claims to speak to god and refuses to move legislation that would provide funding to Ukraine in its war against Russia. Without U.S. financial support, Ukraine will almost certainly fall to Putin, and he will take the West’s weakness as a clue that NATO’s biggest member can no longer be counted on to deliver critical resistance to Russia’s geo-political ambitions. The Speaker acts almost afraid to bring up the legislation because he’s clearly concerned he might anger the edge-of-earth coalition on the right, who will refuse to support the measure or take a procedural vote to get him out of office. Who knows what Speaker Moses’ god thinks about those wrong moves?

(Gaza is also haunting my sleep. Increasingly, people who offer political resistance or criticism of Israel are being branded as anti-semitic, which is a rhetorical crock. There will be no Gaza when Netanyahu is finished, and the tiny population of survivors will be displaced to other countries or surrender to living under a permanent IDF rule, if and when the narrow strip of real estate is rebuilt for human habitation. No one has to search far to find stories and evidence of war crimes and acts committed by IDF soldiers that are every bit as brutal as those described when Hamas attacked Israel.

(Facts, as in every war, are elusive, but a report by the Committee to Protect Journalists indicates 88 reporters and media workers have been confirmed dead, and 83 of those were Palestinian. Four are said to be missing, 16 injured, and 25 arrested. There are also long lists of claims of threats, intimidation, and violence, which is why Western reporters and TV networks have little, if any, resources on the ground in Gaza. Americans have no real sense of the tragedy that is Gaza, which is probably exactly what is desired by Netanyahu and the IDF. Americans are largely oblivious to the ongoing horrors.

(The number of children killed as I write this on Feb. 24 is 12,660 while 8,570 women have become casualties of IDF’s invasion. Those are the numbers since the Oct. 7 attack by Hamas and they are, astonishingly, six times higher than the figures for the two-year war in Ukraine. The Gaza Health Ministry says the total of all dead is just under 30,000 as of this date. If the U.S. President does not demand, and get, a cease-fire from Israel, all military support ought to be terminated, though that hour seemed to have arrived months ago.

(Well, I guess I lost my way because I was going to try to concentrate on Spring Training and baseball. Feels like summer has already arrived in the Texas Hill Country, which has prompted me to revisit, and revise a bit, one of the most popular things I have written in my almost three years here on Substack. It is a tale of possibly the greatest baseball player to have ever picked up a bat, ball, and glove, and he came from an obscure little spot in a bend of a Texas river. If you are a baseball fan, and don’t know of him, you should. I realize this is quite a jump from the brutal complexities of geopolitics detailed above, but maybe the story of Rogers Hornsby can act as a bit of an informational and emotional curative on this hot and sunny weekend in Texas. - JM)

“A ballplayer spends a good piece of his life gripping a baseball, and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.” - Jim Bouton, baseball pitcher and author of “Ball Four”

While the Indian paintbrush and bluebonnets color the banks of the Colorado, may I suggest you follow old Webberville Road east of Austin out where the river makes a few horseshoe twists coming down from the Hill Country and marking its water course through the black land prairie out toward the Coastal Bend. This little ride, for me, is a rite of passage when the seasons change. Make sure you look for a sign indicating the Hornsby Bend Cemetery, or stop and ask directions. Everybody who has lived there for ten minutes knows its location. Significant people in the history of Texas rest there not far from the river. One of them is, arguably, the greatest baseball player to ever put on a big league uniform.

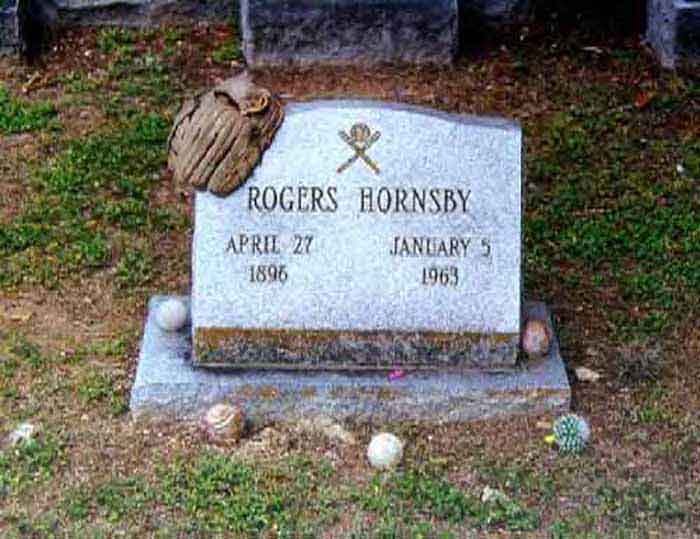

Spring is the optimal time to visit the grave of Rogers Hornsby, who still retains the highest batting average ever recorded in the big leagues. He is buried in a modest cemetery not far from the bend in the Colorado, which is named after his family. Often, an admirer will have left a perfectly useful baseball glove atop Hornsby’s grave, and his headstone will be easy to spot. Hard to think the old ballplayer might be willing to abide the abandonment of a good fielder’s mitt, but they show up, nonetheless.

The Hornsbys were important actors in establishing and the development of Texas, though the state takes little note of their history or signal accomplishments. Rogers, whose first name was his mother’s maiden surname, rests not far from Reuben Hornsby, the family patriarch, and one of the founders of the Texas Rangers. Reuben had been given a grant of land in Texas by Stephen F. Austin. He was a surveyor and with his wife Sarah settled on the north bank of the river and began the first community in what later became Travis County. Hornsby, who, eventually, helped to survey Austin for the capital of the Texas Republic in 1839, also was father to the first Anglo child born in the county, sat on the initial jury in Travis County, and even grew the initial crop of corn. Twelve members of Hornsby’s family became Texas Rangers and are also buried in the cemetery. And one of Reuben Hornsby’s descendants became a player many baseball experts argue is possibly the most talented to ever grip the rawhide or run out a ground ball.

Rogers Hornsby was born in Winters, Texas, a dusty spot on the edge of the Edwards Plateau, just over forty miles south of Abilene. After his father’s death when Rogers was just two years old in 1898, his mother moved the family to the Austin area, which was just a few miles up the Colorado from where his grandfather had settled Hornsby’s Bend. The family, eventually, returned to Fort Worth for work but by the time he was fifteen, Rogers was playing semi-pro baseball. When he entered the big league while still in his teens, he helped to launch the managerial career of Branch Rickey, the man who later made Jackie Robinson the first African American in pro baseball.

Hornsby, who said he could remember nothing about his life before he held a baseball in his hand, played in the “dead,” and the beginning of the “live ball” eras. But he hit most everything, regardless of its resilience against wood. Only Ty Cobb has a higher career batting average of .367, and Oscar Charleston of the Negro Leagues, who hit for a .364 mark. Hornsby batted .358 over his career of 23 seasons and earned two Triple Crowns, batted .400 or better three times, and in 1924 hit a .424 average, which remains the highest B.A. in MLB history. He is also the only player to hit .400 and get 40 home runs in a single season.

But he was not considered much of a convivial or pleasant fellow. Teammates did not care for Hornsby, who never drank, smoke, or went to the movies. His belief was that the moving pictures might damage his eyesight. Hornsby gambled on horses, though, and lost a lot of his earnings as a ballplayer. He was also married three times, but lived for baseball, which might have strained any personal relationship outside the diamond. No less a legend than the “Splendid Splinter,” Ted Williams said Hornsby was the greatest hitter for power and average who had ever played the game, and Frankie Frisch, a player and manager in the big leagues, described Hornsby as the “only guy I know who could probably hit .350 in the dark.” He won seven batting titles and one World Series, which ended when Hornsby tagged out Babe Ruth trying to steal second base. The Texan was sufficiently obsessed with baseball that when his mother died during the World Series, he had her funeral delayed until the contest had concluded.

There are ball diamonds along Webberville Road today, not far from where Rogers Hornsby rests, and there are boys and men still playing the game on those crude fields mowed into pastures. Even in its unpolished form, we can assume that Hornsby passing by would have loved what he saw of players enjoying a contest with their withering muscles and misguided throws. Many of them have no idea of the greatness that once passed through that little settlement on the Colorado River, not much more than a long throw from where they are shagging fly balls each Spring. My senior men’s team, a few years back, took our spring training on a quite nice private field only a few miles from where the great second baseman is buried.

I was always hopeful, as baseball will make a man, of a good season, warm weather, and a happy life every spring as I drove through Hornsby’s Bend on my way to practice. I wished there was a way to measure the joy of my anticipation. I confess, too, that I wondered what Rogers might think of our skills after our too many decades, but I am sure he would have understood our undying love of a game that connected us to our youth and the power of hope and annual renewal. I also frequently thought of what Rogers told a sportswriter that had kept pestering him about who he was and what he did to occupy his time when the weather was cold and he wasn’t playing the game.

“People ask me what I do in winter when there’s no baseball,” he said. “I’ll tell you what I do. I stare out the window and wait for spring.”

Is there a better way to express a love of life, and its grandest game?