Independence Way

I understood that there were economic and educational forces at work that made our lives abundantly different. My mother carried burgers and open-faced sandwiches as a waitress at a short-order restaurant. My father lifted bumpers out of a metal press for delivery to the assembly line.

There was a line, but we pretended it did not exist. That was the best way to get through each day as we came of age. In our factory town, there were the laborers and the management, and the families in our neighborhood supplied the muscle and bone to build the cars rolling out onto the American road. Mostly, our fathers were from below the Mason-Dixon Line and bending their backs to an assembly line felt like no great chore and paid immensely better than chopping cotton. Until the unions, laborers could not afford to own what they built for others.

A great, gray factory separated our fortunes. After World War II, it had begun manufacturing cars but retained its name as the Tank Plant. Sherman tanks were assembled, tested, and shipped out of the facility in Southern Lower Michigan. Great pride was taken in delivery of the armored attack vehicles to Allied troops moving across the European and African continents. Blue collar workers of both sexes, not carrying guns, felt the importance of their contributions. The families living on our side of the vast structure, after the war, were the welders and fabricators and drill operators and people with modest skills and growing families.

Managers of the workers, foremen and shop executives, and businesses that thrived by serving the factory’s needs for raw materials and services, lived on the other side of the Tank Plant. Their homes were middle and upper middle class but when we were inhabiting 800 square feet tract houses, the contrast was startling. I did not ever enter those grand houses, except for rare moments when invited by a classmate, and I was always afraid to brush against the wall and looked at my feet to make certain I did not track the floors. In one of the wealthiest neighborhoods, there was golf course that held a big professional tournament and as I dragged my pro’s bag around the course I looked at the magnificent homes that lined the fairways and wondered how such money was accumulated.

I had no understanding of how class distinctions evolved, or why my situation was so dramatically different from the overwhelming majority of the other students in my school. When I saw them in their new cars and down jackets in the winter time, though, I understood there were economic and educational forces at work that made our lives abundantly different. My mother carried burgers and open-faced sandwiches as a waitress at a short order restaurant and my father lifted bumpers out of a metal press and stacked them on pallets for delivery to the assembly line. Neither ever drew a breath without worrying about money, how to pay for school clothes, the oil delivery truck that filled up the tank out back to run the furnace in the middle of the house, groceries, electricity, and the burdensome monthly mortgage of $62.50 on a $10,000 VA loan.

I only have memories of wanting to leave and five decades later I still do not want to go home, though I infrequently visit. Our little house had neither space nor money to make life enjoyable and when the snow piled up the window frame and we were unable to leave, I felt as if I might be trapped for the rest of my existence. When the roads became passable after a blizzard, we often wore old socks on our hands for gloves and stuffed them into our pants pockets before we got off the bus at school because we did not want our classmates to know our modest deprivations. Such humiliation is hard to endure when both of your parents are working 60-hour weeks and still cannot afford to properly clothe their six children. I was angry because I listened to too many people talk about opportunities my struggling parents never encountered in their American life.

To get away from all this, I took to the highway when I graduated high school at age seventeen. I was less afraid of strangers on the road than I was of my father’s thundering right hand or his snapping razor strop and the kitchen drawers he tossed through the living room window when he could not control the anger he possessed because of how his life had unfolded. These were factors I was unable to explain to drivers who stopped to offer a ride when I stood by the pavement with my thumb cast into the traffic. I did not want to offer up any background, I just wanted to put miles of road behind me and keep moving westerly. The questions kept recurring, though.

“Hop in kid. Where you going?”

“Out west. Maybe California, if I can get there.”

“What the hell’s wrong with you?”

“I’m sorry. I don’t know what you mean.”

“You look like you weigh maybe 140 pounds. Somebody could hurt you. Do your parents know what you are doing or where you are going?”

“My mother does. She cried when I left, but she knew I had to go.”

“Why’d you have to go? You like sleeping under bridges and in cornfields more than sleeping under the roof at your parents’ house?”

“No mister, but it ain’t that simple. Honest.”

I remember that conversation with a trucker near Scottsbluff, Nebraska, out near the Wyoming line. He was not just big in the middle like a man who sat and ate and worried all day but his arms were large with rounded muscles and the more questions he asked the more afraid I became. When he stopped talking, he kept looking over at me as if he were making an assessment as to whether I was crazy or if I might be able to escape. I never knew which.

“Hey, can you let me off up here, a few miles down the road? I kinda want to spend time in Wyoming, hiking around.”

“What for?”

“I like history, you know, westward expansion and that stuff. I want to see that Independence Rock that’s around here somewhere. Lots of people traveling on wagon trains left their names and initials carved into the rock. There are even still ruts where all the wagon trains went by.”

“Okay, kid. Whatever you want. But you sure?”

“Yeah, yeah. I’m sure.”

He reached across the bench seat in the cab and patted my knee. I did not look at his face but I wanted out of his truck.

“You can go all the way to California with me, if you want. I could use the company. I’ll get you a few meals, too. Road gets lonely when you live on it.”

“No, no,” I said. “I’ve got to get off here. I’m doing research, see, about Manifest Destiny, you know, when all the Europeans went over the mountains and wiped out the Indians on the way.’

“Manifest destiny, huh? Okay, kid. Whatever ya want.”

The truck slowed in the breakdown lane and my hand was on the metal frame of my backpack before he had engine-braked to a full stop. I opened the door and dropped the nylon pack to the ground, thanked him quickly, and jumped out behind my gear. I reached up and swung the passenger door closed and heard the air brakes hiss as he released them and dropped the cabover into gear.

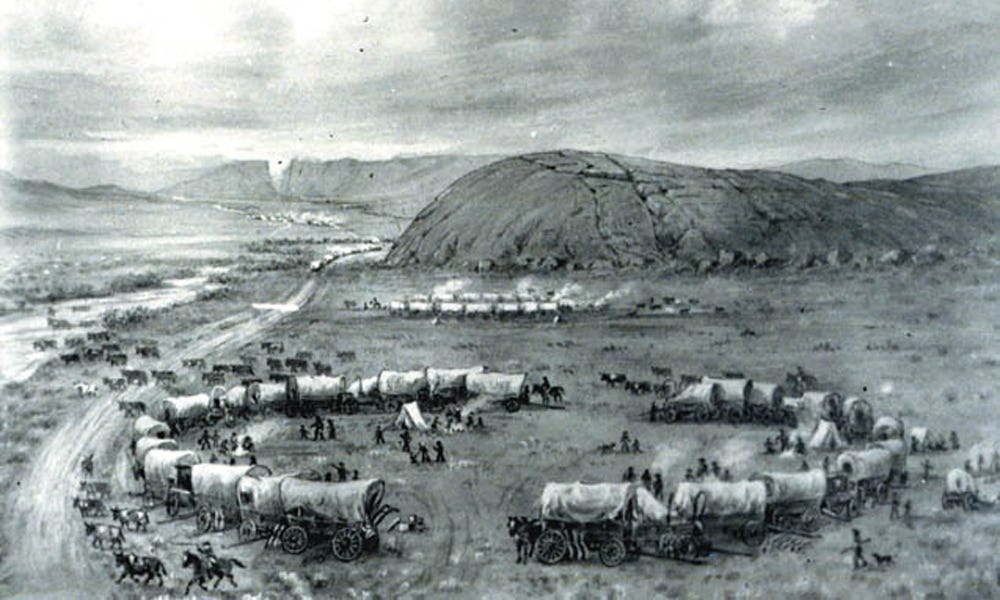

I walked away from the Interstate and did not look back because I wanted to be certain the 18-wheeler was moving west with its load of refrigerators. About five minutes later, I turned around and went back and quickly got a ride in the bed of a pickup that was going south of Casper toward Independence Rock. When I finally jumped over the tailgate and onto the road, I was disappointed at the famous formation I had read about in school. I thought it looked a bit like a giant turtle and was oddly insignificant to have become a place of such import in American history.

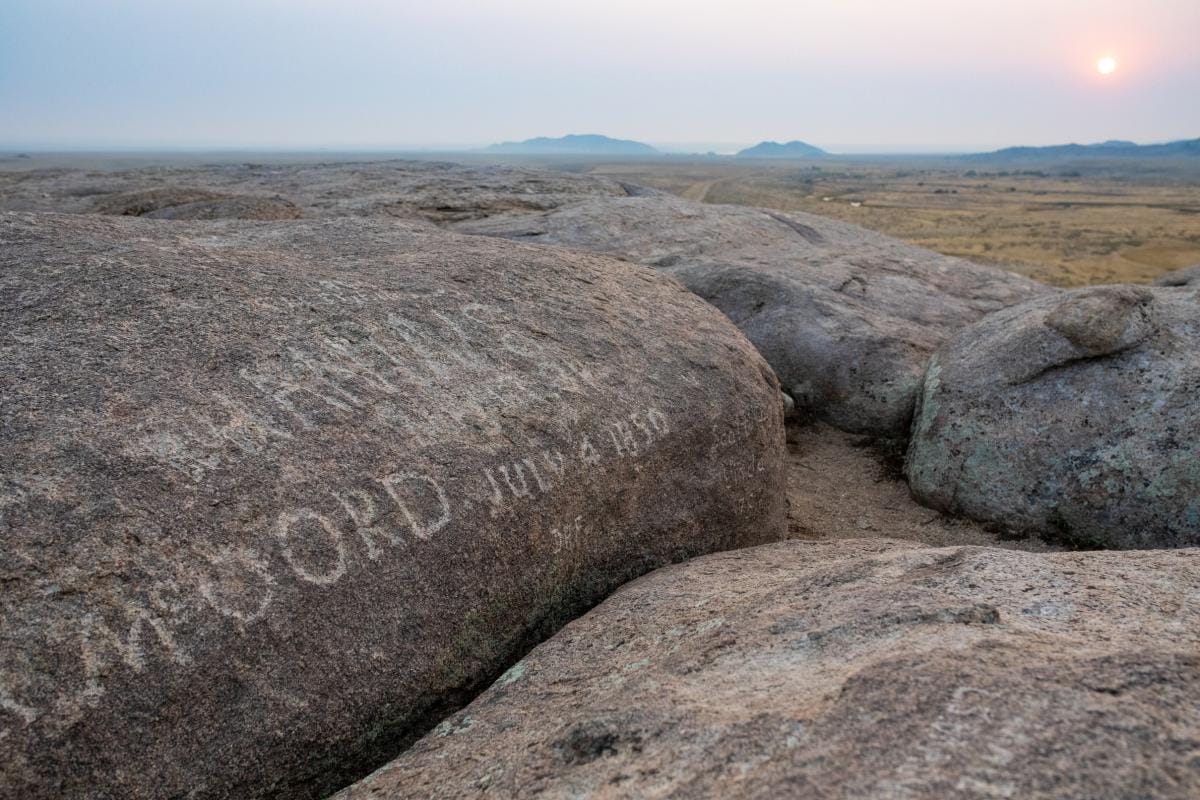

The rock was covered with the names of an estimated 5000 travelers who had moved past it on their way west during the 1800s. I had already begun to think if it as a place of hope because every wagon train that had gone west from Fort Laramie included people who had survived attacks by indigenous peoples, endured winds and rain and floods and hunger, but had pressed onward to whatever they had envisioned might exist for them in Utah or the Willamette Valley or the California coast. The granite outcrop became a kind of bulletin board for travelers on the Oregon Trail, who carved inscriptions of their names and dates and observations as they began the long, dangerous climb toward the Great Divide.

On July 26, 1849, J. Goldsborough Bruff

"…reached Independence Rock . . . at a distance looks like a huge whale. It is being painted & marked every way, all over, with names, dates, initials, &c - so that it was with difficulty I could find a place to inscribe it."

The name was derived from a Fourth of July celebration at the site in 1830 by a group of fur trappers. Even as a 17-year-old in his first summer of wandering, I knew I was in a spot both sacred and profane. The Plains Indians certainly did not want to tolerate the strangers transiting lands they had roamed freely in time beyond memory and they often fought desperately and futilely to stop the increasing numbers of white transgressors. The emigrants, though, were too numerous and did not stop coming and their determination outweighed their fears. The trail was also fraught with perils of disease like small pox and yellow fever and dysentery from bad water, and had claimed thousands of lives, but the survivors remained hopeful of a life they were barely able to describe or define.

Even though I wondered if there were ghosts still hovering nearby, the spirits of travelers who had died with their unrealized aspirations somewhere near the rock, I still walked off to find a place to unroll my bag and sleep. There did not seem to be many tourists about and traffic was hurrying to bigger national parks with grander views. I belonged where I found myself at the end of that day. I, too, was determined to make it over the Divide, if only by hitchhiking the next morning, but as my eyes grew heavy and the wind came down off the Rockies, I was also unable to see my future. I felt, though, the power of all the hope that had led those souls of long ago to that rock.

And I was anxious to move further west.