The Way We Were

For the first half of the 20th century, summers were not carefree for children or adults. Swimming pools were often shuttered, playgrounds empty and quiet, and parental dread informed every decision about their children’s activities. The polio virus invisibly stalked the world...

We put Scotty at first base because he was unable to really run. Whenever he tried, his withered left leg appeared to move out of his control, touching the ground without purpose. In Little League, and neighborhood pickup games, we gave him a pinch runner, which he hated, but his love of baseball was greater. Scotty was stronger and taller than the rest of us in ten-year-old ball and he often drove deep fly balls up against the fence. Because his hits often traveled so far, the boy who ran for him could walk to second base without trouble, if he did not feel like sprinting around the bases.

In the summers up in Michigan, Scotty wore shorts and was unafraid of showing his leg. There seemed almost more bone than muscle but he was always participating in sports, which I did not understand. He was one year younger than me and I did not think I could have accepted the occasional humiliation or personal frustration that he had to feel when his body refused to let him do what he wanted. His arm muscles were disproportionately large compared to even his healthy leg because he often used a wheelchair, and he clearly enjoyed affecting a baseball game with his long drives. I saw him cry once, though, when he hit a home run over a short left field fence and our teammates all jumped up and down around the pinch runner and ignored Scotty, as if he were not even involved.

He had been afflicted with the polio virus. None of the kids in our neighborhood ever talked to him about it and how he had acquired it, but he was born in 1952, which was the year of the worst U.S. outbreak, accounting for about 57,000 reported cases, 3,145 deaths, and more than 21,000 people paralyzed. For the first half of the 20th century, summers were not carefree for children or adults. Swimming pools were often shuttered, playgrounds empty and quiet, and parental dread informed every decision about their children’s activities. The polio virus invisibly stalked the world, and a half dozen of my classmates limped through the hallways of our elementary school.

A vaccine might have saved all humanity. A researcher named Jonas Salk “killed” the virus and began injecting it into nearly two million people, who became known as “Polio Pioneers.” It was the largest medical experiment in human history and was known as the Francis Field Trial. Randomized, blinded methods were employed where both placebos and the vaccine were injected across hundreds of communities. Three years after my little league teammate Scotty had been born, the results of the experiment were announced just down the highway in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The news came on April 12, 1955, that the vaccine was “safe, effective, and potent.” A short time later, church bells began to ring out across Michigan, and big, block newspaper headlines announced the next day, “POLIO IS CONQUERED.”

Unlike today’s disturbing conservative skepticism of science and medicine, news of the Ann Arbor announcement spread instantly by radio and newspapers. Canadian cities organized ceremonies similar to U.S. parades, and European headlines called it a “miracle.” The London Times hailed Salk’s work as a breakthrough for all humanity, and even in the midst of the Cold War, media in the Soviet Union portrayed Salk’s discovery as a triumph of international scientific cooperation. Parades were not as common in the U.S.S.R., but the rollout was accompanied by large public ceremonies and propaganda campaigns. Salk did not get rich from his genius, either. When asked by CBS’s Edward R. Murrow, who owned the vaccine, Salk answered, “Well, the people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”

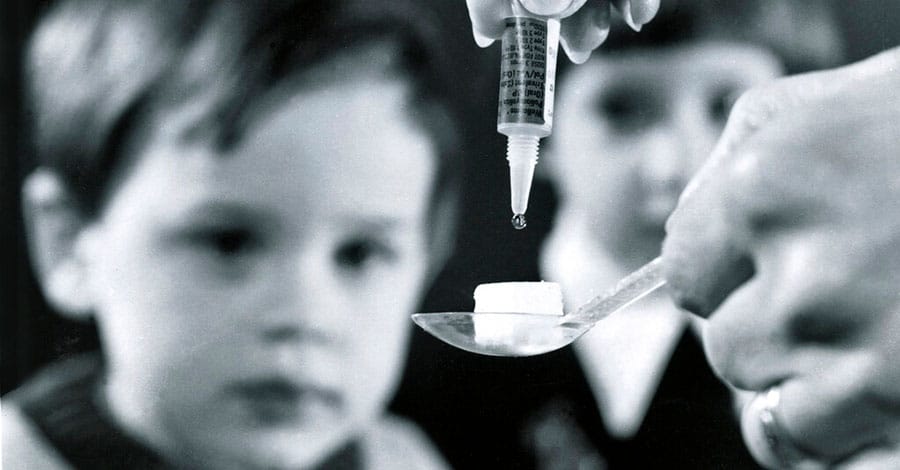

Mass childhood vaccinations began all across the land. There were injections in schools and community clinics, and, eventually, an oral vaccine delivered in a sugar cube. I was never afraid of polio because I assumed, as did most children, that it was rare and that we were not all exposed. Our classrooms, one day, were emptied in a controlled order and we went to the cafeteria and stood in line and were handed a sugar cube, which nurses made sure we dissolved in our mouths and swallowed before we were allowed to return to our desks. I was more frightened by nuclear bomb drills than an invisible virus, and often lay awake in bed at night awaiting a Soviet attack, which was my emotional response to being ordered to hide under my school desk when an alarm bell sounded.

Before Salk, there was no cure for polio. Victims were given supportive care like hot packs and assisted movement or isolation. If breathing muscles were paralyzed, patients were placed inside an iron lung. Within a few years of mass vaccination, though, paralytic polio plummeted in the U.S. and by 1979, the last case of wild poliovirus in this country was recorded. All the Americas were declared polio-free in 1994. Globally, according to the CDC, cases have fallen by more than 99% since the vaccine era began. From the moment the news spread across the planet, there has been relief and gratitude, which contrasts greatly with partisan influence over research and vaccines by the far right. Republicans tend to believe vaccines should be a parental choice, an absurd notion that would expose other children to the proliferation of disease. Skepticism is overcoming the joy delivered by science and medicine.

We live now in an age where the Trump-appointed director of the CDC, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., amplifies vaccine safety allegations and has suggested that a common painkiller, acetaminophen, is the proximate cause of autism, though there is zero research. Despite extensive evidence to the contrary, there continues to be an unsubstantiated narrative that the MMR vaccine can create autism in children, and such rumors have a wide influence among an uninformed subset of conservative voters and independents. If RFK is not dismissed from the CDC and control returned to physicians and scientists, the future is readily predictable. We got a glimpse through a glass darkly earlier this year when an anti-vax Mennonite settlement in West Texas refused to allow their children to receive the MMR triple jab, and measles killed two unvaccinated children in Texas and one adult in New Mexico. There were 762 people infected, with 99 hospitalizations, an outbreak that significantly contributed to a troubling resurgence of measles in the U.S. There were 1,356 confirmed cases nationwide by early August 2025, which was the highest total in over 30 years

The low-intellect anti-vax movement appears destined to gain more influence and control under a president who once suggested bleach or horse tranquilizers or infrared light inside the human body might kill the Covid virus. More people will die because complacency invites disease comebacks. In 2022, a paralytic polio case arose in an unvaccinated adult in New York City, and the virus was detected in nearby wastewater. Viruses are smarter than politicians, and they exploit gaps in immunity. More outbreaks are inevitable, and the herd, not protected, will trot off into historic ignominy. As they draw their last breaths among a field of dead children, they can take solace in the fact that they won the political argument.

And lost our future.