Adventures of a Young Man: Starting Out in the West

“You need a tape. Nobody will hire you without a tape.” The DJ struck me as a leather-sandaled beer keg in a tie-dyed tee shirt, but he had a voice that suggested death coming round a curve...

“Sometimes I get this crazy dream where I just take off in my car, but you can travel on ten thousand miles and still stay where you are.” - Harry Chapin, WOLD

The whiteout was becoming a blackout. Snow had been falling hard when we crossed the Missouri River in Omaha and there already looked to be half a foot accumulated in the fields of brittle brown cornstalks and down the strip of Interstate 80. We were not yet to North Platte in the western third of the state and the Buick Skylark had seemed to float on top of low white clouds. I did not feel it settle back to earth until I slowed to about 40 miles per hour, which would have meant Denver was probably another day distant. Driving through the Nebraska sand hills in the deep of a night blizzard required poor judgment but the nearest town was three hours out and there were no lights flickering across the plains to indicate a place to stop and wait out the storm.

“Ya gotta get your cat to stop stalking the back of the seat, Douglas,” I said. “This is hard enough without her screeching distractions.”

“Hey, she’s scared, too. She’s getting it from me.”

“Well, I’m not exactly confident, either.”

“But you are holding it on the road. Keep doing that.”

I was beginning to wonder, though, if we might ever reach Phoenix. Douglas, a high school friend from my hometown, had decided to give Arizona a try as a possible place to find work and start a career, and I was taking another shot at an advanced degree by enrolling in grad school at Arizona State. One term at San Diego State had taught me that sunshine and beaches and palm trees were not conducive to sitting in classrooms and reading literature, but I thought I might try once more to figure out the course of my life with more education.

My real motivation, which I admitted privately, was to live in a state I had fallen in love with during my days of hitchhiking. There were detailed images in my memory that I could not erase of the summer snow on the top of Humphrey’s Peak north of Flagstaff, the Kaibab Plateau and Coconino National Forest reaching out to the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. I was unable to stop thinking about the Painted Desert and the Mogollon Rim and the giant ponderosa pines standing up against the distant desert floor. Arizona was haunting.

Douglas and I ended up as roommates in an apartment just south of campus and furnished the place with a wooden cable spool for a table and a bean bag chair, which we had bought at the Phoenix dog track’s weekend flea market. Saturday beers were only a nickel, too. Our decorating never increased in sophistication, though. We had no money and going to class was not paying the bills. My experience as a DJ on the university radio station up in Michigan had given me the unrealistic notion that I might be able to land a menial job at one of the Phoenix stations. The responses created a litany of rejections that ought to have directed me toward a different career, but I had been seduced by the out cues of network radio newscasters and their romantic reporting from locales like the Khyber Pass and Bangkok and Paris.

The radio station closest to the ASU campus was KTUF-KNIX, an AM-FM operation owned by country singer Buck Owens, late of Bakersfield, California. I listened to them constantly and tried to mimic voice patterns of their jocks. Eventually, I worked up the courage to stick my head in the door and ask about work or internships. Instead, I became a client, or maybe a customer is the right word, of an overnight DJ. He must have seen the desperation in my eyes and the frayed cuffs of my only pair of slacks.

“You’re fishin’ without a pole,” he said.

“What do you mean?”

“You need a tape. Nobody will hire you without a tape.”

“What you are telling me is I can’t get a job without a tape, but I can’t get a tape without a job.”

“Yeah, that’s pretty much it. But I can help if you’ve got $50.”

“How’s that work?”

“I’m off the air at midnight. Be out front here a few minutes ahead of time, and I’ll get you in the studio and we can cut a tape for you.”

The DJ struck me as a leather-sandaled beer keg in a tie-dyed tee shirt, but he had a voice that suggested death coming round a curve. When we had finished, though, I had a relatively professional audition tape that ran about five minutes with me introducing records and reading news copy. I was pleased and the next morning I asked Douglas if I could borrow the Skylark again to drive around the state and apply for jobs.

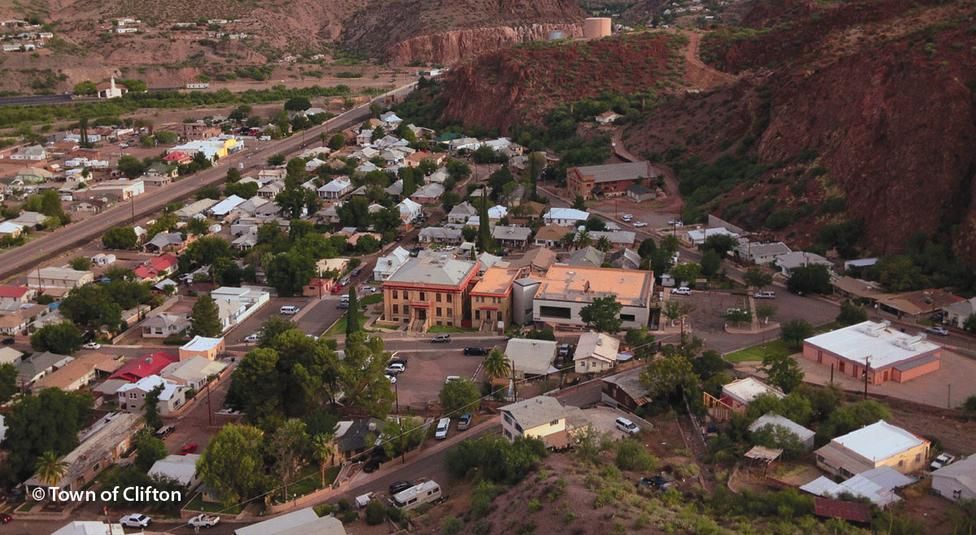

An ad in the back of Broadcasting Magazine indicated that a small daytime station in the mountains along the New Mexico border was looking for announcers. In Safford, I found a pay phone and called the station, which was in Clifton, a small community in a narrow valley that led up to the mountain tops and the town of Morenci where copper was mined. The receptionist urged me to stop by when I got to town and she betrayed an enthusiasm that I had certainly not encountered at any other broadcast outlet I had solicited for work.

I turned northward onto a two-lane that led into low, sere hills, populated with saguaro and long tallus slides that spilled into dry arroyos. There were no signs of human encroachment other than the chip-sealed road, which, disconcertingly, was numbered 666. While I ignored such silliness, I still found myself pressing on the accelerator in a hurry to get to Clifton and the country turned green as I gained altitude. I crossed the Gila River, and the road began a sharper climb and twisted back on itself in a circuitous route toward the San Francisco Mountains along the New Mexico line.

I assumed I missed the city limits sign because I arrived at Clifton without any awareness that I had entered a community. There was an old train depot that housed a Mexican restaurant and I stopped to get directions to the radio station, which I was readily informed I had passed less than a quarter mile down the road. The parking lot was gravel, and the building was cinderblock that had been painted a desert brown. In a large pane of glass, the call letters were arrayed in an arc, “KCUZ-AM, 1490.” I got out of the car and looked in every direction, which set me to wondering who might be around to hear this station broadcast. A few houses were situated on switchbacks up the mountain across the road and a beer and pizza parlor sat not 50 feet from the front door of the studio, a consistent and proximate risk to good health for DJs.

The general manager was a gregarious man in his forties with hair thinning in the front, a smoker’s smile, nervous hands, and the look of someone who thought he ought to be on a golf course, wearing his cardigan sweater in cooler climes.

“Hey, thanks for driving up. My name’s Roy.” He reached out his hand, and I introduced myself. “Are you interested?”

The question put me off balance because no interviewer I had ever spoken to had sounded like they were trying to sell me on their operation.

“Yes, sure, I’m interested.”

“Well, we are going to hire three other announcers and go full time all day.”

“Oh, you’re a daytime-only station?”

“Yes, we protect a clear channel 50 thousand-watter up north.” He made that sound like a heroic task instead of just a frequency assignment from the FCC. “You like sports?”

“Yeah, I guess.”

“Great. We’re gonna need some play-by-play work. Our high school teams are pretty good in football and basketball. Always go to state.”

“Sounds like fun. What about news?”

“Sure, you can do news. We get the wire service, but you can gather local stories, too, on the phone.”

I had listened to KCUZ on the car radio driving up and the only information I acquired had to do with deals on used goods being offered on their “Tradio” program. Listeners called in to offer for sale anything they thought might have value, provided their phone number on air, and address for anyone wanting to purchase. Maybe Roy was intending to upgrade the broadcast hours with actual news.

“So, you’re offering me a job?”

“I am if you are interested. Can we get you onboard?”

“Yeah, that would be great. It’s why I came up from Phoenix.”

“Gotta tell ya, though, I can’t pay much. This is small town radio.”

“How much is not much?”

“A hundred a week.”

I was silent, only partly stunned, which my future employer must have seen on my face because he added they were sure excited about having me join the operation, an emotion I assumed would have been prompted by any applicant walking through the door and willing to work for those wages. Four years of college and a degree to earn $5200 a year, but I had been trying very hard to get my broadcast career started and I had to accept.

“Well, okay. I’ll take it.”

“Great, how soon can you start?” Roy stood and offered his hand.

“I don’t know exactly. Need to go back down to the valley and wrap things up, pack, and get back up here to find a place to live, so maybe a week or so?”

“Sounds great. What shift do you want? Morning, midday, afternoon, or evening?”

“You mean to play music, right?”

“Yes. You’re first hire so you get to choose.”

“I guess I’ll do the afternoons.”

“Outstanding. I will put you on the schedule to launch your show next week.”

My show? The term sounded hilarious. I did not imagine having a show. Was I supposed to have a personality and be entertaining? Maybe I could handle delivering the time and temperature and spinning a record on a turntable, but I was not going to be anyone’s idea of entertainment. Even if I could offer something more than a monotone, my new employer at KCUZ radio was not paying enough to get much more than a button presser. My first paycheck for two weeks was a total of $176.43, which, surprisingly, left money in my pocket. I shared an apartment with one of the other new hires, Thom, and we both paid $40 in rent; I had no car payment, and my small college loan was being paid back at $34.97 a month. A chance existed that I might be able to give myself at least a modest financial launch in Greenlee County, Arizona.

The station had a common failure for the early 70s, though. On air, we simply did not represent the demographics of our audience, which had a large Hispanic population. We were four white boys, Jim, Thom, Steve, and Tim, and not one of us was fluent in Spanish. In fact, we could not even pronounce Spanish names, and I embarrassed myself the first time I had to report a story on the air that referenced Fort Huachuca (Wah-choo-kuh). I called it Fort Hoo-cha-cha. Martinez became Martin-ezz when it emerged from my mouth. I suspected much of our audience found us far more offensive than we were entertaining.

The job was, however, enjoyable, and helped me define my ambitions and sharpen my neophyte skills. I constantly recorded my time on the air reading the news or making comments between records and listened to those tapes to grow comfortable with the sound of my voice, improve my intonations, and envision next steps as a broadcaster. Each week on Thursday, when the newest copy of Broadcasting Magazine, the industry’s trade journal, arrived in the mail, I was waiting in the lobby at the receptionist’s desk. Help wanted ads were listed in the last pages; nobody read that publication from front to rear. The job openings made me wonder if I was destined to spend my career living right on the bubble of the poverty line.

“Wanted, DJ, first phone, (most advanced FCC license), must be able to read and gather news, edit tape, handle commercial production, write ad copy, host four-hour on-air morning drive shift, some sales, occasional sports play-by-play, represent station at community events and remote broadcasts. $131.50 a week and no beginners please.”

The front of the glossy publication tended to get my attention almost as much as the help wanted ads. It was often covered with a big ad for KPRC-TV in Houston. Calling itself the top NBC affiliate in the country, the station’s legendary news director Ray Miller was usually the focus of the promotion and was given credit for leading a news operation that was without peer in the industry. Miller was a journalistic purist and did not even allow his boss, the station’s general manager, to enter the newsroom for fear there might be a mistaken impression he had some influence over stories that were covered by reporters and producers.

“I plan on working there someday.” I tapped the front of the magazine just as Thom walked up to check his mail.

“Yeah, sure, buddy,” he said. “That’s a hell of a long way from KCUZ and I ain’t just talking about the miles.”

“I know. But it doesn’t seem completely impossible.”

“Maybe not impossible,” he said. “Just a bit unrealistic.”

“I disagree, and I’ll send you a postcard when I start my new job there, whenever that is and wherever you’ll be.”

“I hope to have my own radio station, eventually, with a tower on top of Picacho Peak so that I can reach both the Phoenix and Tucson markets and get stinking rich off of both of them.”

“And I’m the unrealistic one?”

Our little team of DJs had only been on the air for months when prices for copper ore plummeted and the Phelps Dodge mine laid off workers to cut back on production. The consequences of that economic development were that fewer people went to restaurants or bought from local stores and those businesses were no longer able to afford advertising on our radio station. We were not exactly a leading economic indicator because our advertising rates were already so inexpensive that we joked frequently we did not need a rate card and told potential advertisers we only cost “a dollar a holler.” Unfortunately, even that was too pricey as the mine slowed output.

Roy let the four of us go before we’d even had time to contemplate what was next. My strongest reaction to the news of getting fired was that I was going to dearly miss the cheese enchiladas with onions that were the specialty of the restaurant in the old train station. Sharing an apartment, Thom and I had become friends, and we had decided to focus our futures on the idea of just screwing off for a bit. He owned a 1964 Ford Falcon, which was a bastardized version of a pickup truck and a compact car, and we decided to drive it to Florida and haunt the beaches for Spring Break. Thom thought his thick blonde hair, big cow eyes, and ever-ready quips would go over well with college girls down from the Midwest, even though he had never met one or attended any institution of higher learning. He invited his buddy Earl to join us, who was also an unemployed Arizona DJ, and we would mark a route on a Rand McNally map to take us across the Southwest, through Texas and Louisiana, down along the southern edge of Dixie, and into Florida.

The Falcon only had room for two in the cab and we put a lawn chair and an ice chest in the truck’s bed for the third passenger. Earl started the trip back there with our packs and luggage. Handsome with a sharp jawline, big white teeth, curly dark hair, and happy eyes, Earl enjoyed the attention from girls in passing vehicles, and did not want to move up front when it came his turn to get out of the wind and desert sun. Thom took us out of the way to the south and showed us his hometown of Bisbee, another historic copper mining settlement not far from Tombstone and close to the Mexican border. After a quick tour, we turned back north and picked up the Interstate near Lordsburg to eat up eastbound miles for Florida.

I have always felt this adventure in my early twenties is when I became a writer. Even in my youth, I scribbled stories on Big Chief pads and imagined reading them into a CBS microphone, sometimes almost hypnotizing myself with the rhythm of words. I remembered conversations I heard and even though I did not know what they were always about, or the definitions of terms used, the tone and the language seemed frozen into my brain. Consequently, when it came my time to sit in the back of the Falcon, passing through the Southwest, I took out a pad and started writing, pressing the pages flat as they fluttered in the wind off the road.

Crossing Southern New Mexico, a sand-specked storm blew hard against the little truck and Earl was forced to fold the lawn chair and curl up on the bed floor until we were able to pull over and wait out the blow. We later crossed into Texas by passing in front of the Organ Mountains and the Franklins as the road eventually curled along the north bank of Rio Grande. Brightly painted adobes leaned against hillsides south of the river, which bent away from our route of travel as we went eastward to the Chihuahua Desert. Texas expanded in front of us and seemed comfortingly familiar to me even though I had only made a single trip across the Panhandle on my motorcycle. The ocotillo and cholla and mesquite scattered against the ragged horizons and broad mesas mysteriously felt like home.

We entered Louisiana a few days later after driving the 900 Interstate miles spanning Texas. Thom wanted to get to Florida for the busiest week of spring break, but we had all agreed that we ought to stop and apply for radio jobs if we came to a town that looked attractive. Following the Red River, we ended up passing under blossoming magnolia trees and greening Spanish Moss, which led us into Natchitoches. The business district was spread upon a tall levee above the river, and we grabbed a newspaper and went down concrete steps to sit by the languid water and look at the help wanted ads.

“Hey!” Earl punched the back of the newspaper. “There’s an ad in here for help wanted for radio announcers.”

“Yeah, man, sure,” Thom said. “I believe ya.”

“I’m not kidding. Look.”

Earl passed the paper to us, and we read the text in a state of amazement. Thom looked at the phone number and we went back up the steps to find a phone booth and dial the station. Instead, we walked right past the office and saw the call letters on the door. In the lobby, we told the receptionist why we had stopped, and she brought us back to meet the station manager.

“Well, ain’t this my lucky ol’ day,” he said. “Three of my boys walk out and three new ones walk in a few days later.”

Shaking our hands, he appeared to look us over as though we were victims of some tragedy. I cannot recall his name, but he was starched up and buttoned down and his shoes shone like a Wall Street lawyer, except he was in rural Louisiana.

“Our good luck, too,” Thom explained. “We all worked for the same station out in Arizona and lost our jobs at the same time when the copper mines started slowing production. The station lost business.”

“Sorry to hear that,” he said. “What brings you to our little corner of Eden?”

“We are traveling across the country looking for jobs,” I said. “Checking out possibilities in places we like. Your town seems pretty, and there’s a university, and we saw your ad. Pretty simple.”

“You got tapes?”

“Sure do.” We handed him our reels and he read our names on the labels. “I’ve got a lunch meeting, but why don’t y’all give me until three and I can listen to your work. Come back by then?”

“Yes, that’s great. We’ll see you then.”

We were still astounded by our good fortune. How many stations would have three openings at the same time? There was a decent chance we might be able to work together, share rent, and get our careers rolling by offering mutual support and criticisms, and learning at the same station. We bought catfish sandwiches and cold drinks and returned to the bench by the river and contemplated our futures. Thom wondered if the college had a drama department; he planned to enroll for a few classes. Earl was looking through the paper trying to find out information on sports teams and how complicated it might be to make a weekend trip to New Orleans. I was focused on the possibility that the station ought to be able to pay us considerably more than we had been earning in Clifton.

Our time and emotion were not well spent. The station manager motioned us into his office when we arrived precisely at 3 p.m. and invited us to sit. I considered that a positive sign.

“You fellas know anything about automation?” he asked.

“Not exactly,” I said. “What do you mean?”

“They’ve got this new machine that can load 8-track tapes and play them on the air for your station. You just pick the music and program in your commercials and news.”

“No dee jays? Any kind of announcers?” Thom asked.

“They say you can record local mentions to play between songs, if you want, but, hell, people listen to the radio to hear music.” He spread his arms and put his palms upwards.

“Sounds like expensive technology,” I said.

“Well, they’re doing these deals now where you can finance. They make it doable, anyway, for little stations like mine. You know, a lot of our costs are people related.”

“Sure, sure.” Earl mostly mumbled. He was already thinking again about Florida. The station manager got up and walked to the door and handed us our tapes as we followed him out.

“Thanks for coming by. I sure do appreciate it. Good luck.”

“Gotta get better,” I said. “Gotta get better.”

This was a new form of rejection I had never experienced. Delivering a “no thanks” for an answer to a job applicant had become an art form so subtle you hardly knew you were being turned away. The letdown was even more profound because we were all in our twenties and had just been told we were second choices to a machine. Carousels of 8-track tapes would spin and select songs that had been programmed for play. Human involvement was minimized. What the hell was I doing with my life?

The three of us did not talk about what had just happened. We walked down the street and got in the Falcon. I jumped in back and sat on the folding chair. Our plans had been to stop in New Orleans, but we decided to rush on to Florida and by late that afternoon we were rolling along Gulf Coast highways and squinting at the sugary white sands spread across the shorelines.

Sunlight and great waters will cure most disappointments and I had the idea that I ought to move south to a beach town and find whatever work might be available while I dedicated my free hours to writing a novel that would enchant every American soul. I could always go back to graduate school, and maybe end up in a disaffected small college town where I might lecture about literature and wondrous authors, or maybe go to New York City and rent a cold water flat and bang away on a manual typewriter until I found a publisher.

Forty-five years later, I still chase runaway dreams.