Born Between Two Cupboards

"I was naïve and knew nothing of hurricanes but thought I had been clever by evading the evacuation order. In a phone booth in front of the restaurant, I called Associated Press Radio Network in Washington and told them I was on the island and had refused to be evacuated."

“You're only as young as the last time you changed your mind.” - Timothy Leary

Radio was not a way to make a living. In college, I had been told that to learn to write fast and effectively for broadcast, the best approach was to start in radio news. The idea was that before advancing to television journalism, you ought to polish up your skills. I suppose I accepted what I was taught but after seeing TV reporters in local news, I realized my university professors were more than a bit out of touch with the industry they were teaching. I did not care. My goal was to become a novelist, and I needed to make a living while improving my writing. If TV presented an opportunity, I would be happy but it was not my primary ambition.

Like every young reporter, I was looking for my first big story. I wanted a break early in my career. I was not lucky, though, like Dan Rather, who got discovered by CBS News while reporting on Hurricane Carla in Houston. My moment came in the form of an outsized bird terrorizing the Texas-Mexico border on New Year’s Eve. When I got the initial call into our radio newsroom from a listener, I assumed it was a hangover tale prompted by too much celebratory mescal. A police officer I had previously met, though, sounded almost in breathless shock as he described a giant creature. He offered details of it flying over the car he was driving while on patrol with his partner.

“I’m telling you,” he said. “This bird’s wingspan was twice the width of our cruiser. There’s no bird down here, or anywhere else that I know of, that big, and you can talk to my colleague, if you don’t believe me. We stopped and got out to look at it but then it saw us and turned back, flying right at us. We got in the car and got the hell out of there.”

I figured they were tired cops rolling up and down the border highways while drunks were out celebrating and the officers just got weary-eyed. They both told the same story, though, which sounded like an episode of The Twilight Zone. I ran a clip of my interview with the policemen during my morning broadcast on New Year’s Day, and the call-in lines at the station lit up with people insisting they had seen the giant bird. An equal number wanted to just make fun of me and the cops. The next day, though, a newspaper story claimed that a Brownsville man told police that his trailer was shaking in the middle of the night and when he went outdoors he looked up and saw a giant bird “taller than a man,” which had swooped down and tried to grab him with “huge claws.”

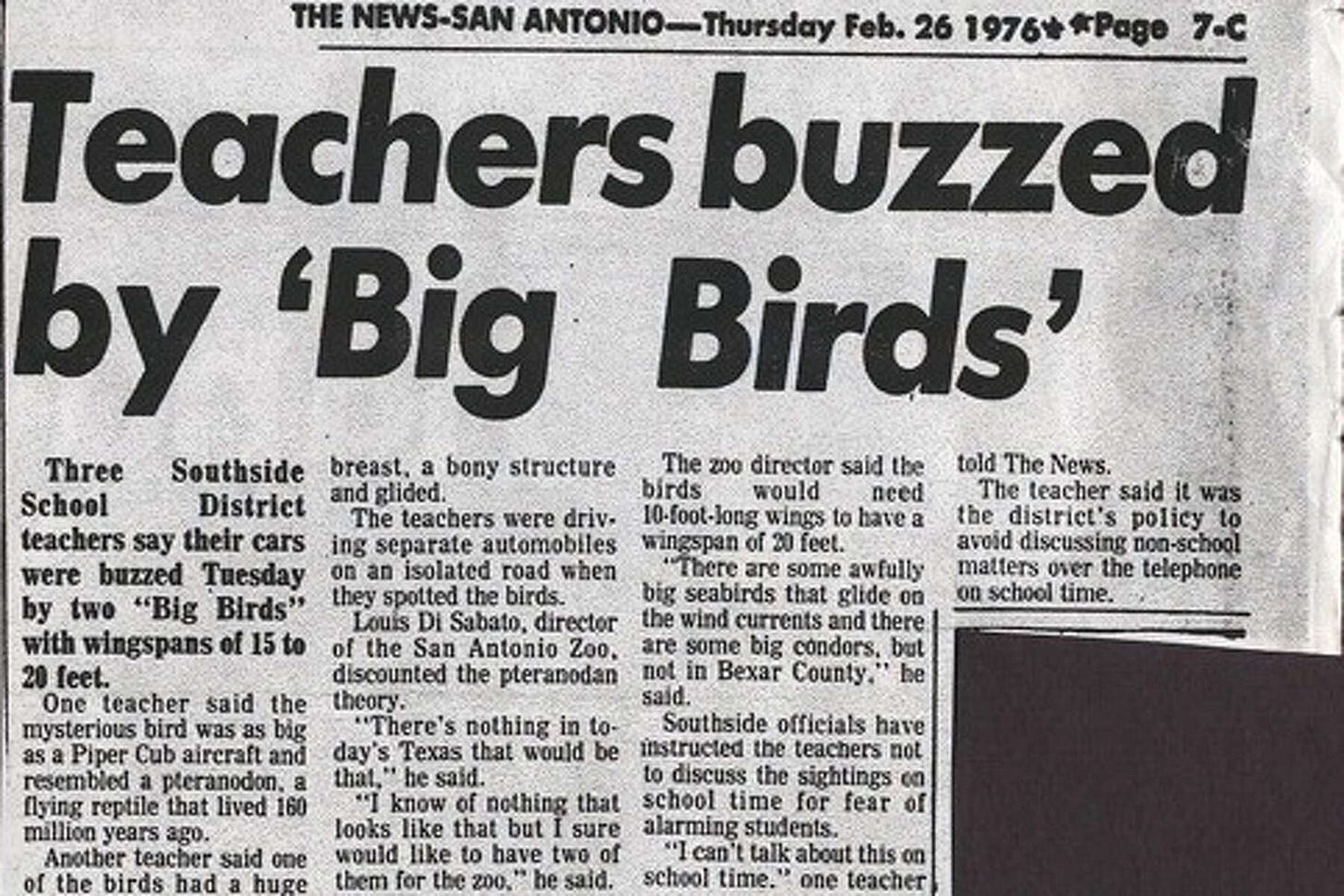

The headlines kept coming and I continued doing interviews for broadcast. One paper used huge block letters at the top of the front page that said, “Horrible-Faced, Big-Eyed Bird Described by Brownsville Man,” and another valley publication said, “Encounter with Big Brown Bird Scary Experience.” An agricultural worker in an orange grove said he had been walking between tree rows and suddenly a creature flew at him out of the sky and grabbed his back with talons bigger than human fingers. Emergency room doctors confirmed they had to patch up his shredded skin, and a picture of bloody furrows in his back ended up in a local paper.

Sightings ranged from Brownsville to San Antonio and up the Rio Grande to Eagle Pass. Two teenaged girls said they screamed so loudly when confronted by the creature that it flew away but their parents found giant three-clawed prints on the ground. A second Brownsville man said the big bird tried to pick him up and fly away with him as prey and he showed investigators a feather that was about three feet long.

The story refused to die. More witnesses claimed to have seen the great mysterious bird. Meanwhile, our phone consistently rang with calls from journalists all over the world after the Associated Press sent a dispatch across the wire. Eventually, I was almost convinced I had seen the feathered freak buzz a donut shop during my dark morning motorcycle commute to sign on radio station KRIO, 5000 red hot AM watts serving the Rio Grande Valley of Texas and the Mexican border.

The nature of the story went against the station manager’s philosophy regarding news. Charlie was determined to ignore the many and manifest social ills of the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas and keep his audience happy and entertained, not scared of big birds or complex issues. Not long before the mythical bird had spread its wings over the big river, a national news magazine had sent reporters to the border region and had published a cover story under a blaring headline, “The Rio Grande Valley of Texas: America’s Third World.” The narrative said we had the lowest literacy rate in the U.S., the highest incidence of intestinal parasites, which was a consequence of the greatest concentration of outdoor privies, lowest average annual income, worst rate of child mortality, and the smallest percentage of population with high school and college diplomas in the entire country.

Charlie did not care, though. Portraying the valley as troubled would be bad for business and that meant less money spent on advertising and fewer cigars for him to chew on while he interviewed leggy beauties to be his sales executives. My first day on the job, he explained what he considered acceptable information for broadcast.

“All right.” He took the wet, unlit cigar out of his mouth, spun it around for examination, and began a brief journalistic lecture. “We’ve got a good congressman and mayor down here, and they pretty much run things. Leave ‘em alone. I don’t want any poly-tics on my air. Ribbon cuttings, only. Then get ya some car crashes, stabbings, robberies, drug arrests, that kind of thing from the cops. I don’t mind that on the air. But I don’t need any big exposes or any of that crap scaring my advertisers. You got me?”

I had him, and immediately wondered how I had ended up in a frighteningly precarious position such a long way from home. I did not say anything, just blinked my eyes, I think, though I ought to have expressed some enthusiasm for employment.

“You taking the job?” Charlie asked.

“Uh, yes, of course. But what’s the pay? You never said.”

“I’ll pay you $160 dollars a week and you can rent the cottage for $160 a month. I’ll need you to sign on in the morning at 5:00 a.m., do the news every half hour, play some records and keep my cart machine running with commercials, get the weather on the air twice an hour, and then you can do whatever you want from 10 o’clock until 3 p.m. but I want you back here in the afternoon to do it all over again until 630.”

“That’s not a cottage,” I said.

“You want the cottage and the job, or not? I got work to do.”

“Yes, sir. I’m here. We came a long way from Michigan. I’ll start tomorrow.”

The cottage was more accurately described as a portable housing unit set on concrete piers directly below the AM radio towers. There were some orange trees nearby but nothing that might be considered a “grove.” Carpeting inside our newlywed’s home was the kind of cheap green fake turf that is used as grass on miniature golf courses. We tried not to laugh every time we walked through the front door. Banana palms grew tall enough near the narrow windows to obscure most of the constant tropical sunlight.

The radio station served more than two dozen communities in the sub-tropical region of Texas known as the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Small border towns had grown up along the northern side of the big river and they straddled a highway that almost paralleled the Mexican frontier as it reached toward the Gulf of Mexico near Brownsville. KRIO’s directional signal pulsed up and down the Rio Grande for hundreds of miles and gave the AM broadcaster a bit of historical market dominance.

Our program director, TK, was always looking to press his competitive advantage, though, and the story of “Big Bird” had set him to scheming. Soft-spoken and slender, he loved working at the radio station and conveyed a passion for the industry that escaped me. Nothing bothered him, and he programmed the station with disco and pop chart songs in the mid-70s that had more potential to gain audiences in Chicago and Detroit than in Donna and Edcouch, little towns along the river. TK’s musical insight, though, turned out to be very astute and he consistently picked gold and platinum records to play in advance of their national success. His office was lined with framed gold records from recording studios whose artists he had helped to make famous.

But I did not think that meant his idea was exactly brilliant when he told me he wanted to press a 45-rpm recording about the Big Bird.

“I’m serious,” TK said. “Let’s do one of those flying saucer type interview records. We’ll create a character to interview the Big Bird and his answers will be short clips from current hits. Maybe the B side will be the story of the Big Bird that you write.”

“That all sounds perfectly stupid, TK.”

It was, but it worked. The “Legend of Big Bird” remained number one on the KRIO playlist for almost four months. Charlie had taken the recordings we made in the studio to Nashville and had several thousand 45s pressed and shipped back to the valley. TK and I guessed that maybe 20,000 were sold but we never knew because any cash went to Charlie and the radio station, or maybe just Charlie.

Wages stayed low and profits remained high at KRIO. No one ever talked about having received a raise in their pay, but I thought I was due for a nice bump after about 18 months. The Big Bird story had driven our ratings to the sky and my journalism had won the station its first awards for reporting from the Associated Press. I petitioned Charlie for an increase in pay and he assented without argument and told me there would be a “little something extra” for me in the next pay cycle. I ought to have asked about how much of an increase he was going to offer because his description was painfully precise. When I opened my check envelope, I looked at the numbers and did not recognize a change. Fortunately, Charlie had written out the math for me in red pencil on the back of the stub for the pay voucher.

“.05 per hour x 40 hours = $2.00 per week x 52 weeks per year = $104.00.”

“A little something extra” was the perfect descriptive. Initially, I laughed, thinking he was kidding and would give me a decent check when I walked into his office to complain. Lord, was I wrong.

“Are you serious, Charlie?” The boss man did not look up from whatever he was reading. “This raise on my check? A nickel an hour? You’re just messing with me, right?”

“I thought you wanted a raise.” He looked up so I no longer was staring at the shining top of his bald head.

“I did. Not an insult.”

“You’re saying you don’t want it, then?”

“I want a real pay raise. You know, one that says my work and the impact I’ve had on revenue and ratings is appreciated. That kind of a raise.”

“That’s what I gave you.”

“No, you didn’t.” I found myself looking out the window at the orange trees and the sunshine and wished to glory hell I was not in this man’s office. “Tell you what, Charlie. Looks to me like if all you can afford to give me is a nickel an hour increase, the station must be in dire straits and you all must need that nickel worse than I do. Why don’t you go ahead and keep it?”

He shrugged. “Okay. I will.”

Without ever taking the cigar out of his mouth, Charlie went back to whatever he had been reading. My next paycheck returned to $160 a week before deductions, instead of the $162 he had offered. The dreams I had envisioned for using the extra two dollars each week had all been dashed by my intemperate attitude toward my gracious employer. There were cheeseburgers I would never come to know.

A shortage of money was not the only challenge to assimilating into the border culture. Although the river served as an international frontier, residents on both sides viewed it as a unifying geographical feature and not a dividing line. Families have lived for centuries crossing the muddy water for commerce and culture and have not considered there were great differences between their two nations. In fact, the prevailing view among South Texans has been that the border region is almost a unique nation unto itself.

The radio station broadcasts, though, were all in English, but it was a second language for much of our audience; especially younger listeners. They often called to request the playing of a favorite song but struggled to find the correct verbs to make their wishes understood. Frequently, a tiny voice might ask us to “put” a song for them, instead of playing one. I heard this awkward locution frequently enough that I eventually stopped calling our phone tree the “hit lines” and began referring to it as the “Rockin’ Rio Put Lines.”

Only I thought that was funny, though.

A few of our listeners were probably uncertain of the lyrics they were hearing played over the air. Song verses are often difficult to understand in your native language. I constantly failed to understand what was being requested when I took listener inquiries from young callers trying to master two languages. I usually recorded the calls to my request line and played them back as intros to the songs, which was an audience affirmation that they had some control over our broadcasts.

A number one song on Billboard tended to be frequently requested and could be entertaining for more than its music and lyrics. One morning as I was recording conversations to run as intros, a squeaky, breaking voice barely registered in my earpiece.

“Hello. Rockin’ Rio hit line.” A long pause ensued before the tinkly speaker tried to communicate.

“Mister? Mister? Can you ‘put’ a song for me?” Sounded to me like a little boy barely over five or six years of age.

“Sure, I’d be happy to ‘put’ a song for you. What would you like to hear?”

“Can you put that song by that Mary?” Momentarily, I did not know what I was being asked.

“Oh, you mean the hit song by Mary McGregor?” She had been number one for several weeks with a ballad called, “Torn Between Two Lovers.”

“Yeah, her mister. Can you put that song ‘Born Between Two Cupboards?”

I am not sure if the coffee that came out of my nose was heard over the air, but I do know I needed to wipe a lot of it off the control board when I hung up. I was, however, able to stifle my laughter until I closed the microphone. First, though, I had to introduce the record.

“Direct from our Rockin’ Rio Put Lines, by request, this is Mary McGregor, and Born Between Two Cupboards.”

I sang reimagined lyrics to myself as the record spun. “Born between two cupboards, feelin’ like a fool…..” Who wouldn’t, really?

We might still be down there were it not for a hurricane. Neither of us had lived through a tropical cyclone and did not know what to expect when the clouds began circling in the Gulf. I watched the weather wires in my little newsroom and called the Coast Guard for interviews and hotels and restaurants down on South Padre Island to ask about their concerns. The Texas Department of Public Safety issued a statement regarding the evacuation of the island as Hurricane Anita hit steering currents that began to guide it toward the mouth of the Rio Grande.

For irrational reasons, I decided my job responsibilities included going to the island as the storm moved toward landfall. I was a one-person news department, though, and had no idea to whom I would report any information I gathered. TK volunteered to work the control board and patch me through to broadcast when I called in with any type of report. Anita’s wind speeds were increasing and had reached more than 100 miles per hour while spinning well offshore. Just as I crossed over the Queen Isabella Causeway and looked out to the darkening wall of clouds across the water, the radio announced that South Padre had been ordered evacuated by the governor.

I turned sharply south to where the jetties stood against the sea and tourists tended to gather on the beach near a popular restaurant. Police were moving through the parking lots and inside of buildings to usher visitors out to their vehicles to get over the high causeway before the winds became more dangerous. I slipped around behind the cinderblock restaurant building and crouched near a small pump house to protect myself from the wind and the law. No one thought there might be a grown adult hiding to stay on the island as the storm surge pushed the tide up over the roads. Who might be that foolish?

I stuck my head around the corner and saw seagulls on the beach with their beaks pointed toward the rising wind and the water pushing far up the beach. When the birds sit down and turn to the wind the storm is on final approach to landfall. I was naïve and knew nothing of hurricanes but thought I had been clever by evading the evacuation order. In a phone booth in front of the restaurant, I called Associated Press Radio Network in Washington and told them I was on the island and had refused to be evacuated. The news desk kept my line open and I filed constant reports from inside the glass and metal box as the water rose up to my knees. I was suddenly afraid, and aware that I had been previously stupid.

Hurricane Anita stalled, however, and sheering high-altitude winds reduced its power, which was probably a saving grace for the person on the phone talking to AP. If the storm had sustained its energy, I might have drowned. Instead, the water receded, and I was back in the radio station in a few hours. Damage throughout the four-county border region was minimal, and the one piece of information I wanted to report had to be dropped onto the cutting room floor. The former Miss America, Anita Bryant, who had been pushing anti-gay rights laws in South Florida’s Dade County, became the brunt of an incisive joke about the hurricane that bore her name. A gay rights activist in McAllen suggested to me in an interview that it was appropriate that Hurricane Anita had turned out to be little more than a “bad blowjob.”

The weak wind blew my life in a new direction, though. A news executive at a television station in Corpus Christi had listened to my hurricane reports for the five hours I had held open the phone line and talked to editors in Washington over the AP Radio Network. He called the switchboard at KRIO and asked for the newsroom and said he had a tip to give the news director. When I answered the phone, he said he had found my hurricane work “courageous” and “riveting,” instead of stupid and reckless. I did not care, however, if he was being disingenuous. He asked me if I had ever thought about working in television. I had, but considered it unlikely I might ever land such work.

“Well, I’ve got an opening here,” he said. “You interested in coming up and doing an on-camera audition for the job?”

Oh, was I ever.