Can a Photo Stop a Bullet?

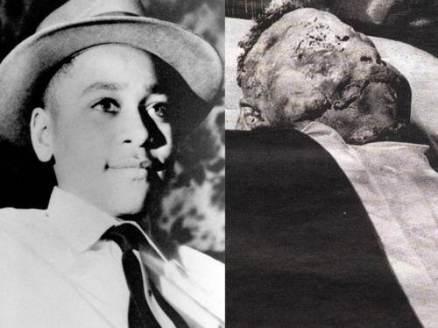

"Let the people see what they did to my boy." -Mamie Till Mobley (mother of the lynched Emmett Till)

NOTE: Once again, I'm breaking my rule over "trigger warnings" and issuing one this week. There are photos herein that are intensely graphic in nature, though all are historic and have been widely covered.

I’ve always loved photography. Whether it’s the thrill of actually taking pictures or just seeing great photos. As a kid, I remember being fascinated by a camera case that contained a couple of Rolleiflex medium format cameras that my dad brought home occasionally. He was in corporate communications and sometimes took pictures for the company newsletter and magazine. It was a giant leather photo bag that I could barely lift as a child. I would sneak the cameras out and pop open the ground glass viewfinders to try to focus on an upside-down world.

For my 8th or 9th birthday, I got a Kodak "Instamatic" camera that used a small film cartridge and flash cubes. I loved getting the square photos back from Fox Photo film-processing stores in all of their muted colors. Trying to capture the image that you want and the experience that you have trying to do so in all of 1/60th or 1/1000th of a second was and is a blast.

Making an emotional impact with an image that you produce is even more thrilling. The perfect baby picture. A portrait that somehow captures a person’s entire personality in a single frame. Action shots from the sports field, a boxing ring, or a basketball court that communicate moments of human struggle that transcend our physical limits. Wildlife and landscape shots that bring the breathtaking beauty of the natural world into our insulated, domestic lives.

And then there is photography that documents news and current events. Some of it seems mundane - the recording of how we live and work and play and raise our families every day. But the most impactful photography is crisis and conflict photography... produced most often by the news photographers and documentarians that cover wars, violence, and all manner of crises in your neighborhood or across the globe. This is no longer the exclusive domain of professionals, paid by newspapers or film producers, (much to the chagrin of paid professionals.) Anyone that has a smartphone has a camera, so that covers most of the people on the planet. Still, pros are usually the ones that go where the action is and they are usually skilled at grabbing those dramatic shots that affect us deeply and sometimes change history.

Covering conflict and even daily news can be physically and mentally challenging. When I worked at a local network-affiliated TV station in the late 80s/early 90s, I often tagged along with the news crews in an engineering/technical support position. I drove and operated the "live trucks," the satellite or microwave antenna trucks that transmitted live reports or edited stories back to the station. It was a time when local news was spending a lot of time and money covering everything from city hall to investigative stories to "spot" news... car wrecks and shootings and the like. I was rolled out one morning to meet a reporter and photographer working a local house fire. It was a lovely home in a stylish neighborhood, and there were early reports of a couple of fatalities... children. I remember parking among the fire trucks, first responders, and other news vehicles. The scene was quieter than usual. The firefighters and police went about their tasks. But the subdued press pack was almost silent, and the look on the gathered neighbor's faces confirmed that indeed, there had been children that perished in the blaze. Even worse, the mother had not been told yet. Word passed around that they were bringing her here, to the still-smoldering scene to tell her.

I was sick to my stomach. How appalling! We were standing around, waiting to photograph a woman being brought to the scene of the most horrific tragedy that she could ever conceivably experience. Still cameras strapped around necks, video cameras resting on shoulders, everyone was waiting to photograph her when she was told that her children were dead. I felt ashamed. Like twisted voyeurs ready to produce some perverted form of catastrophe porn, we waited. A car drove up, and someone helped her out of the car. She walked into the middle of this spectacle as someone explained what had happened and the full weight of this otherworldly scene hit her. She collapsed, screaming, sobbing.

Over her cries, you could hear the shutters whirring.

It was one of those days where you think, 'I can't do this. I cannot be a part of this... exploitation.' That's what it is, isn't it?

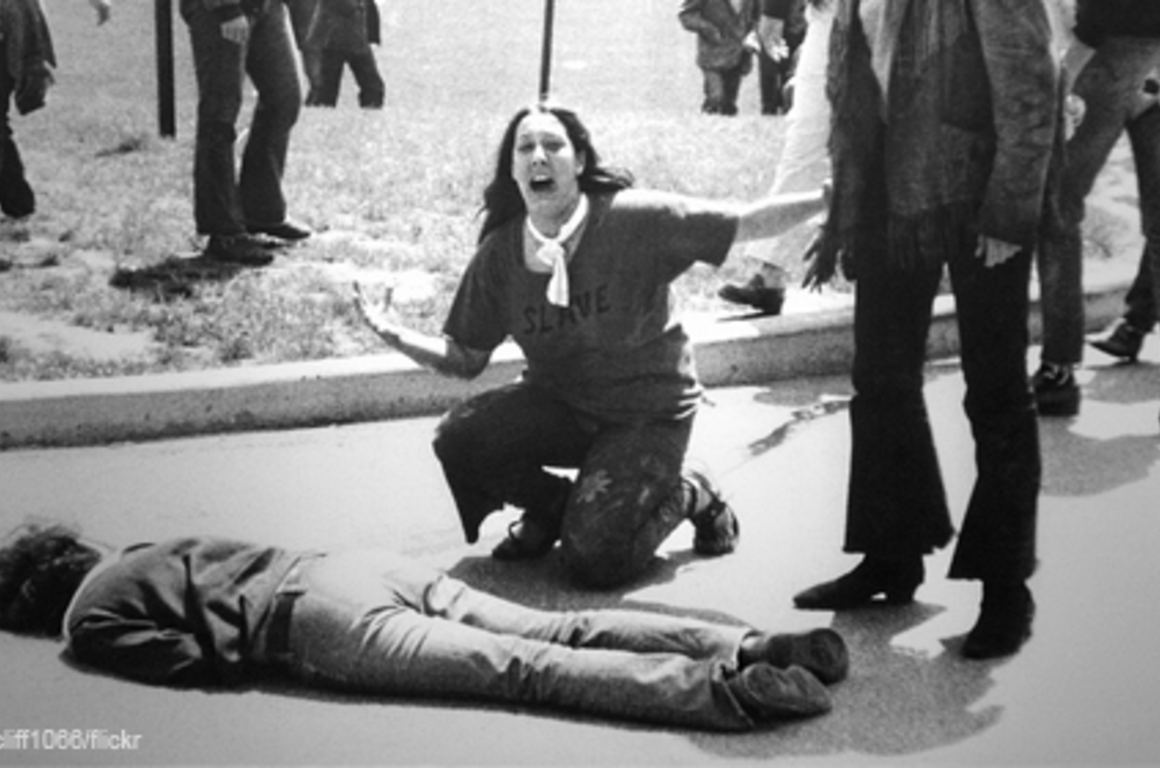

And then I remembered... those famous photos that I'd admired forever. Like the one of Mary Ann Vecchio at Kent State. <above> Someone paused long enough to raise a camera, focus, and opened the shutter to capture that moment in time. Even in that moment of tragedy. It was history. It was a part of the human condition. It was a soul check.

I would not compare a local housefire to some of these historic tragedies, but the grief in the image was certainly equal to the grief I saw that day. Could viewers see this poor soul and feel compassion? Could a photo or video of her that was published put us in her position? Could we, if only for a moment, share completely the humanity of that moment?

I didn't quit, and my colleagues and I saw a lot of tragedy, a lot of excitement, and every now and then, we recorded joyful moments among fellow humans. The emotional impact was always there, and we always tried to take that to the viewer.

"Gee Chris, where are you going with this?"

For years, as the bodies from mass shooting events have been stacking up, I have wondered why we are hesitant about posting photos of the crime scenes, including showing the damaged bodies of the massacred children. No wait, stay with me, here. I have been surprised lately, that this is now an idea that is getting some traction. Several prominent writers have asked this question lately. The New York Times here, the WaPo here, Vanity Fair, here, and even Texas Outlaw Writer James Moore alluded to it here. Many seem to feel, as I have felt for years, that a photo of the ravaged body of a child might just be the catalyst to convince the general public - and even a responsible gun owner or two - that the wholesaling of military-grade weapons has gone too far and that reasonable limitations placed on their sale is fervently needed. If we were made to look upon the shredded remains of a small child, wouldn’t that finally be enough to turn our stomachs and change our minds?

Most of these linked articles above reference the lynching of Emmett Till and the photo of his body lying in an open casket that his mother insisted be published in the press. You’ll recall from your civil rights history reading (uh, no longer allowed in school if someone were to call it "CRT") that Emmett was a young, rambunctious teen who was (falsely) accused of whistling at a white girl in Money, Mississippi. This was in 1955, deep in the Jim Crow south. Some very upset rednecks beat Emmett, shot him, weighed him down, and dumped him in the Tallahatchie River, possibly while he was still alive. (His assailants were unsurprisingly acquitted. ) His recovered body was grotesque. Cut, bruised, shot, his head smashed in, his body swollen and bloated from the drowning.

Mamie Till, Emmett’s mother, channeled her fury. After seeing her son’s body and experiencing the absence of justice for Emmett, she demanded an open casket funeral and invited photographers to document the wretched sight. Only Jet Magazine and The Chicago Defender - publications known and popular in the black community - agreed to print the photo. Due to the sensational nature of the picture, it circulated internationally and became known to white audiences. People were aghast. It didn’t change the hearts and minds of every single racist in Mississippi, but that photo (along with the picture of his Mamie Till grieving over the body) are generally credited with giving the civil rights movement a jump. Notably, it affected the way many whites saw the black experience. It took deniability of racism off of the table and confirmed the degree of cruelty that blacks in the south dealt with. Just like the cell phone footage of George Floyd being murdered while in police custody, the lynching of Emmett Till and the photos of the aftermath confirmed what blacks in America knew all along.

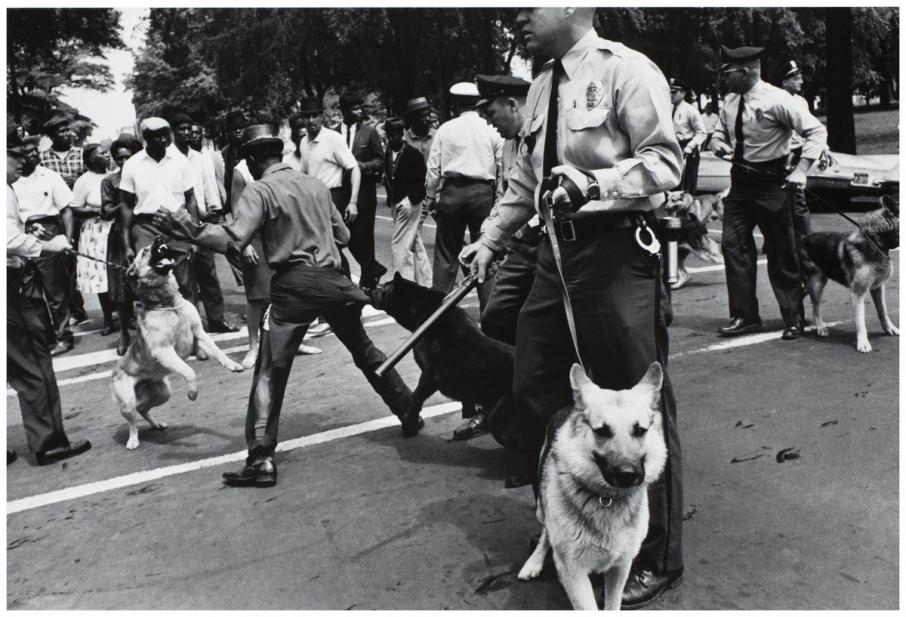

There were other classic photos that moved the movement. Photos (and then news film footage) of the dogs and firehoses being turned on to peaceful protestors, the attacks on the "Freedom Riders," and later the pictures of rage and violence shown to the first black children being integrated into white schools. All of those classic photos put ripples in the American pond. The white majority was forced to look and answer the question, "Is this who we really are as a country? As a society?"

This was, in fact, part of MLK’s "peaceful protest" strategy. If he could keep his marchers and protestors peaceful, the violence that it drew from Southern crackers and racists would be on display for the world to see. News photographers would be on the front lines of that effort. It (mostly) worked. And make no mistake, the marches, the protests, and the attacks were calculated to draw violence upon them, and many Americans were actually shocked.

The press has always had a tenuous relationship with those in power. In the Civil Rights era, southern politicians, white supremacists, and your run-of-the-mill bigots began to threaten and attack members of the press almost as frequently as they did blacks and their allies. Photographers with their cameras around their necks or big film cameras on their shoulders were often easy targets.

Because those photos had power.

Recall the famous picture of Rosa Parks, sitting in the front of the bus, refusing to sit in the back. It happened. Ms. Parks broke the segregationist's law. But she was not the first. Claudette Colvin at 15 years old, was the first Montgomery bus passenger to be arrested for refusing to give up her seat for a white passenger - nine months before Rosa Parks was arrested. Leaders of the civil rights movement were aching to advance the cause.

And that famous photo? Staged.

They selected Rosa Parks to make their point for a reason. Ms. Parks was an active member of the local NAACP chapter. She was elderly, and her sweet face radiated kindness, at least when posed for the camera. So her strategically planned act was restaged for a photographer.

Bingo. It worked. The black community began their famous bus boycott while the NAACP planned lawsuits over Montgomery's discriminatory practices.

The power of photography.

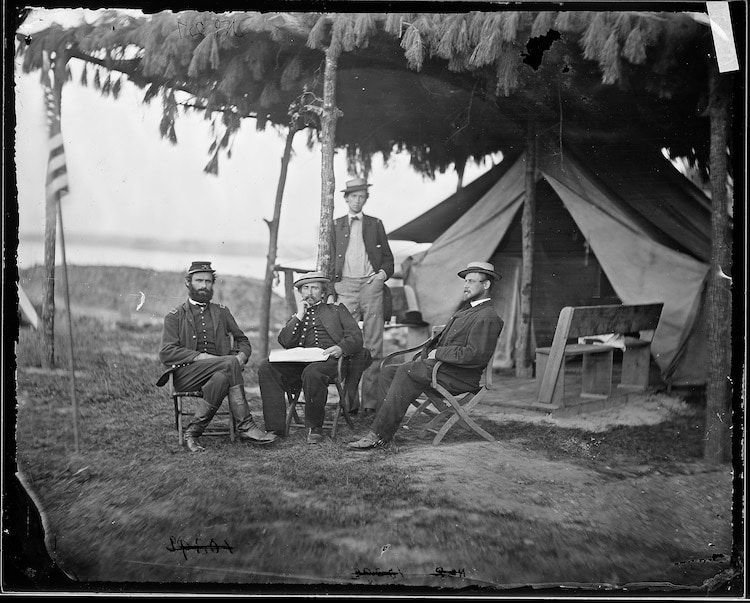

Historically, that power has been known from the start. Photography was barely a novelty when the civil war broke out in the US. It was a crude, chemical process that involved spreading light-sensitive silver crystals in solution onto large glass plates. The plates were placed into those "old-fashioned" view cameras with the accordion-type bellows that focussed an image onto the plate. A photographer would pull away a cap blocking light from passing through the lens and expose that plate to a focussed image. The glass plate was processed in chemicals and then an image would be projected onto light-sensitive paper (and processed in chemicals) to create a "positive" from the glass negative.

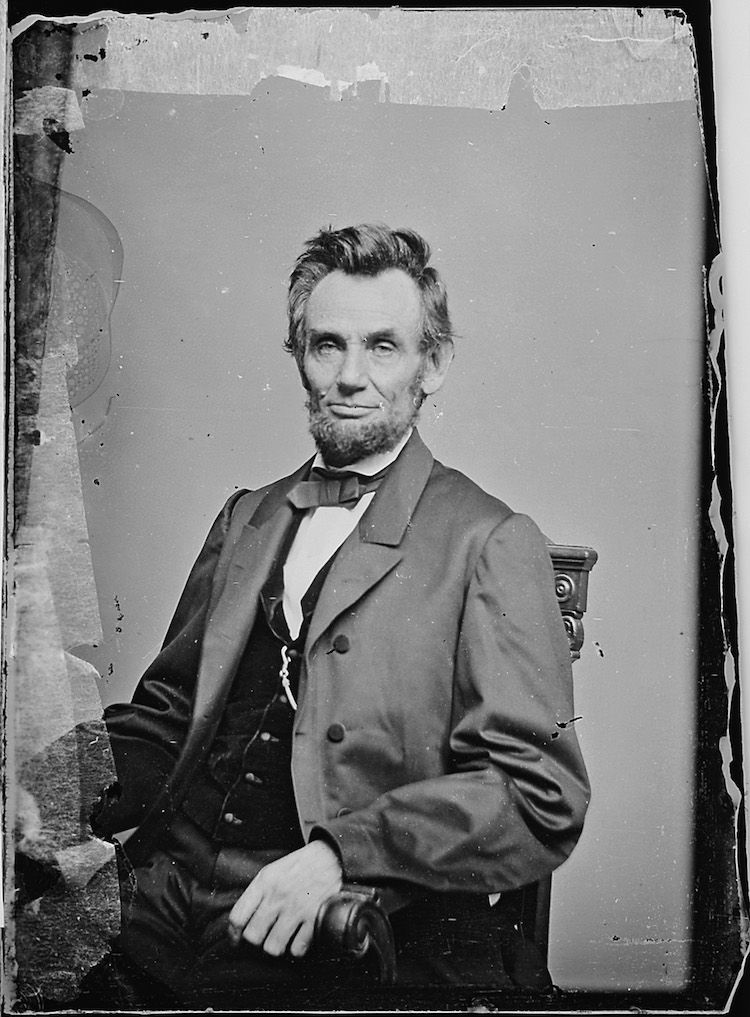

Soldiers, on their way to war, would have portraits made to send home to their loved ones. Sitting proudly in their military uniforms, usually resting their heads against a metal brace so that they wouldn’t move during the long exposure times, they sat stiff straight, rarely smiling (this was a serious business!) And it WAS a business. From the lowliest volunteer private to President Abraham Lincoln, people were marveling at this new art form.

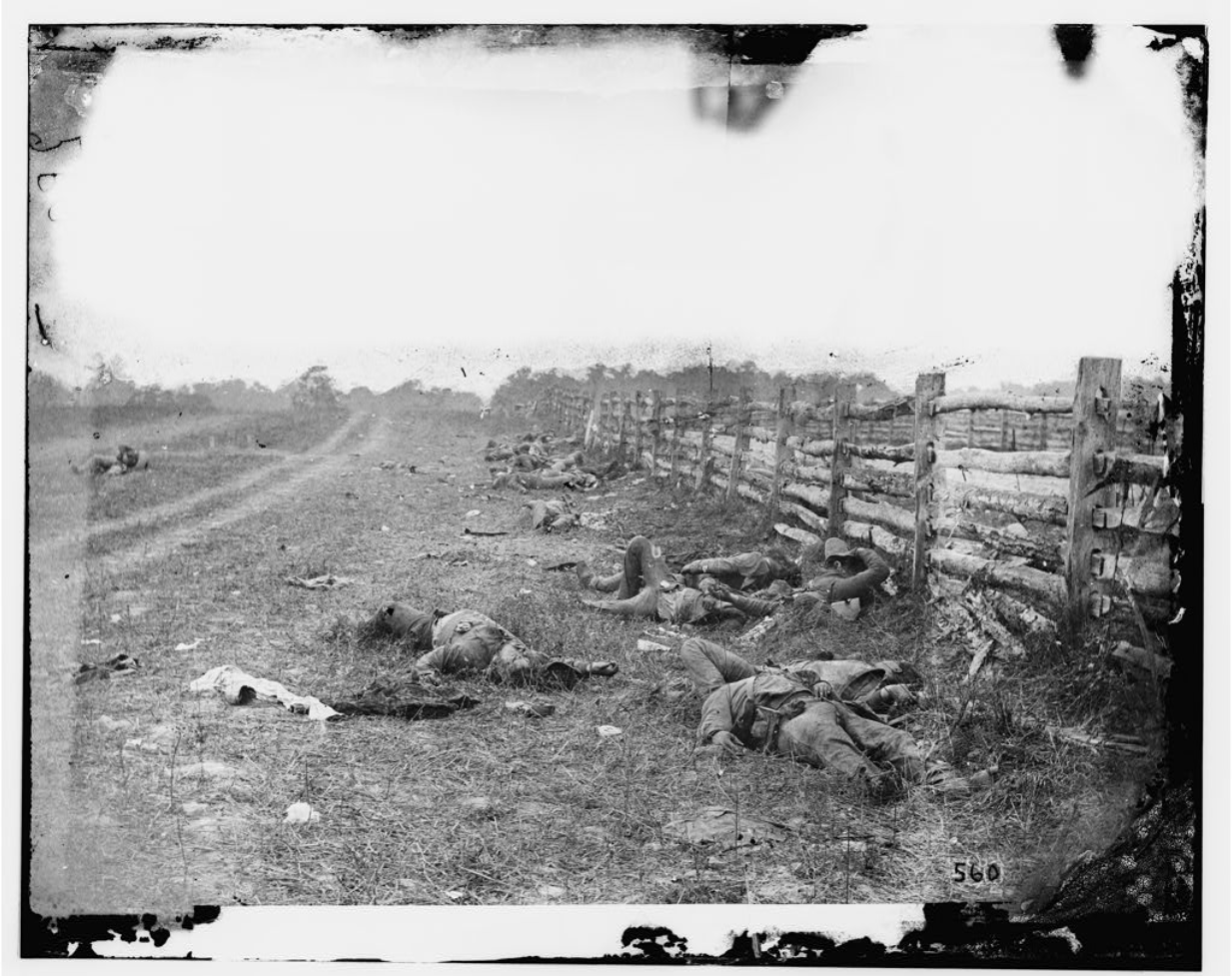

If you’ve ever studied one page of Civil War History, you’ve probably seen the photos taken by Mathew Brady and his associates. Brady started by taking the usual civilian and soldier portraits, but soon he loaded his wagon with the huge cameras and chemicals that he would need to go to where the action was. Readers of newspapers of the era were used to getting first-hand written accounts of the war, often wildly embellished with sensational details meant to make the war seem exciting and dramatically appealing. There were artists and illustrators of the period that would attempt to capture the scenes of war. These illustrations had to rely on the artist's technical ability and very personal interpretations of their witness to war.

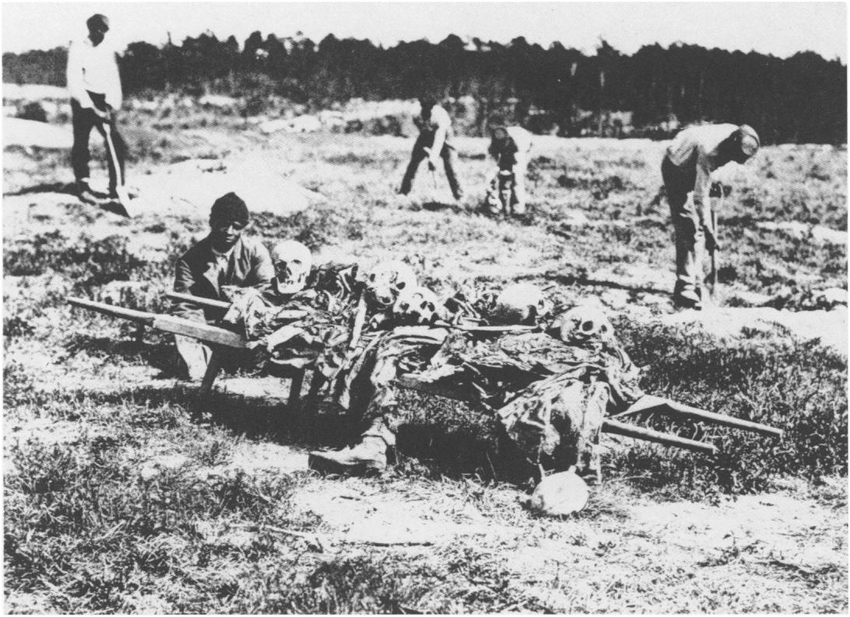

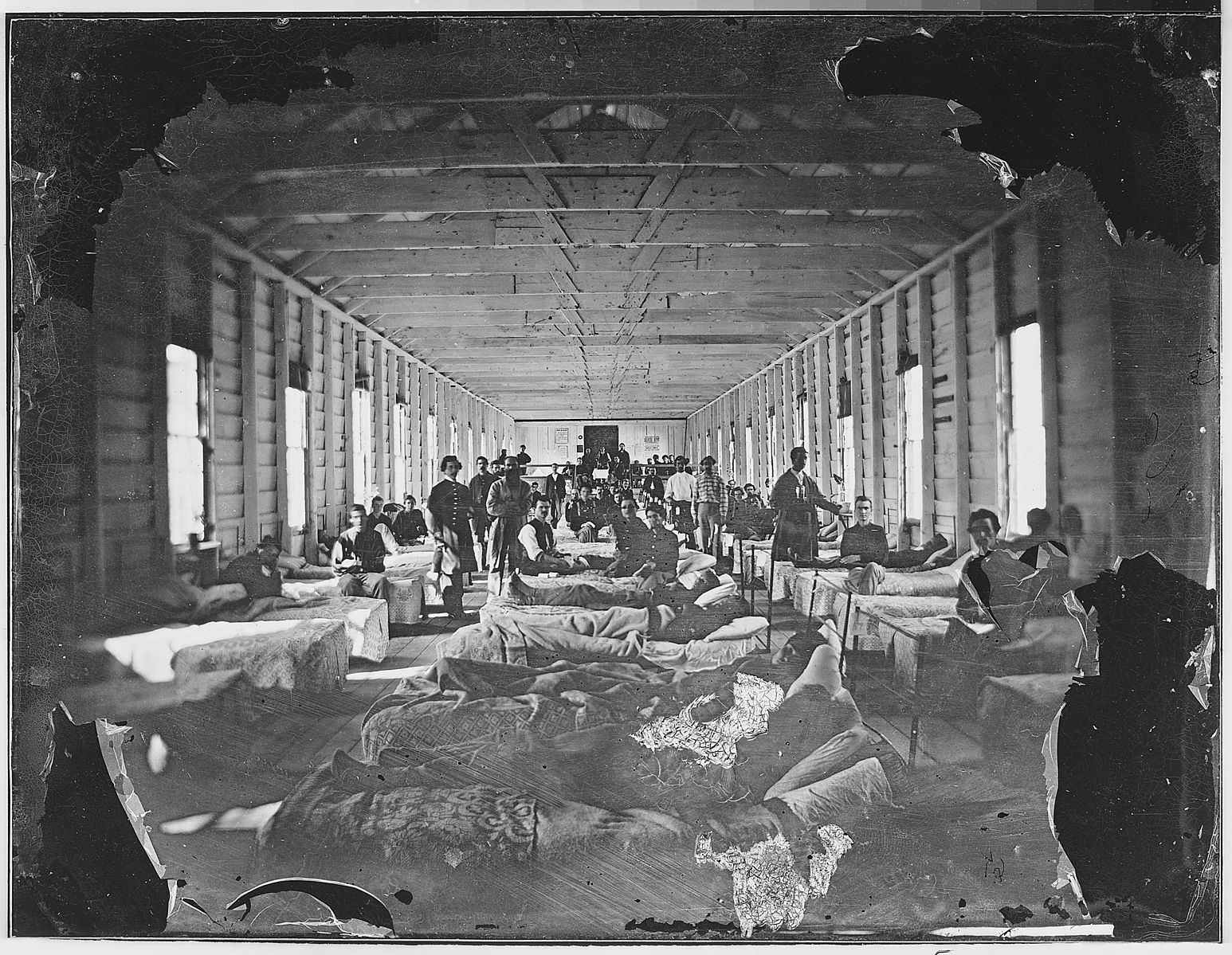

But Mathew Brady brought the real horror home. From the live action of men in battle to the horrific wounds and stacks of the dead in the aftermath. People back home had never seen nor imagined anything like it. All the pre-war propaganda, swagger, posturing, and pretension about the glory of victory was no match for the physically documented and published photos of the carnage of battle. It was terrible enough that the loved ones of soldiers nervously waited for word from the front and read casualty lists that were printed in local newspapers. But to actually SEE the horror of a hospital tent, the limbs and bodies lying and rotting on an open battlefield, and the spectacle (and numbers) of the massive war... it was a shock. All the pre-war, romantic notions of gallantry and honor seemed absurd in the face of this documented horror.

In 1862, shortly after the Battle of Antietam, Brady's gallery hung several photos taken at the battlefield by one of his associates, Alexander Gardner. Titled "The Dead of Antietam," the exhibit drew a huge crowd and the attention of the press. Newspapers and other periodicals still could not reproduce a photo, so Harper's Weekly produced woodcut engravings of 8 of the photos. It was the first time that war dead were photographed. Reporting on the exhibition, the New York Times would report

“If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it.”

It was no longer a matter of easily "selling" the war to boys looking for adventure, filled with notions of excitement and victory. The fight for "state’s rights," (you know the right that we’re talking about) would become a tougher proposition after Mathew Brady's photographs of the shredded bodies of brothers, husbands and fathers traveled to every corner of America.

Though photography and specifically battlefield photography was in its infancy, the photographers already knew the power of their photos. They knew that every picture told a story. Researchers suggest that even at this stage some photos were being staged, bodies were being moved for the sake of composition, narrative, and dramatic effect. Mathew and crew were Union men after all, and whatever they could do to enhance the North's image through their own images, they were willing to try.

Lincoln once joked that he could not have won his election without his fine portraits that were taken by Brady. Conversely, the Civil War photos on display around the North and the hundreds of images made available to the press put enormous pressure on the president to conclude the war and stop the carnage.

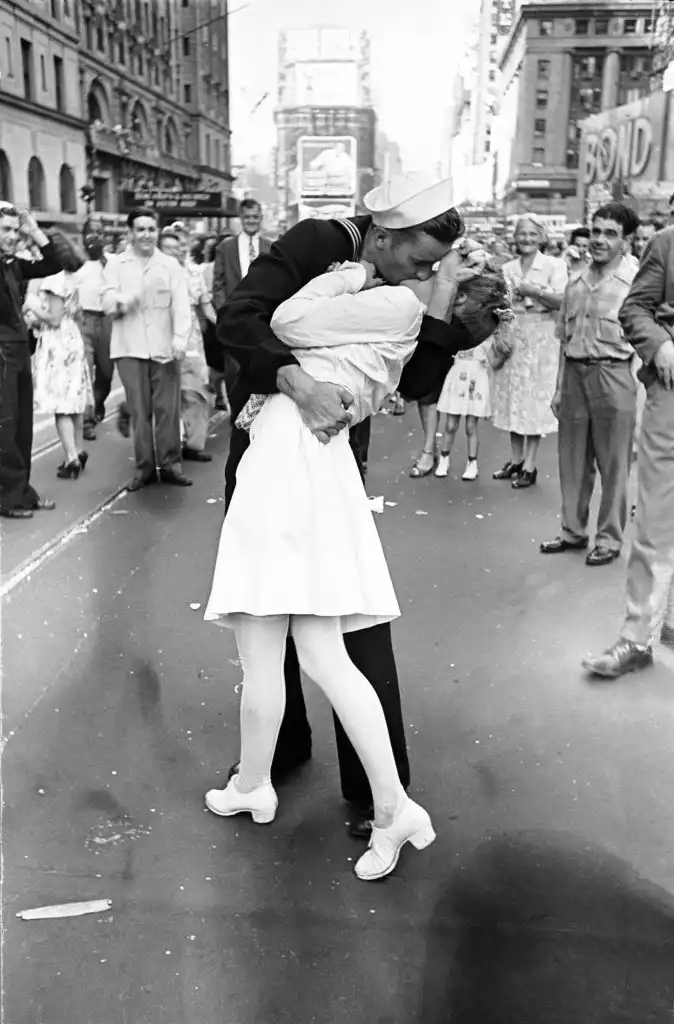

War photography would play an even larger part in future conflicts. In WWI, all press was censored. In WWII however, FDR did not want Americans to get complacent about the war and believed that seeing the suffering of soldiers would boost America's resolve. Correspondents and photographers hitched rides with regiments on the way to the front. Reporters boarded planes that were making highly risky bombing runs over Europe. They camped with army units, sailed aboard navy ships, and flew along on transports and air raids. Once again, the real cost of war was documented and delivered via the daily newspaper to the front stoop of American homes. The press voluntarily (and it was thought to be patriotic) accepted some level of censorship during the war. Troop and material movement, the extent of win/loss records, and even casualty counts were hidden at times from the public. WWII was (generally) supported by a (generally) united country and many of the more grim photos were not released until after the fighting was over. We were fighting the Hun, the fascist Nazis that were trying to take over the world! We were fighting the "Nips" (Japanese) that had attacked Pearl Harbor, our homeland! Most photos showed American power, acts of bravery and courage, and the incredible destruction being unleashed in Europe.

It was pure boosterism. Most of the press corp considered it an act of patriotism and not propaganda to show "our boys" in a favorable or sympathetic light. The War Dept. was fully aware of the power of photography and generally supported wartime coverage. They even worked with Hollywood in producing movies depicting US heroism in order to boost morale and encourage enlistment and war bond sales. The US rallied behind the flag and behind those photos.

The power of photography.

The Korean War was confusing for most people. There were few that understood the reasons for the war, but the country was still full of patriotic fervor from WWII. Men were drafted, fought the North Koreans, (or was it the Chinese?) and came home... or didn’t. Most photography of the era was content to tow the perceived patriotic line. Commies were over there, threatening the world... or something. There is a reason that Korean vets claim that their war is the “forgotten war.”

Then Came Vietnam

Then came Vietnam. Another conflict in SouthEast Asia that kept escalating, and no one was quite sure why (maybe the Commies were still coming for us? One thing was for certain, we weren’t in it to LOSE, we’re ByGodAmericans!) But a counter-culture was brewing. The purpose of these wars seemed ill-defined. What was defined was who would serve and die. A draft was running, and lotteries were held to choose who would be required to fight. Rich kids, and to a certain extent middle-class kids could "defer" their obligation to serve if they were enrolled in college. Others might seek a medical exception - you know - like bone spurs and such. But those with few resources had no way to attend a university. The war would be fought disproportionally by poor and minority draftees.

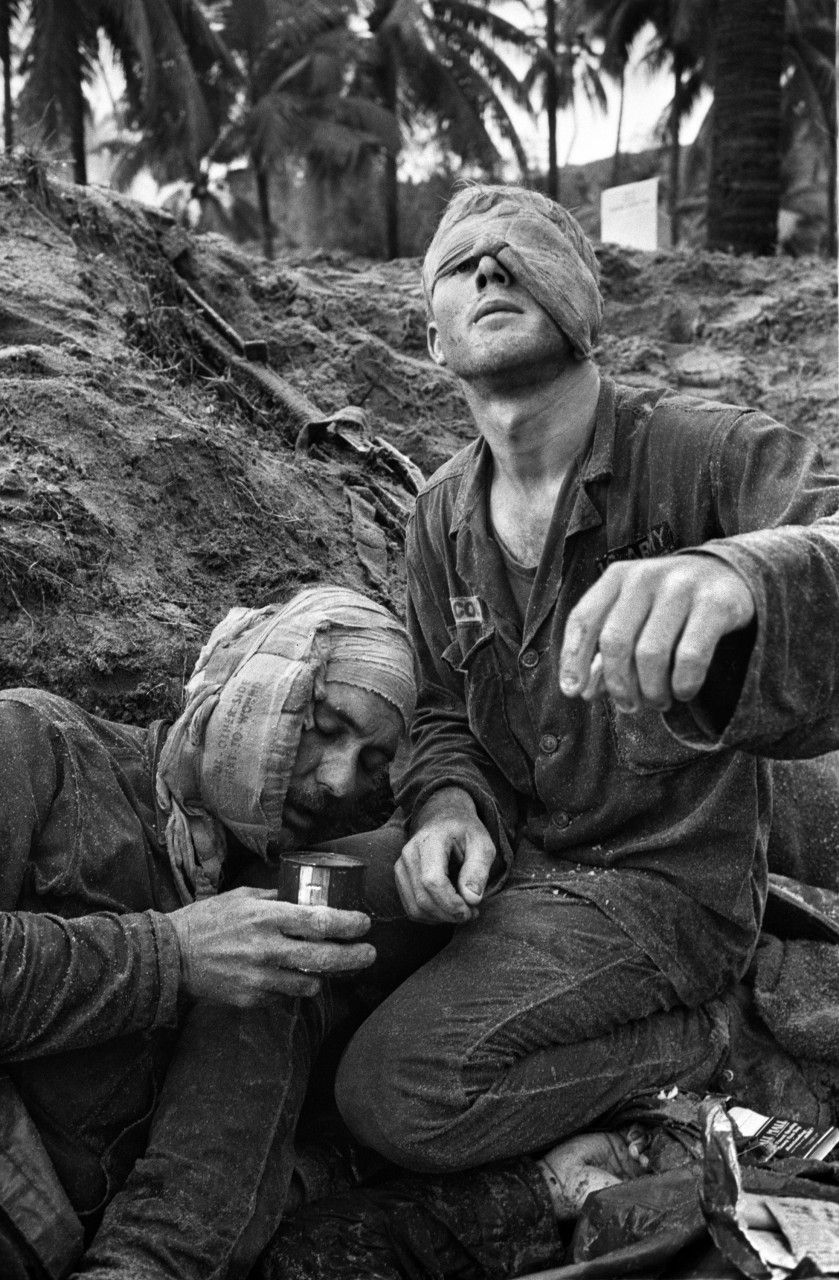

And the photos rolled in. Reporters and photographers were still free to cover the war closeup, choosing to get out in the field and once again, hitch rides on Huey helicopters or in motor convoys.

As the counter-culture and anti-war movement grew, pressure also grew to report more critically on the war. The body bags flown home were increasing in number and the VA hospitals were doing a brisk business. A new generation of reporters was going off into the jungles and sending home photos of what they were seeing. And those photos were disturbing. Women and children caught in the crossfire, if not directly targeted. Villages set on fire. Reporters noted that some of these incidents were premeditated.

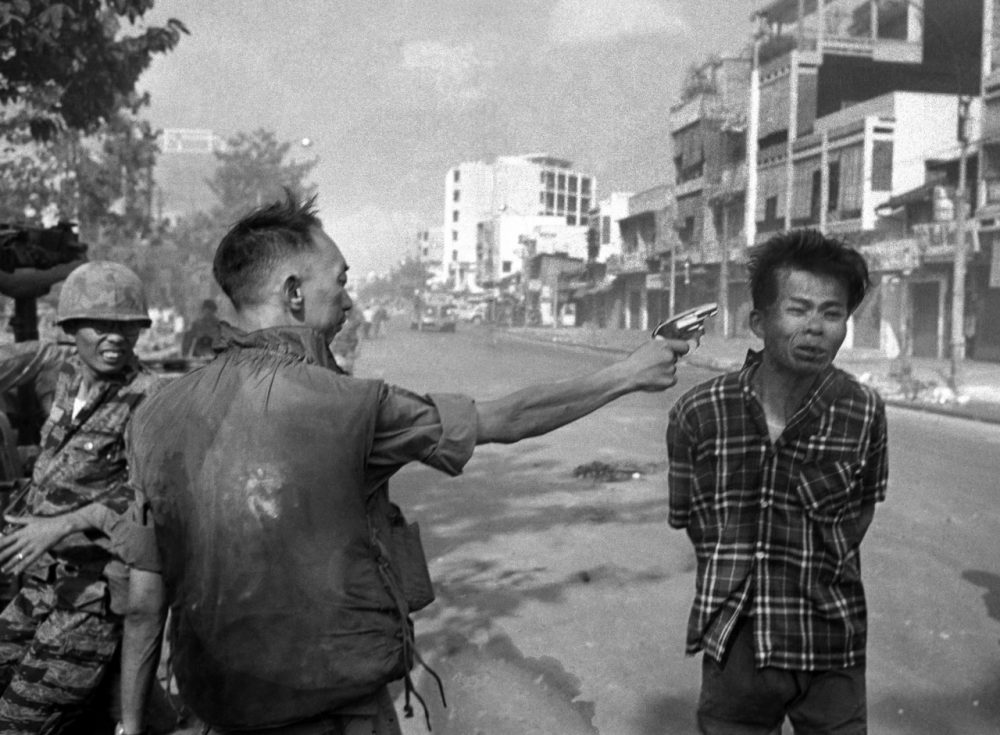

Once again, the raw power of images were hitting people's emotions. It would surprise no one living in today's political climate that the nation was severely divided over the war and the cultural shift taking place in reaction to it. A photo like "The Terror of War" was a visceral shock. The public was already reeling from losing their family members and friends to the war, and now it appeared that our country was killing women and children. There were rumors of officers ordering attacks on undefended villages filled with civilians. Network news crews were now filming some of these incidents.

Popular CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite dutifully reported the news of the day, mostly as told to him by US military sources. Out of patriotism and concern for the public, some of the reporting was sanitized - there was not a lot of carnage shown on network TV. But the photos, film and other evidence were piling up. His own reporters were challenging the party line. When photos like "Napalm Girl" circulated and reporters from his own network began to contradict official press releases from the Pentagon and White House, Cronkite began to question the war himself.

After the Tet Offensive in 1968, "Uncle Walter" as he was affectionately known, traveled to Vietnam to have a close-up look himself. Upon his return, he produced a special on the war and dutifully reported what the generals told him and what he observed there. There was no blood, nothing too sensational... there were no body bags in the report. But at the end, he offered his opinion (and he made it clear that it was his opinion) on the war:

“It seems now more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate . . . It is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could.

“This is Walter Cronkite. Good night.”

This became known as the "Cronkite Moment." President Johnson reportedly remarked, "If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost Middle America.” And not long after that, LBJ announced that he would not seek a second term.

Have I mentioned that photos are powerful?

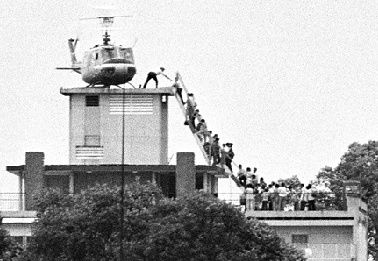

By the way, Vietnam was the last US war that reporters were allowed free access to military operations. In the several Gulf and Middle Eastern conflicts or operations or whatever the government calls them (just not 'war!') members of official press organizations were "embedded" with specific units. Most reports were embargoed for a time, and often reviewed before they were allowed to be published or aired. If journalists went out on their own, the military would not guarantee their protection. Many areas, operations, and personnel were off-limits as far as interviews, reporting, and most importantly, photography. The military would not make the same mistake that they had made in Vietnam.

President George W. Bush outlawed photos of coffins of American soldiers during the Iraq/Afghanistan "preemptive" wars. (This was actually a continuation of his dad's policy put into place during the first Gulf War.) Remembering the power of photos, W and Co. were afraid that it would too easily remind Americans of the human cost of war. The official reason was to protect the families of the dead from exploitive images. In the interest of transparency, President Obama had his defense secretary Robert Gates come up with a policy that allowed families to participate in the decision to release photos. (This is similar to a long-standing policy at Arlington National Cemetery.)

I could show you more, many more photos that would instantly conjure up emotional responses regarding their subject matter. Iconic images that would instantly frame stories from your subconscious.

These Photos Have Power?

But wait. How "honest" a story do these photos really tell? How much power do these photos really have? Is the story that they tell the same story for everyone?

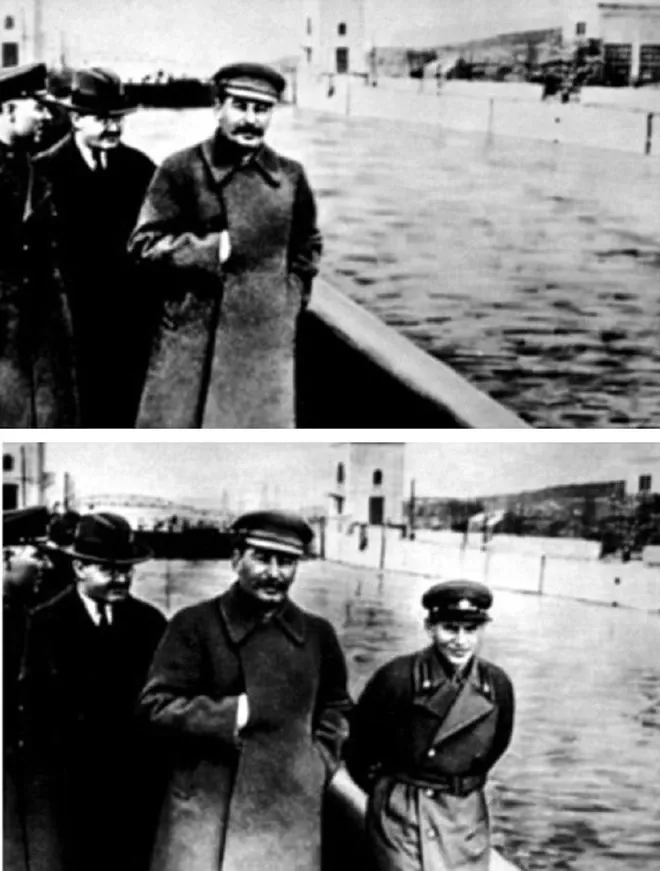

I've shown you that as far back as the Civil War, photos can be manipulated for purposes of telling a particular story. Maybe it's the way that some corpses were arranged, or what was in the background. Sometimes it was just the photographer's aesthetic. Maybe action photos can be restaged for better effect, whatever effect may be desired. So can you trust the photographer that made that "factual" photo? We live in a world now of "fake news" and photoshopped images. Could the photo have been manipulated after-the-fact? Even before Photoshop, there were ways to physically retouch images, sometimes in insignificant ways. Other times, for purposes of pure propaganda.

We're in a period when manipulated images are the rule, not the exception. Most often for purposes of aesthetic, but computers have made it ridiculously easy for photos to be (basically) manufactured out of whole cloth.

Computers are also now producing "deep fakes" so convincing that it will be almost impossible to differentiate real video from phony animation. "Deep fakes" are manipulated videos that are essentially the film equivalent to photoshopped pictures. But voices, faces, backgrounds, crowds... anything that can be filmed can be realistically faked. Remember how audiences thought that the "historic" scenes in "Forest Gump" looked real? These new deep fakes make Forest look like a bad cartoon.

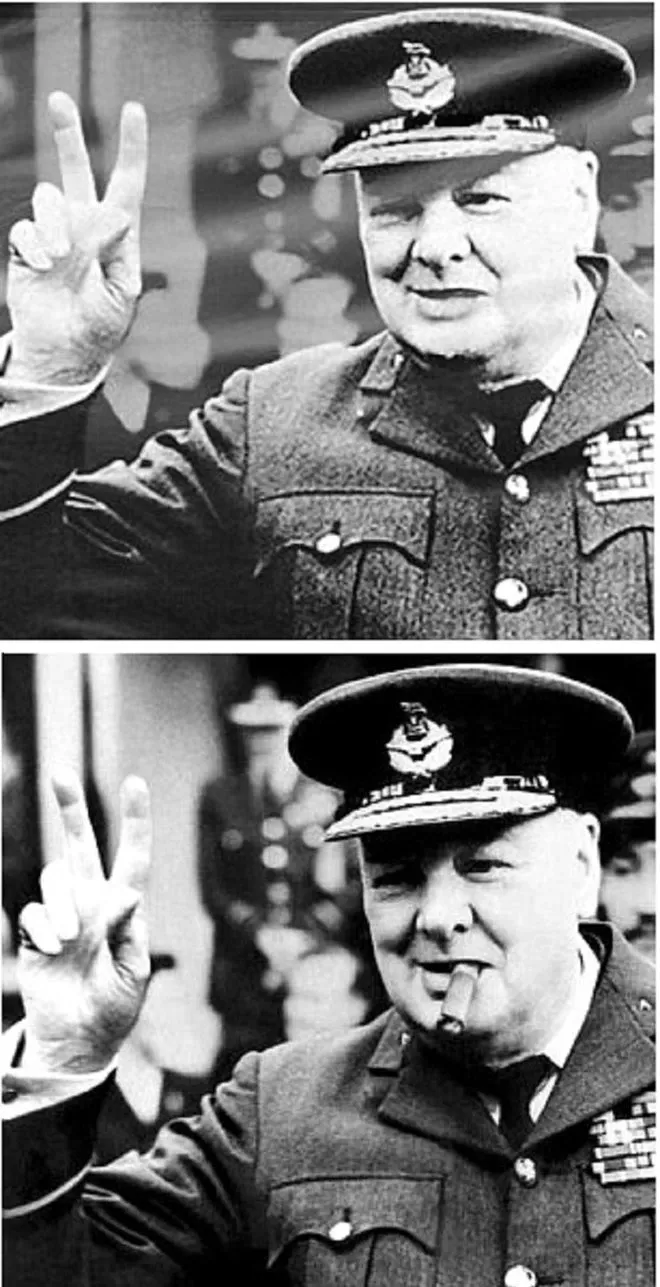

Here's a silly example that will give you an idea of how powerful this tool is:

An expert in video analysis, or someone who took a little time to study the faces there might be able to discern the difference between these fakes and the real actors... but by then? Millions have seen it and are convinced that this is the real thing (potentially... apply this to your own devious plans...)

And what if those experts soundly debunk the authenticity of a particular "deep fake? As Mark Twain said in 1919, “A lie can travel around the world and back again while the truth is lacing up its boots.” *

*Uh.... There is great doubt that Twain ever said this, and he most definitely died in 1910. So... to my point...

And to the fakers, it doesn't matter if you are aware of or later discover the subterfuge. The argument over real/fake and truth/lies is the goal. Planting the seed of doubt is the game. If I can convince you that you just can't trust the media/government/school-system/medical-establishment, then I can probably convince you to believe me (or any conspiracy that I endorse,) no matter what I say. If I can get you to believe that Obama was born in Africa, 9/11 was an inside job, or that millions of illegal immigrants threw an election, then I can get you to believe that I can fix all that. Vote for me! I'm the honest guy!

We don't even believe in a common set of facts anymore. An assistant to President Trump, Kellyanne Conway, insisted that there were "alternative facts." She had been asked why the president's press secretary had denied that Trump's inauguration was more sparsely attended than Obama's despite (unretouched) photo evidence to the contrary.

Alternative facts. Facts recorded by photographers.

And let's face it, those pictures that "tell a story?" They're our stories. We bring our internal biases, preferences, backgrounds, and most importantly - tribal values to everything we hear, read, and see. We react emotionally to those iconic photos, but we bring our own stories to the images as we form our own narratives.

What is the photo above? If you're a German in the 1930s, it's a story of strength, unity, and a resurgent Germany rising from the ashes of WWI. If you're from the West, you see the rise of fascism threatening Europe and the rest of the world.

How about these?

What "story" do they tell? Virulent Racism on the march? Fascism on the rise in the USA? Or ... a protest against the erasure of good old Southern cracker tradition? Remember, even the president of the United States of America observed that "there were good people on both sides." His was not an isolated opinion, but his imprimatur gave a lot of "good people" validation for every racist, violent bone in their bodies.

And all those photos above, the ones so obvious, the ones that changed history?

Mathew Brady was a "Yankee," so there are very few of his photos that "tell" the South's story, as twisted as their Lost Cause was. (Or would we understand their story differently if we had seen the war through the lens of someone as articulate in his craft as Brady was?)

The "Napalm Girl," was not a victim of American bombers. Though reported accurately at the time, (a South Vietnamese pilot had incorrectly identified a group of people as an enemy force and dropped his napalm on civilians,) the public's assumption was that these families had been attacked by Americans.

But did that photo and the opinions it stirred up hasten the end of the war? Was public opinion truly swayed? From a CNN report looking at the 50th anniversary of the photo:

There is no evidence to support the apocryphal claim that "Napalm Girl" accelerated the end of the Vietnam War, which continued until 1975 and saw the communists eventually take control of the country's US-backed south. Nor did it appear to greatly impact American public opinion, which had already turned against US involvement in the conflict by the late 1960s (American military presence in South Vietnam had, after almost two decades, been almost entirely withdrawn by the time Ut captured his image). But the photo became a symbol of anti-war sentiment nonetheless.

Its depiction of the horrors of napalm was so poignant that Richard Nixon privately queried whether it was "a fix." In White House recordings released decades later, the US President speculated that the picture had been staged -- an accusation that Ut said had made him "so upset."

And did you note that Nixon thought it was fake? A conspiracy man's conspiracy.

We can't seem to be sure of a photo's honesty. Maybe their power isn't great enough to facilitate change. And for every story we're sure of, someone else defines a different narrative.

The Unseen Photos from Uvalde

What would happen if we saw photos of that crime scene from the Uvalde school shooting? The pile of children huddled in the corner and then shot, literally to pieces. At least two children were decapitated. There was so little left of several of them that they had to be identified by DNA and a few shreds of recognizable clothing. If we saw a picture of that scene, would our stomachs turn enough to lighten our hearts and motivate our heads to act against this madness?

Would the bottomless grief of a mother or father holding up one of those pictures to the world finally shame us? Could we at last feel enough sympathy to give up our personally owned weapons of war or at least limit who might have them?

My fear is: no. Schools have been shot up before, including the slaughtered children of Sandy Hooks. Radio blowhards/supplement sellers have proclaimed those reported facts as "fake," or "staged by crisis actors working for a government who wants to take away your guns! Now send in $30 for two month supply of testosterone tablets." Bible study groups have been assassinated. Concert goers, movie audiences, church congregations...gunned down. We've never reflected on it before, we've just bought more guns.

This week, Texas Senator John Cornyn (A+ rated by the NRA) addressed the Texas Republican Convention after working with a bipartisan group in the Senate for the past few days to put a bill together to strengthen a couple of background check laws. He assured his base that he would never, ever approve universal background checks or ANY ban on assault rifles. According to Courthouse News Service:

The proposal would implement an investigative period to review buyers’ juvenile court, police and mental health records if they are under 21 years of age before they may buy firearms, a measure Cornyn believes would have prevented the Uvalde shootings.

The bill includes a federal grant program to incentivize states to pass red-flag laws, which permit guns to be temporarily removed, via court orders, from people who have threatened to hurt others or themselves.

But the deal has floundered this week over efforts to come to an agreement on the wording of a section intended to bar people who have abused a romantic partner from buying guns, just as existing federal law allows these bans for those convicted of abusing a spouse, a live-in partner or a partner with whom they have a child.

Cornyn was boo'ed and jeered so loudly at the Convention, that it was hard to hear any of his amplified speech. A Texas GOP committee lost no time in passing a resolution decrying any gun purchase waiting period, any red flag laws, and declaring that “all gun control is a violation of the Second Amendment and our God-given rights.”

Gee, John. Why are you messing with God and those rights that he passed out?

I predict that if any photos of those massacred children in Uvalde find their way to publication, those conventioneers will just boo more loudly. A public picture of that grizzly scene would only reveal who our neighbors really are. And that's already upsetting to realize. Our country has made the decision: My gun is more important than your child, and possibly even my child.

Mamie Till's exhortation, "Let the people see what they did to my boy," didn't shut down the Jim Crow south.

Perhaps it was a ripple, though. We can't say that a single image, a photo snapped at 1/100th of a second changed the world. But Ms. Till's courage energized the movement. Yes, there were more lynchings, more violence, more injustice... her own son's killers walked free (and later openly admitted to the murders.) The aggrieved "white woman" who was supposedly offended recanted her story.

The Civil Rights Act wasn't passed until 1964, by the same president who escalated a foolhardy war in Viet Nam. But Ms. Till and Rosa Parks are recognized to this day as catalysts in the movement, which of course, still continues. Just ask the families of Eric Garner and George Floyd.

If a parent has the courage to do it, I hope that they'll hold up those photos. I hope that we, as a people, have something left in the way of humanity, some tiny spark of compassion left in us that might redeem us, might save our society.

I'm afraid of what that camera saw. But I'm much more afraid that it won't matter anymore. A picture is not much protection from the business end of an AR15.