Cutting for Sign

"Ten children were taken by that storm and their bodies were found but the Guadalupe has yet to surrender even the slightest trace of John Bankston, Jr."

"We need the tonic of wildness. At the same time that we are earnest to explore and learn all things, we require that all things be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be indefinitely wild, unsurveyed and unfathomed by us because unfathomable. We can never have enough of nature." - Thoreau

I rode up to the headwaters of two rivers in one day. Motorcycles can simplify such accomplishments. The Guadalupe I knew well and had traveled much of its length in a canoe and raft, and I had seen it in a fierce flood that had taken innocent lives. Upstream where the river moves placidly over shining limestone beds it is not easy to imagine killing rushes of water leaving float piles of debris a hundred feet up in the branches of an ancient cypress, but it is not uncommon.

Thirty-five years ago, near Comfort, Texas the rain was falling with immeasurable power and there were children trapped on the wrong side of the Guadalupe. They had come to stay at a church camp in the hill country and their visit was ending. A bus driver had decided to get them out before the storm left them stranded and he drove to a low water crossing. The awkward yellow beast stalled out as the water rose against the under carriage and the children began to scream and panic as it entered the door and windows.

Soil does not absorb or stop water in a Central Texas rainstorm. There is nothing but rock and the water finds its lowest level, which is always a river or stream. Unrelenting rain can build into a tall, cumulative wave that moves downhill like a confined tsunami and destroys what man or nature has put in its path. Only the mighty cypress seems strong enough to withstand the river’s strength.

The children on the bus that morning were in mortal danger and several of them lived because of a young man of great heart and small fear. John Bankston, Jr., was a football player and weightlifter and he carried others on his back to safety.

“He just was going back and back, and the water kept coming up, and he started swimming with those little ones on his back,” a witness told our TV camera. “He didn’t stop, neither, even when the water filled up the bus, and then that wave come down and they were all gone, just like that.”

The number of lives lost that morning is known with painful accuracy but how many were given a future by John Bankston, Jr. is still difficult to determine. Bodies were found under brush piles and the root-tangled riverbank and tossed far into ranch lands as the water pulled back. An initial survivor, a teenaged girl, was discovered alive almost 100 feet up in a cypress. A news helicopter flew close and offered her a rope, which she grasped, fiercely, but not long enough for her to be lowered safely to the ground. Her grip loosened and she fell to her death while TV cameras recorded the horror.

Had the bus crossed the river a few seconds earlier there might have never been such a tragedy.

“All the rivers run unto the sea, but the sea is not full.”

All of the lost and the living were recovered, except for John Bankston, Jr. The Guadalupe swept him away and has taken him downriver to an awful anonymity. Long after search crews had given up, I flew in a helicopter with his father up and down the twisting reaches of the river and listened to his refusal to stop hoping.

“My boy was a strong, strong kid,” he said. “Johnny could’ve survived this if anyone could. We know what he did to help everyone else. That’s just like him. He’s out here somewhere. Might even be alive.”

But he was not. Ten children were taken by that storm and their bodies were found but the Guadalupe has yet to surrender even the slightest trace of John Bankston, Jr.

Riding over the low water crossings of the river on my way west I was still unable to imagine such a flood. The Guadalupe is a languorous spring-fed flow that offers mostly shallow pools and views to clear, stony bottoms. The crystalline reflection of a late spring sun was almost blinding but offered no evidence nature might wrest such a tragic moment from an idyllic setting.

Any road west will do.

The big BMW motorbike was nearly as silent as a trickling river and took me up a slow rise to a box canyon that had long ago birthed another river. A visitor follows the water back up to a limestone cliff where hundreds of springs leak from the rock and gather into a flow that becomes the Frio River. Once known to beer marketers as the “Land of 1100 Springs,” a 10,000-acre ranch was worked along these headwaters by descendants of Stephen F. Austin’s sister.

Frio Canyon

Oma Bell Perry, who had never married, and her sister, deeded the land over to Gary Priour, the poet-philanthropist who has devoted his adult life to raising children broken by unfair circumstances of their birth. Invisible hands, Priour has always claimed, guide his work, and when visitors see children playing in the water beneath the Texas sun, they understand why the ranch’s location is now referred to as “The Canyon of Angels.”

The highway through Frio Canyon unspools from the hill country twists to an easy run toward Uvalde. The hills are almost Irish green and treed with live oak and cottonwood and the tall cypress that always find the water. I slow the bike and stop for pictures without thinking I might be keeping a friend waiting down on Highway 90. Leakey and Utopia, dreamy little country towns, demand lingering but I pass through as quickly as though I were watching a movie and roll the throttle up.

Jake and I connect and move in the direction of the sun, riding parallel to the Rio Grande. His bike shines and rumbles in the southwest sun as we get west of Del Rio. The sky must be as clear and blue as the day the world began to spin. Bluebonnets and paint brush spread out over the rocky hills and color the desert. Water from Lake Amistad is backed up into what ought to be dusty arroyos that have been transformed into canals and waterways that are settings for large vacation homes owned by wealthy Mexicans. The vistas are improbable after the urban franchise sprawl of Del Rio, an unusual border town that is surrendering to American homogenization.

The sky gets bigger and consumes the countryside. We catch glimpses of Amistad between the low mesas until U.S. 90 points down toward a river bridge. The Pecos, rarely much wider than a city sidewalk, has cut a deep canyon on approach to the lake. Water appears to be hardly moving but from above it is clear and shimmering in the breeze. The watercourse of the Pecos, which is mostly through the arid ranch country along the eastern perimeter of the Chihuahua Desert, has made it one of the most disputed water sources in the civilized world.

The Pecos at its mightiest near the border

There are still lawsuits over its diversion and consumption and when you stand on its bank and taste the sweetness of the water in 100-degree heat, surrounded by rock, sand, and cactus, you understand why it has been treated as sacred by every human who has lived within its watershed. Encircled by ocotillo and pinon and cholla in the rising spring heat and staring down at the Pecos from the bridge, I end up thinking about the delta down on the Gulf Coast where the Old and the Lost River sweeps to the sea. Those two waterways always have looked to me as though they have the capacity to slake the thirst of all seven billion souls on board our little ship even as we shoot at each other across a stream like the Pecos.

The world continues to confound me.

When the road levels out farther west, we see the green and white Border Patrol vehicles dragging tires behind them on a long rope. A dirt track has been bladed beside the highway beyond the bar ditch and up next to the fence line. The dusty line runs west to Sanderson and then beyond toward Marathon and there are several of the government SUVs pulling tires and covering their tracks.

Unless you know the border, there is no context for such an absurd endeavor. River crossers with the right gear and water and food often come to these remote spots to enter the U.S. They are sometimes carrying backpacks with marijuana or other “contradbando,” or they are just determined spirits that believe they can survive anything if they just get to America. The soil itself holds a magic for them. They are often wrong, though. The Border Patrol drags the dirt to make footprints visible and to know where to go to capture the transgressor.

“Seems to me we ought to want those guys here,” Russ said over breakfast in Marathon. “Anybody gets that far; they are pretty damned determined and might be useful in a country like ours.”

There were three of us at the table, each with a full head of hair, and not a single strand showed any color. We only looked like we might have a touch of wisdom. Such a judgment was only marginally accurate.

“Just seems to me like an insane waste of money,” I said. “Doesn’t appear to offer much of a return on investment by catching a few pounds of marijuana or the lone border runner.”

“Well, Jimmy, we don’t have much say about it either way,” Jake said. “It’s just the way it is along that river.”

“They’ve been doing that drag and detect foolishness since I was a kid,” Russ said. “No way of knowing if it’s effective.”

“It’s effective at spending government tax money and keeping people employed,” I said. “And I suspect that’s what matters more than few pounds of pot being confiscated. Makes politicians feel better, too. Secure the border!!”

Jake and I sped south toward the national park after breakfast and watched the clouds shred themselves on the Glass Mountains. The sky above was clear and blue but the pretty people on the motel TV had said rain was likely before sundown. I was skeptical as we began the sharp climb up to the Chisos Basin a few hours later because we stopped and looked behind us to the north and the air was pure enough to almost make visible McDonald Observatory about 150 miles distant.

The park road curled so sharply it almost felt as if it were twisting back onto itself and we slowly rose to altitude past the signs warning about bears and panthers. The ancient world was visible from up there and looking through “The Window” that opened up between two mountains at the desert floor, I had no trouble imagining great prehistoric species stalking the far plains.

The Window

We ended up on the porch of the general store in Terlingua, a ghost town that thrived briefly during a global demand for mercury. There is now the little store and the Starlight Restaurant and rustic adobes turned into pricey bed and breakfast establishments. A few cantinas and burger joints are along the bumpy road up the hill. The predominant feature, though, is the graveyard with Spanish surnames cut crudely into stone or desiccated wood crosses, many of them tilted by weather and time.

I went to the icebox in the general store and got two Tecates and came back out to sit on the bench that spans the front of the building and looks out over the long slope back to the river. The Chisos cut a ragged line across the horizon as we looked eastward toward the park and leaned against the wall to talk with the assembled strangers.

“Where’d you two ride from?”

The question was from a young man in a dirty baseball cap, jeans, and work boots. His dark tee shirt was sweated through and dirty but it was not torn.

“Different places. Austin and the Rio Grande Valley,” I said.

“I need to get to Austin some day,” he said. “But it’s just another big, corporate city now, I suppose.”

“There’s more than just a touch of that, for sure,” I said. “Whatever we used to like about it thirty years ago is slipping away. Where are you from?”

“Oh, Connecticut.”

“Really? What in the hell got you out here?”

“I just wanted to get as far away from corporate bullshit as I could and this looked like the best spot on the map.”

“You don’t look old enough to be fed up with climbing the corporate ladder.”

He cut his eyes at me but then smiled. “Well, I am. I hated it. I had a good job. But it was all politics and caring about shit that seemed pretty stupid to me. Out here, I work when I want, do what I want, and nobody cares what I think or do.”

“I guess that’s worth more than a corporate salary.”

“It is,” he said, and then pointed to the Chisos. “The light at the end of the day on those ranges never gets old to me. Ain’t it funny? This is probably the only place in America where people come to sit and see the sunset by looking east at those mountains.”

The people who live in the desert around the ghost town all have a story about wanting to be away from the world. They move up into the remote stretches and build adobes and survive off the grid but never have to impress another human or answer any questions. I have met government agents and truck drivers and drug runners sitting the sun on that general store porch and they all view privacy as Terlingua’s most precious commodity.

We got back on the bikes and went north toward Alpine. Crossing deserts on a motorcycle always leaves me with a sense that even the most mundane human act takes on epic proportions. Closing a door or simply walking across a street feels like it has a connectedness to some grander endeavor, which cannot immediately be known. This is mostly delusional, I suppose, but no one ever seems to simply watch the rain as it falls after a storm arrives in a desert; they appear to be battling the elements before an incomprehensible backdrop. I have ridden across the Mojave, Sonoran, and Chihuahua deserts many times and up and down the Great Basin and have always expected the universe to reveal secrets as the road endlessly extends.

More than an hour out of Alpine we had ridden under a black sky and left the sun shining behind us on the canyons of the Rio Grande. Lightning shot across our view in sharp-edged bolts and the thunderclaps were disturbing even above the wind and engine noise. When we rode into the rain, we were drenched in minutes, and as we came over each rise I looked to the north for a break in the sky and a furtive hope our destination might yet be dry.

Curtains of rain hung over the high mesas to our east and the inky black in some parts of the cloud cover faded to gray. Rain sways as belts in the far wind. Immediately, small breaks appeared in the storm and the sun found a few white basalt hills and dried out ranges and illuminated them in the afternoon darkness. A spotlight was cast across our front and onto a scene as old and eroded as it can be made by time and the elements. The show was almost more than could be imagined because the light and the dark and the rain and the desert offered such contrasts in microcosm.

“I prayed all the way through that storm, Jimmy,” Jake said later. “I got us some good mojo.”

We are eating thick steaks at the Reata and trying to dry out over dinner. Friday night was working hard to be exciting outside in Alpine.

“I guess you got us some magic then, Jake. Here we are. Wet but alive. And you’ll remember that stretch of Texas highway, I bet.”

“Yeah, but let’s not do that again real soon, pardner.”

“Let’s see what the ride looks like back to Marathon.”

The storm was rolling east as we ate, and we lingered to give it time enough to pass but as we went back down U.S. 90 the lightning lit our way. We did not hear thunder, but the cell was curling back on its own cloud tops and peeling away toward Del Rio, leaving great flashes of light across the night as it receded. We slowed enough to let the weather guide us down the road, but we were still surrounded by momentary brightness and daggers of light that seemed like cannon shot and were frequent enough that they might eventually find their targets.

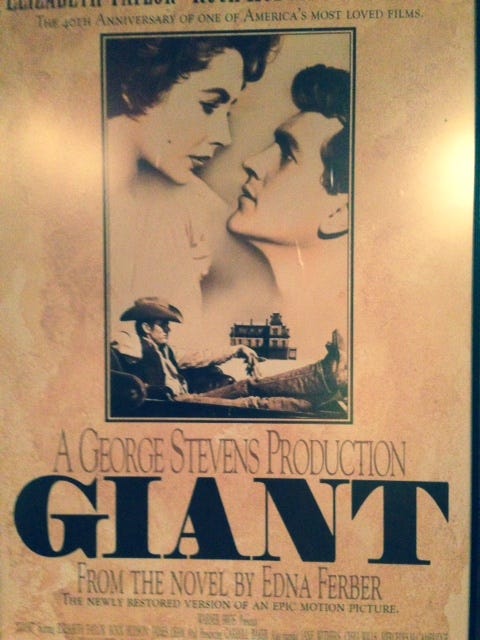

We had dined also in Marfa at the old Paisano Hotel, and I was confident the ghosts of Liz Taylor, Rock Hudson, James Dean, and Dennis Hopper were shuffling the halls looking for their rooms and wondering what had happened to the desert ranch town they had left behind after filming Edna Ferber’s “Giant.” I worried greatly about the monsoon and lightning also turning us into something incorporeal.

Almost biblical rain had fallen in Marathon by the time we parked our bikes. Six to eight inches running across the rock and finding the dry arroyos, eventually reaching the Rio Grande.

Jake took off his helmet and smiled in the dim light from the cabins. “Got ya more mojo there, too, brother. Kept ya safe all the way in.”

“Yep, you are, from here on, Lightnin’ Jake.”

The magical desert sky and the western landscapes had fooled me yet again.

I was certain I was immortal.