Growing Up

"We were a Dixie Diaspora, believing hard work was the magic for fulfilling dreams, not just breaking backs and hearts. The repeated tasks of a factory floor held more allure than swinging a hoe and chopping cotton along the Mississippi River, but it might have even been harder on the spirit."

“Wasn’t it beautiful when you believed in everything?” - Taylor Swift

Winters were brutal. We sometimes had only nylon jackets to protect us against the Michigan cold, and old socks served as gloves. I tried to time my walk to the school bus stop to arrive just as the driver opened the door to the steps inside but I was always early and spent time shivering in the morning dark. My fingertips often went numb while we waited. Our parents worked hard and long hours but there were six kids and usually not enough money for warm winter coats. When the bus delivered me to our urban high school, I frequently felt I was being deposited on another planet. My classmates wore puffy down jackets and ski lift tickets were stapled to their zippers to show their peers they had spent the weekend on the northern hills.

I tried constantly to think of a time someday when I might not live different and underprivileged. My initial dreams of a more comfortable future came from listening to an old clock radio. When it clicked to wake me up for school, network reports from around the world were already being broadcast. I thought no one had a better job than the global correspondents of CBS Radio News. They were dispatched to write and report on important issues in lands foreign and exotic, and I wanted the same career. Sometimes, on my long training runs in the summers, I would practice my radio outcues and tried to sound as convincing as, “Charles Collingwood, CBS News, the Khyber Pass.” People driving past me on the road may have thought I was talking to myself but I did not care. In the library after school, I made it a point to find the World Book Encyclopedia to learn the location of the Khyber Pass, which meant, I was ready, therefore, to leave on my first assignment.

My first jobs, though, were a great distance from a network news paycheck. I landed work at a veterinarian’s office making a minimum wage to clean out animal cages on weekend mornings. The tasks were nauseating because the floors of each cage were covered with newspapers that had been freshly fouled by dog or cat excrement and urine. The animal urine had also dried overnight and essentially glued the paper to the bottom of the cage. A forced pressure garden hose, supplied by the vet, did not wash the papers loose and I tended to have to scrub them clean on my hands and knees after I had removed the feces. When all of the cages were dried and readied with fresh paper, and I had brought the household pets back inside from the outdoor pens, I picked up the hose and washed the collected messes into a “honey pot” in the center of the room. I made about $40 dollars for a weekend’s labor. Also, there was no honey in that pot.

Strangely, my second employer had a business that also dealt with feces, though I think I was hired without regard to my experience with the animals. As our township grew, homes that were on septic systems were required to disconnect and hook up to municipal sewer lines. The owner of the company that had hired me had built a business by installing the connections and very quickly moving on to the next house. There were no regulations about shoring up excavations or legally allowable depths for certain projects, which meant he found the outlet pipe at the foundation of the house and used his backhoe to dig a deep gash in the earth that led to the curbside hookup. I spent my day down in that trench while he handed me the crock pipes from up top. I slid them together and constantly watched the dirt walls for signs of collapse, which happened a half dozen times when he dug below ten feet. I ran toward the shallow end and often barely escaped.

I did not have the naïveté needed to maintain youthful optimism about a prosperous life. My immediate fear, even before thinking about a college education, was that I had slipped into an existence that was about labor and low pay and I might become forever trapped. The neighborhood where we lived was made up of modest tract homes, 800-900 square feet, and the ten-thousand-dollar mortgages on VA loans were still difficult for the families up from the south that worked the factories. We were a Dixie Diaspora, spread across an oval that used to be a cow pasture, believing hard work was the magic for fulfilling dreams, not just breaking backs and hearts. The repeated tasks of a factory floor held more allure than swinging a hoe and chopping cotton in the dark bottomlands of the Mississippi River, but it turned out they might have even been harder on the spirit.

The automotive production facility in the center of our lives was referred to as “the tank plant.” Sherman Tanks by the thousands had rolled off its assembly lines during World War II before it was reconverted to automobile assembly during peacetime. Families of executives and managers and foremen lived in planned communities on the east side and the assembly line workers and laborers were only able to afford homes available adjacent to the less desirable western gate of the plant. While families were separated by income and opportunity, the real dividing line, however, was race, just as it had been in the South. I do not believe there was one African American living in our township during the 1960s, and the entire school system was white. Hillbillies from south of the Mason-Dixon and home from the war, desperate for work, had still managed to segregate themselves from black families. Flint, which was elemental to the automotive boom, by 1970 had a population of just under 190,000, and more than a fourth of the demographics were represented by the 54,000 African Americans. None of them lived among us.

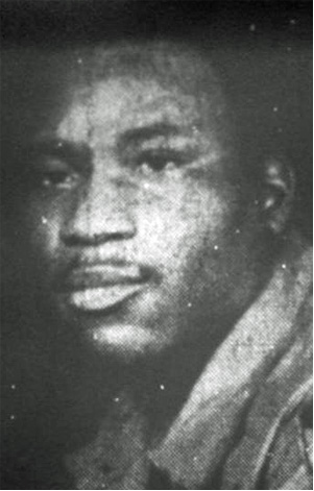

Because the high school where I was to graduate remained all white into the early seventies, I did not encounter black people except through sports. Ectomorphic and quick, I was drawn to distance running and began to make friends outside of school as I traveled to track and field meets. The only athlete I remember from those days was a sprinter from Flint Southwestern High School, who was the first African American to ever befriend me. His name was Roy Raymond Dukes, and he was almost spectral with speed as he moved around a quarter-mile track. The first time I saw him run was at the George Graves Relays up in Midland, Michigan, and I was stunned at how effortlessly he moved away from the competition. His heels never brushed the track and when Dukes drove his knee high in his sprinting motion, his foot actually made a slight popping sound against his butt. His legs appeared to scissor up the yards in seconds and there was no audible sound of him breathing with any effort. Barrel-chested and narrow-waisted, Dukes had no peer in mid-Michigan track and field into the late sixties, and few compared anywhere in the country. Five decades after completing high school, I still take out an old scrapbook to look at him winning a relay, his perfect form leaning into the tape and smiling a victor’s joy in a black and white photo recorded by his hometown newspaper.

An African American from Flint’s South Side, I assumed Roy’s physical prowess on the track was certain to ensure his future. He ought to have been offered numerous full-ride scholarships to major universities. We only spoke when our schools were in the same multi-team events, and when I asked where he planned to go to college, Roy only said he was not sure. I did not press the question and assumed there were several fine options that would allow him to explore his natural gifts as a sprinter. Any coach or runner who saw Roy lean fiercely into a turn or explode down a straightaway knew they were witnessing something extraordinary, a talent almost unique. When the field announcer called for the sprinters to report to a starting judge, many of the other athletes, who were stretching or jogging to get loose for their races, simply stopped and stood trackside to watch Roy Dukes blow past on his path to inevitable victory.

Because he was a year ahead of me, I lost track of Roy Dukes and his running career. I expected to read in the newspaper that he had qualified for the 1972 U.S. Olympic Team in the 400 meters and the 1600 relay. Instead, when I saw his name in a small dispatch in a back section of the paper, it was a few paragraphs to report that Roy Raymond Dukes had died in Vietnam at age twenty. Private First-Class Dukes was lost to what the U.S. Army’s report said was a “non-hostile injury, accidental self-destruction, ground casualty.” The descriptive meant he most likely lost died in an accident that was self-inflicted. Dukes might have mishandled his gun or accidentally pulled the pin on a grenade.

He had been in Vietnam for exactly two months and one day. No further detail was offered by the government that had drafted him into its meaningless war. The fatal incident occurred at Phuoc Long Province, South Vietnam, while he was serving as an infantryman in light arms with the D Troop, First Squadron of the 9th Cavalry of the 1st Cavalry Division. One of the few indications Roy Raymond Dukes lived is now on panel 4 W, line 18, of the Vietnam Memorial. I have made it my habit to visit on every trip to Washington, D.C., and I have never stopped being angry. Whenever I saw him run, I was certain I was witnessing a future Olympic Gold Medalist.

The death of Roy Dukes was an indirect consequence of the assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy. JFK had made it clear that he was tired of the morass developing in Vietnam and had indicated he was going to start the drawdown of troops at the end of 1963. The president had signed National Security Action Memorandum 263 with those orders included but also instructed that the reduction in force was not to be made public until the beginning of the new year. Unfortunately, the domestic political, economic, and military forces that conspired to kill Kennedy wanted a war and were angry about his attempts at détente with Russia and Cuba. When JFK was succeeded by LBJ, America escalated the conflict with a false flag incident at the Gulf of Tonkin, and hundreds of thousands of young men were shipped into combat using a specious political theory that Communism had to be stopped in Southeast Asia before it reached our shores. Our country has never owned the truth that those lives were wasted.

I got word of the president’s murder in middle school when I climbed up the steps to my bus to go home that autumn day of 1963. Our bus driver was leaning over and resting her head on her arms against the steering wheel and sobbing. When she explained what was causing her sadness, I sat and stared out the window at swirling Michigan snow and wondered what was going to happen next to our country. How did things work when something like this happened? Kennedy had got us through a nuclear standoff with Russia over missiles in Cuba, but as young students, we were still practicing the duck and cover drills in class to protect ourselves from an atomic bomb. We were supposed to believe cinder block walls, single pane glass, and Formica desktops would prevent us from being vaporized by a thermonuclear explosion.

The only understanding I acquired came from my best friend Gary. Pink-cheeked, pale-skinned, and blonde, a short and mysterious teenager, he had none of the interests of our age group. Bad science fiction movies and obscure books kept him in his room during most days, even when the rare Michigan sun appeared, but he also became politically aware long before his contemporaries, and he used his intellect to provide me with information that was simply not available on the TV or in the local paper. I did not always know where he acquired his knowledge, and I was usually skeptical, but as the years passed, I came to understand how prescient he was for a teenager.

A few years after JFK was slain, Gary banged on the dented front door of our house and hollered for me. He was almost breathless and holding up a book, which I learned was Mark Lane’s Rush to Judgment, the first critical analysis of the coverup of the conspiracy to kill the president and all the evidence left untouched and witnesses never contacted by the Warren Commission. We were barely into our teens and he was already seeing conspiracies in American life.

“You’ve gotta read this,” he said. “This is real. It’s what happened. Not Oswald.”

“What do you mean?”

“They had Kennedy killed. Oswald didn’t do it.”

“I don’t understand. Who’s ‘they?’”

We sat under the only tree in our yard and I started leafing through the book as he tried to explain to me what the missing evidence revealed.

“Somebody wanted him dead. Maybe it’s just people who run the world. The real people; not the government.”

“Man, you are losing me.”

“Just think about the things he did. He’s been trying to make peace with Russia after the Cuban thing, and he even wants to start talking with Castro. That’s in the newspapers. But the military wants war and so do the people who build bombs and guns and ammo. That’s where the big money is.”

“Gare, how do you come up with this stuff?”

“Here, take a look at these.”

A half dozen color pamphlets fell out of his hand onto the grass. When I glanced through them, they were about Brown and Root, Sikorsky Helicopter, and Dow Chemical, the Michigan company that made napalm and Agent Orange to kill the jungle canopy in Southeast Asia, and everything that lived under it, including humans. They were accused in the texts of profiteering off the war and paying lobbyists to promote the Vietnam conflict in Washington to create political support.

“Read that part about the Gulf of Tonkin. That guy said it didn’t even happen. We made it up so we could get involved in the war.”

“What’s the Gulf of Tonkin?”

“Oh, crap. Give me that stuff back.” Gary was frequently exasperated by my lack of awareness. “Don’t you get it? The same guys that make up phony reasons to go to war are the same guys who could get rid of a president if he’s in their way.”

“I don’t know, Gare. That’s kind of hard to believe. I don’t think we’re really like that.”

“Yeah, well you’re wrong, and if this Vietnam thing keeps getting worse, you and I and a bunch of our friends are gonna end up over there and we’ll die.”

Gary had just given me a new fear. Until that moment beneath the sagging maple tree in our front yard, I had spent my time daydreaming about girls, becoming a better baseball player, and even a writer. Why would I have to think about war? There are very few American generations that have not had to suffer the same affliction, though.

As we transitioned into our high school years, Gary kept me informed on the draft and the Civil Rights Movement, and I was diligently reading newspapers and watching the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite. Coverage increased daily about violence in the South and segregationists attempting to stop changes in the law. Vietnam and the struggle for civil rights converged in a powerful fashion in the person of World Heavyweight Boxing Champion Muhammad Ali. The former Cassius Clay, an Olympic Gold Medalist, had changed his name when he joined the Nation of Islam. Ali was the first professional athlete in the television era to use his public reputation to promote social justice, and he became an icon for the Anti-War and Civil Rights Movements.

The fighter also became my personal hero, and Gary’s, who did not have an athletic cell in his entire body. We were in awe of Ali’s utter fearlessness when he refused to step forward after his name was called at an Induction Center for the draft in Houston. He was arrested, prosecuted, and convicted for violation of Selective Service laws, but he never relented in his opposition to an unjust war. Although his conviction was later overturned on a technicality, Ali had been banned from boxing for three years in the prime of his career, but he never quit being blunt about American hypocrisy regarding race and the war.

“Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong,” he said. “Ain’t a one of them called me a nigger. Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights”

Ali, returning from the Olympics wearing a gold medal around his neck, had gone to a Louisville lunch counter in his hometown to eat at a location he had previously been denied service. His accomplishments and international glory changed nothing, and he was told to leave and that the restaurant only served whites. He later threw his gold medal into the Ohio River. White people across the country, accustomed to blacks acquiescing to racist policies, were stunned by the champ’s behavior, and up in Michigan, the son of a man who had been raised to be an unrepentant racist, had found a hero.

Lyndon Johnson’s administration made the first significant legislative attempts to create laws that prevented the types of discrimination endured by Ali and millions of African Americans on a daily basis. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the subsequent Voting Rights Act of 1965 only codified an end to illegal behavior toward blacks but change of the cultural and institutional practices of discrimination took many more years. Martin Luther King, who had been central to creating the political wave that LBJ was astute enough to see on the horizon, did not stop speaking after the civil rights acts were signed into law, however. MLK understood acutely, even more than the politicians who backed the legislation, that it takes more than words on paper to change the human heart.

The President, undoubtedly, felt betrayed by MLK when the reverend spoke out against the Vietnam War. LBJ felt he had risked his political capital in the South to achieve civil rights legislation and a few years later MLK publicly challenged the president’s policies on Vietnam with a speech at the Riverside Church in New York City. The civil rights leader had already begun questioning LBJ’s and America’s approach to Southeast Asia during interviews and lectures, but his oration entitled, “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break the Silence,” King compared the U.S. to Nazi Germany in how the war was being prosecuted.

"What do the peasants think as we ally ourselves with the landlords and as we refuse to put any action into our many words concerning land reform? What do they think as we test out our latest weapons on them, just as the Germans tested out new medicine and new tortures in the concentration camps of Europe? Where are the roots of the independent Vietnam we claim to be building? Is it among these voiceless ones?"

LBJ, privately, was incensed, and my pal Gary was worried.

“You know they aren’t going to let him talk like that, don’t you?”

“We’re talking about ‘they’ again, Gare?”

“Yeah, did you read about MLK’s speech in New York?”

“No, he does a lot of speeches. I know what they are usually about.”

“Yeah, but now he’s attacking the War in Vietnam. LBJ isn’t gonna put up with that crap. Neither is the military.”

“It’s still a free country.”

“No, it’s not. Where have you been?”

“Right here. Listening to you. Just like I always am.”

“Don’t you think if they got rid of JFK, a damn president, for opposing the war, they could sure take care of a black preacher?”

“Oh, come on, man. You don’t really believe that could happen.”

“Of course, I do. And if you don’t, you need to pay closer attention.”

“Sure, Gare. Sure.”

The advances Dr. King was demanding were hardly being met. The black vote was still being suppressed; young African American men were being drafted and sent off to Vietnam in vastly disproportionate numbers to white boys, and unemployment in the black community continued to be higher than it was for the rest of the country. LBJ’s Great Society was mostly an unachieved ideal if you were black, and political rhetoric turned into unenforced regulations was no longer effective in restraining a restive population.

When riots broke out in Detroit, Gary borrowed his brother’s car and did not tell him we were going to drive it into the city to get closer to what we were seeing on the news. I do not know how I let him convince me to take part in such a foolish act, but I was curious. The two of us knew nothing about black people since we were growing up in a segregated community. Our town, Grand Blanc, which translates as “Big White,” was named by French traders who came upon a rise in the land and saw a snow-swept vista. In a demographic sense, we could not have been given a more perfect descriptive. Gary and I only got close enough to see the fires of Detroit burning and our curiosity was overcome by our lack of courage. There was no reason for us to put ourselves at risk. We saw flames in a few distant high rises and heard sirens and turned back toward home with my friend explaining to me that we were probably getting first glimpses of the future of our country. Protest had turned to riot.

Gary’s admonitions about cultural and economic tendons tearing, to make life more dangerous in America, were coming true right in our back yard. The governor had deployed the Michigan National Guard to quell the Detroit riots and President LBJ had ordered the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions to the streets but there were still 43 dead, an estimated 1200 injuries, and about 2000 buildings destroyed. The Motor City was not the only location, either, where discontent over racial inequality prompted violence during the summer of 1967. An unofficial count indicated there were 149 American cities that had experienced significant public disturbances caused by racial unrest. Increasingly, it was becoming obvious that the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act were only aspirational pieces of legislation and nothing of import had truly changed for the overwhelming majority of black people trying to live comfortably in the United States of America.

I suppose every teenager in the country, especially boys who faced the prospects of being drafted into the military, was afraid of being robbed of their future by social instability. My fear was probably a bit more acute because I had Gary, a voracious reader and determined thinker, to constantly inform me of dangers he was certain lay before our careers and adulthood. Little frightened us more than the war and getting drafted. Gary and I considered that we would be casualties inside of our first week walking the bush in Vietnam. We ought to have been more afraid of the families in our neighborhood because Gary kept asking me to bang on doors and hand out anti-war literature to conservative Southern transplants and their households. Anger was the usual response, but he kept thinking they all had sons they did not want to lose in an unjust war. Gary thought he could even convince naïve’ patriots their nation was making a huge mistake and the war was nothing more than a cynical adventure to generate huge profits.

We were conducting this two-man campaign to change the world one chill April evening in Michigan when one of the residents we were pleading with asked if we had heard the news that Martin Luther King had been shot. We ran to Gary’s parents’ house and turned on the TV and silently watched in disbelief, until Gary had processed the situation and offered another one of his theories, which I am not sure I can still even consider as remotely true, which probably implies it is a fact.

“Holy shit,” he said. “It’s a statement.”

“Yeah, it’s a statement, all right, and pretty obvious one: We hate a black man getting people riled up about civil rights and protesting the war.”

The TV was showing people outside of a Memphis hospital where Dr. King had been taken in a vain attempt to save his life.

“No, not that statement.”

“Then what are you talking about now, Gare?”

“I just realized it. What’s the date of today?”

“April 4th, right? 1968.”

“Exactly. Sound familiar?”

“Yeah, April comes around every year. That’s familiar.”

“Not what I meant, smartass.”

“What then?”

He did not answer but turned up the volume on the TV as a reporter started to explain the FBI was looking for a particular suspect. Gary scowled at law enforcement officers speaking to the cameras.

“Sounds like they had a pre-arranged patsy for this one, too,” he said.

“Come on, man. You can’t already be seeing a conspiracy.”

“Why not? It’s in front of your nose, just like JFK.”

“What’s the statement, then?”

“Like I said, think about last year, in April, what we were talking about.”

“I don’t remember, Gare. Just tell me what you are talking about now.”

“I’m talking about what happened exactly one year ago today on April 4, 1970.”

“So, tell me. I don’t have your political memory.”

“It was King’s big speech at the church in New York City, man. The long one where he just blasted the war and talked about how we were nothing more than oppressors and the U.S. was even like Nazi Germany.”

“Yeah, I remember your rant about it and then seeing some clips on TV.”

“So, anti-war resistance increased since then, more protests, and so did civil unrest. You don’t think they were going to let him get away with that shit forever, did you? They saw him as an agitator.”

“I still don’t get what you are saying. What’s the statement?”

“Pretty obvious to me. They killed MLK on precisely the same date as he gave the anti-Vietnam speech last year. Not a coincidence, I guarantee.”

Oh, come on, man? Really? You can’t believe all this.”

“It’s not crap. Just put the pieces together. Not much different than what they did to JFK. And I’m telling you again, it’s not over. Gonna get even worse.”

“How in the hell can it get worse?”

Our conversation ran out after another half hour and I walked home in the darkness, passing underneath the streetlights, thinking about being a kid and playing catch past dark in the circle of brightness cast underneath each pole. Nothing had been better at taking my mind off my parents’ fights and Daddy’s violence. Baseball was only a temporary curative, though, and I always had to go home. There was no hope for a simple game to distract me from what I was seeing on television, and Gary’s predictions about things getting even more untenable had been consistently accurate. How could they become any more horrific?

I fell asleep on the floor in front of our flickering TV set and watched the constant news updates about the MLK assassination and the subsequent outbreak of rioting, and even in my fractured dreams, the world appeared like it was being consumed by an unholy fire.