"High-Tech" Sign-stealing in Baseball History

Mark Twain's favorite nine did it. Yours does too.

First some background.

Ever since hand signals came into baseball, in every at bat of every single game, opposing teams have tried to steal them.

It's comparable to military intelligence, code-breaking, false flag attacks (fake signs to draw out what the opposition knows). Bench and third-base coaches are treasured for their expertise in this area, as are certain players. Pesky lead-off men often have a knack for this dark art. Nobody has more of an opportunity to look in on the catcher, as they are often on base and can see between his legs, and nobody can glean as much information from what they see. They are not only looking to identify the pitch, but also its placement, as both of those factors can aid base-stealing or generalized baserunning.

(Plus, those pesky lead-off guys are just like that. They are wired that way or they wouldn't be professional lead-off men.)

Given all that, the signals your team used in the first inning might become obsolete by the second or third, so you change up.

Or at least you'd better, because there are no rules against sign-stealing, and when perpetrated by players or coaches unaided by technology, the art is condoned by the unwritten Baseball Code. Totally kosher. (Because they are positioned in an advantageous vantage point, whether or not the Code extends to the bullpen is a gray area.)

Former commissioner Bud Selig explicitly said so in 1997, when Giants manager Dusty Baker publicly whined that Felipe Alou's Expos were stealing his signs.

"The dispute is nonsense," Selig told the Chicago Tribune. "The object is to win."

Asked if he approved of the practice, he said, "Why not? It has been going on for years." (What he thought about high-tech sign-stealing is unclear from the context of the article, which makes no distinction between the two gradations of the practice.)

So -- every team steals signs, and has since the dawn of baseball. What is not known, and can never be known for sure, is what percentage of teams have violated the Code via extracurricular sign-stealing, and to what extent they did.

What is certain is that what the Astros have been punished for and what the Red Sox will soon is nothing new. Sometimes teams were found out in real time, and in other cases, only after long decades, only after the diktats of clubhouse omerta had faded, did the truth emerge.

(And what's more, it's global: Davey Johnson recalled that it was routine for teams in the Japanese league to bug opposing clubhouses. So much for the samurai honor code's alleged ties to baseball.)

And so here is my stab at a timeline of high-tech cheating in Major League Baseball.

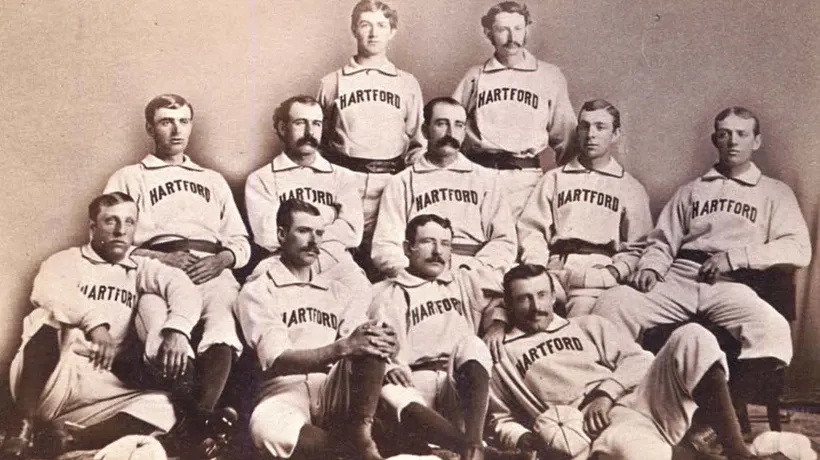

1876: In the inaugural season of National League baseball, the Hartford Dark Blues stood accused of posting a spy with binoculars in a shack suspended on a telegraph pole beyond the outfield wall with orders to signal Dark Blues batsmen when one of those newfangled curveballs was coming. Said a contemporary observer, "A lot of dope came out of that little office."

The Dark Blues finished a respectable 47-21 that year, but that was not enough to save National League baseball in Hartford; the Dark Blues decamped to Brooklyn a year or two later, much to the chagrin of their number one fan: Mark Twain.

Interestingly, in the early days, observers called this practice "tipping the signs," placing the onus of blame on the team careless enough to allow the cracking of their code.

1900: Now we get really high-tech. The Philadelphia Phillies are credited with ushering baseball into the age of electricity.

In the first game of a September doubleheader in Philadelphia's Baker Bowl, Reds shortstop and team captain Tommy Corcoran suddenly emerged from his team's dugout in the third inning of game one, and in the words of a contemporary sports reporter, "walked over to the coach's box at third base in and began to scratch gravel in a way that made Petey Chiles look like a blacksmith." (I guess you had to be there to catch that reference.)

According to that same report, Phillies "groundskeeper Schroeder" and a sergeant of the police force ran on the field in an vain attempt to halt the "Cincinnati generalissimo's" excavations, but too late -- he had already dug up a vault containing "an electric apparatus."

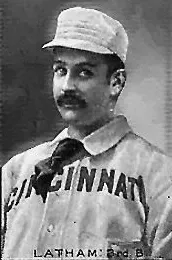

Reds coach Arlie Latham, a rule-stretcher (to put it mildly) himself, was among the first on the scene.

As a third base coach, Latham's shenanigans -- waving his arms, running up and down the baseline willy-nilly, hurling profanities at the opposing pitcher and fielders -- were historic, literally: they ushered in the advent of the coach's box (to rein him in) and won him one of the best nicknames in baseball history: "The Freshest Man on Earth."

So anyway, Latham comes upon this little high-tech crypt and, according to a reporter at a major American daily newspaper, had this to say:

"Ha! Ha! What's this? An infernal machine to disrupt the noble National League, or is it a dastardly attempt on the life of my distinguished friend, Colonel John I. Rogers?"

Apparently "infernal machine" was a reference to the use of mines in the Spanish-American War. I am not sure how Phillies owner Rogers tied into that, but there you go.

Anyway, according to the same reporter, umpire Tim Hurst matched Latham's stentorian oration with one of his own. Nodding to the apparatus, he is alleged to have intoned:

"Back to the mines, men. Think on that eventful day in July when Admiral Dewey went into Manila Bay not giving a tinker's dam for all the mines concealed therein. Come on. Play ball, and blow the Colonel's mine."

(Would that Baseball Twitter resounded with such eloquence.)

Said "colonel's mine" was really a buzzer connected to a wire that ran from the coach's box through the outfield to the Phillie clubhouse beyond the fence. There dwelled a Phillie spy armed with binoculars who would transmit each pitch to the third base coach's foot electronically with this crude telegraph, and the coach would then relay that information to the batter with coded exhortations.

An unnamed third team had tipped off the Reds with their suspicions, it was later revealed. The Phillies, it was later noted, had introduced baseball to the age of Edison.

1909-1910: The Detroit Tigers suspected funny business on a trip to New York. A Detroit trainer scanned the outfield walls and thought he detected suspicious movements in the crossbar of the letter H in a large sign advertising hats. The Detroiter advanced on the sign and found a man inside letter H eating a sandwich. On his discovery, the man fled without a word, and the trainer discovered the lever by which this mole had manipulated the H. The Tigers reported their findings to the league office.

And as would prove to be usual over the next century, the Yankees skated. League president Ban Johnson subjected the Yankees to a "lengthy investigation" and publicly cleared them, fearful that this Yankee perfidy would bring shame and bad press on the game. Privately, he issued them a warning, and yet the reports of Yankee sign stealing continued through the 1910 season. While those reports did lead to the resignation of their manager, nothing came down from the league office.

Decades later, the Yankee's villainous first baseman Hal Chase confirmed that the "Black Hand" scheme was real: the H was maneuvered one of three ways to denote curves, fastballs, and spitballs.

Generalized 1910s, 1920s, 1930s, 1940s and 1950s: Rogers Hornsby was a Hall of Fame second baseman whose playing career spanned four teams and 23 seasons, 12 of them as a player-manager. He also managed some in the 1950s, so in all, Hornsby spent some or all of five decades in the bigs.

Here is what he had to say about off-field sign-stealing in his near half-century of baseball: "Every team with a scoreboard in center field has a spy inside at one time or another."

1940: In his posthumously-published 1989 autobiography, Hank Greenberg: The Story of My Life, the Tigers slugger openly confessed to high-tech cheating over the course of two decades of his baseball career, which extended to front office duties after his playing days were over.

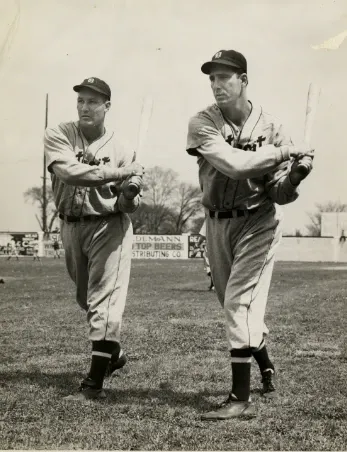

His confessions stretched back to 1940. In one of the dog days of that summer, pitcher Tommy Bridges, who had pitched the previous day, and injured third basemen Pinky Higgins chose to sit in the Briggs Stadium upper deck bleachers instead of the dugout. (Evidently a not-unheard of practice in those days.)

Briggs was showing his hunting buddy Higgins his new toy, a hunting rifle with a telescopic sight. Briggs pointed it at home plate and discovered that he could read the catcher's signals perfectly. (Evidently taking rifles into the stands of baseball stadiums and pointing them at home plate was also a not unheard-of practice in those days.)

Greenberg picks up the tale:

The next day we decided to test his (Bridges) ability to read the pitches and sure enough he sat up in the stands with Pinky. When the pitch was signaled for a fastball or a curveball, they had arranged a predetermined signal to relay it to the batter. It didn’t have to go to the coaches or the bench; it went directly to the batter. Strangely enough, you could look right over the shoulder of the pitcher and look out there in the stands and see the signal.

And so the Tigers, as an organization, acted: they called up a minor league manager whose sole job was to sit in the stands with a pair of binoculars, decode the signs, and relay them to the Tigers. Even when the stadium was packed, Greenberg said, his teammates could find their spy and see his signal. (Two players abstained: Hall of Fame second baseman Charlie Gehringer and Gerald Walker.)

Greenberg said that he and his fellow slugger Rudy York benefited the most from the scheme:

I think the record will bear it out. As I remember, between the two of us we hit one or two home runs for seventeen consecutive days during the month of September. Either Rudy would hit one, or I would hit one, or sometimes we would each hit two. I think it was picking up those signs that were instrumental in enabling us to win that 1940 pennant.

Well, nobody spins a tale like an old baseball player, unless it's a fisherman talking about the big one that got away. Luckily, thanks to the miracle of the Internet, you can verify these kinds of preposterous stories, so that is exactly what I did.

And you know what? Greenberg was full of it.

Actually, Greenberg and/or York's streak lasted only 15 days. However, that included two doubleheaders, so it did extend for 17 games. (Start on September 4 and work down.)

The Tigers won the AL pennant that year, edging out the Indians by a game and the Yankees by two.

And for the record, Greenberg believed those Yankees were also cheating. "It’s been rumored that the Yankees were stealing signs from their centerfield scoreboard for years. I know that they had a lot of success against [Cleveland Hall of Fame pitcher] Bob Feller. A lot of the hitters who didn’t figure to hit Feller had good records against him, and I’m sure they were helped by knowing what was being pitched to them.”

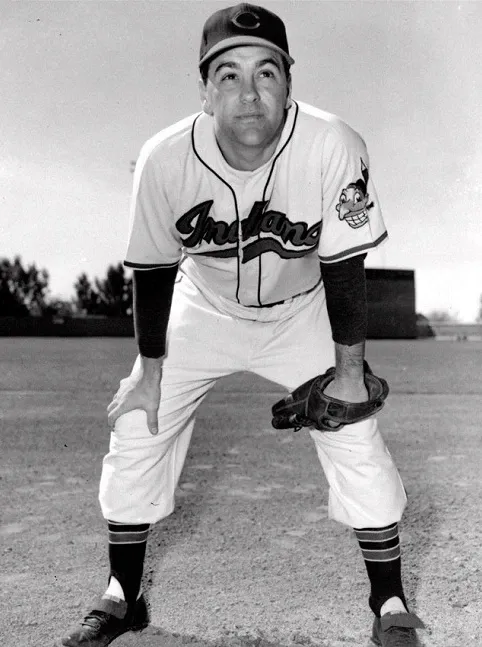

1948: After a hot start propelled to a perch atop the American League that lasted through the All-Star break, the long-suffering Cleveland Indians seemed to be losing their chance at their first pennant since their only one, in 1920. An August swoon saw them fall to third place.

What to do?

If you were Bob Feller, fellow Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Lemon, and two Cleveland groundskeepers, you set up an observation post in the center field scoreboard, enlisted the enthusiastic support of your player-manager (Hall of Fame shortstop Lou Boudreau), and let the batters know to look for an arm sticking out of a certain slot in the scoreboard if they want to know what pitch is coming.

That's exactly what they did, and the Indians went 19-5 over their last 24 games and went on to defeat the Boston Braves for the championship.

Word of this scandal got out in real time -- at one point, Red Sox manager Joe McCarthy pointedly glared at the scoreboard after Feller had signaled for an Indian batsman -- Hall of Famer Joe Gordon -- to swing away on a 3-0 count. Gordon jumped on the pitch and belted a grand slam.

All of America turned against the villainous Indians. Had their been a "baseball Twitter" in those days, it would have united as one and called the Tribe's trophy tainted. Instead of hanging their heads in shame, the Indians leaned into their role as the Heels of Lake Erie, mocking and taunting their opponents as whiners.

In 1950, Red Sox manager Steve O'Neill was still harping on about it, and once more laid into the cheatin' Indians in the public prints.

The Indians responded by sending him a gift bag that included a pair of toy binoculars.

1951: Using much the same tactics as the Indians, Bobby Thomson and the New York Giants' pennant-clinching "Shot Heard Round the World" was abetted by scoreboard spies.

Rumors about those Giants swirled in 1951 and for decades more, growing quieter with time. Fifty years later, as those Giants edged toward the Great Polo Grounds Beyond, a number of them unburdened themselves of the truth to Wall Street Journal reporter Joshua Prager in 2001.

As with Hank Greenberg, who admitted to a multidecade career's worth of cheating only in an autobiography published after his death, eternity has a way of teasing out truth.

1955: A veritable Who's Who of Sign Stealers pops up in a ridiculous fracas involving baseball espionage and surplus US Army materiel. The story begins in Cleveland where Lou Boudreau's Kansas City A's had just dropped a doubleheader to Boudreau's former team.

It's hard to con a con, as Boudreau came very near to proving in real time.

Acting on suspicions of scoreboard sign-stealing, Boudreau had his coaches his investigate "Feller's Roost" and his other old stomping grounds up there thoroughly.

While they found nothing exactly on those lines, they did come up with some promising intel: for some reason there were a few unused army trucks and jeeps stored on a grassy rise beyond centerfield, and in one of those jeeps was a telescope, and behind that telescope was a Cleveland reliever who kept that telescope trained on home plate during Indian at bats.

Ah-ha! It all became clear to Boudreau at once. This reliever, Boudreau snarled to bemused league officials, relayed pitch information to a second pitcher, who crossed or uncrossed his legs to denote fastballs and curves. Boudreau demanded the removal of the jeep and the telescope.

While the league officials deemed Boudreau paranoid, and probably believed, in any event, that all of this was pretty rich coming from one of the architects of the Indians tainted pennant of seven short years past, they heard him out and took his accusations to the Indians front office for an accounting.

And the Indians front office was was by then led by...

Hank Greenberg, he of the monster, sign-stealing-fed, pennant-clinching Detroit Tiger September of 1940.

"Simply preposterous," Greenberg laughed. Yeah, yeah, he agreed with the chuckling AL investigators. That Lou Boudreau is a raving paranoiac.

"We are not employing the Army Reserve Corps" concluded a chortling Greenberg.

Haha.

Except they were. They so totally were.

Eight years later, Al Lopez, manager of the '55 Indians, came forth with the truth: Boudreau's preposterous and paranoid ravings were 100 percent factual in every last detail.

But let's flashback to 1955. A few months after the Cleveland incident, Boudreau (was Lou short for Lucifer?) the victim found himself back in his old as villain: his A's stood accused of availing themselves of a surveyor's telescope from a construction crew at the Kansas City ballpark and installing it in center field.

1959: Chicago White Sox win the American League Pennant with aid from beyond the field. "We stole the signs from the center-field scoreboard," flatly stated our old friend Hank Greenberg, who by then moved on from the Detroit and Cleveland organizations.

1973: After the lowly Milwaukee Brewers batsmen took his Texas Rangers pitchers to the woodshed two nights in a row, Rangers manager Whitey Herzog believed there was funny business afoot. After a short investigation by his deputy, coach Jackie Moore, Herzog revealed his findings.

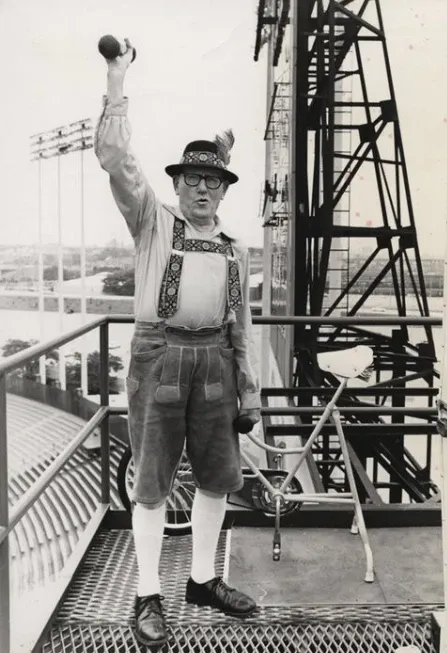

Out in the outfield, there were two men: one with a pair of binoculars, and the other in lederhosen and other folkloric German attire. This of course, was Bernie Brewer, Milwaukee's mascot, famous for sliding into a pretend vat of beer with every Brewer long ball. Herr Bernie, Herzog reported, would receive signal intel from the man with the binocs, and then reveal it to Milwaukee batsmen via a system involving hand-clapping and the donning and taking off of gloves.

After heading north to Kansas City, Herzog went on to accuse both the 1976 A's and Yankees of stealing signs with binoculars and relaying the info with walkie-talkies. Nothing has come out of Herzog's accusations.

Yet. But if we believe Herzog's accusations, and there are very good reasons to do so, then the Yankees' 1976 pennant is yet another tainted flag.

1980s: Tony LaRussa's Chicago White Sox had a flunkie in the clubhouse watching the game on TV, affording said employee a clear view of the catcher's signs on every pitch. He also had a toggle switch connected to a puny 25-watt light bulb on the scoreboard, and that seemingly faulty bulb tipped Chisox batters to expect fastballs or breaking stuff on every pitch.

2010: 110 years after pushing the high-tech cheating envelope, the Phillies got popped again, this time resorting to cliched old-school methods: binoculars in the bullpen.

And then in 2017, you had the Astros, Red Sox and Yankees. Numerous league sources have said that the practice is far more widespread than is generally known, and certainly more widespread than commissioner Rob Manfred wants you to know.

Historians of baseball cheating have uncovered so much they tend to get a little tired of writing about it, as they all generally adhere to the same general blueprint and vary only in small details.

Derek Zumsteg, author of The Cheater's Guide to Baseball, certainly succumbed to a certain ennui with his subject matter:

[It's all] variations on a theme, a Choose Your Own Adventure of cheating. A [hired spy / scrub player / coach / low man on the organizational totem pole] is placed [in the scoreboard / in a nearby apartment with a view of the field / in the stands / on top of the fence] and alerts the next batter to the next pitch using [ a mirror / the way they sat / an electronic device / opening or closing a hole in the manually-operated out-of-town scoreboard]...

Add to that cameras, iPads, and trash cans and you have the modern-day variant the Astros and Red Sox are being pilloried for.

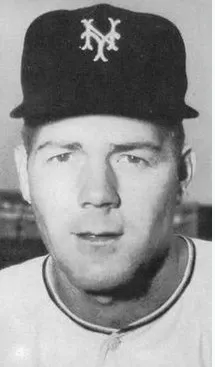

Perhaps as a sort of bizarro cautionary tale, Zumsteg brings in the tale of Al Worthington, baseball's lone Honest Man.

A devout Christian from Alabama, who had been born-again at a 1958 Billy Graham revival and would go on to coach baseball at Jerry Falwell's Liberty University, Worthington was dismayed enough by the binocular-aided sign-stealing of his own 1959 San Francisco Giants that he just couldn't take it anymore.

If they would just trust Jesus Christ, he told manager Bill Rigney, "they wouldn't need to lie or cheat in this world," and added that he would quit the team if they continued.

Rigney said years later that he called off the scheme. Maybe he did or maybe he didn't, but the fact is the Giants collapsed in the final week of the season and lost the pennant to the hated Dodgers, who no-hit the Giants in one game of a vital three-game sweep of their California archrivals.

Perhaps for that very reason, in 1960 the Giants shipped their goody-two-shoes malcontent off to the Red Sox, who handed him off to the White Sox within weeks.

There Worthington found himself working in what for him must have been something akin to the fires of Mordor: a Hank Greenberg-run organization where he was managed on the field by Al Lopez, the field general who commanded the Cleveland Indian army surplus caper that made a snarling madman out of Lou Boudreau.

Though Greenberg tried to sell Worthington on his situational baseball ethics, this was simply not an arrangement built to last. Worthington and his Lord and Savior weren't having it. He simply quit the team mid-season, and then wandered the baseball wilderness in the minor leagues for three long years.

“We tried to sell him,” GM Greenberg later said, “but the word was out that he was some sort of cuckoo.”

The Reds finally salvaged his big league career in 1963 and traded him to the Twins in 1965, where he finally found a home as one of baseball's top relievers for a few years. "But the biggest save I ever had was myself," he told a reporter. (He wasn't always such a cornball -- he apparently bore it in good humor when his Reds teammates gave him a pair of binoculars at a 1964 team party.)

Some sort of cuckoo. That's the label you got in the early 1960s if you didn't go along to get along in the pervasive atmosphere of cheating then rampant in the land. You have to suspect that all of baseball knew the real deal -- that Worthington was simply too honest to cheat, and thereby, by that very virtue, a clubhouse cancer.

And I refuse to believe that anything's changed since then, as the decade-by-decade timeline above attests. There are the Rules, and then there is the Code, and then there is the stuff beyond that everyone does themselves but pretends to be outraged about when it is done unto them. Witness the many hats of Lou Boudreau and Hank Greenberg, Hall of Famers both. As was Al Lopez. And Bob Feller. And Tony LaRussa. And Bob Lemon, and numerous players from the 1976 A's and Yankees, and the 1951 Giants.

Mike Fiers might soon find out that the consequences of the conscience he has decided to retroactively apply won't be universal acclaim and enhanced demand on the open market.

That's may not be God's honest truth, but it is the truth of imperfect man. The commissioner's office has known of these shenanigans for more than a century now and only takes action when it is forced to, and now technology has enabled both new ways to cheat and new ways to detect cheating. It is both easier than ever to break the rules and for opposing teams or even fans to expose that chicanery.

As the Philadelphia reporter summed up the "infernal device" brouhaha of 1900: This may be honest base ball, but the general public has nothing but contempt for people who play with marked cards.

Yep, but there is a contradiction inherent in that statement. Using marked cards is honest base ball, because everybody else really is doing it. And when everybody is playing with marked cards, who can be said to have the upper hand?

It's just another layer of the game. The early ballplayers had it right when they said signs weren't stolen so much as they were tipped. Codes and code-breaking.

Or to put it as simply as possible, if you are playing high-stakes poker against an opponent who waves his or her hand around with abandon, are you going to shield your eyes to keep it fair or take advantage of the gift your opponent has given you?

Oh, you're gonna look away, huh? I'll be sure to save you your busfare to the Al Worthington Christian Flophouse, home of the cuckoo nice guys, out of my winnings.

And yes, baseball teams that don't protect their signs or change them as often as necessary are either lazy or foolish. That's all there is to it. And baseball doesn't want you to know that truth because it doesn't think you can handle it. Time and time again they've poo-poo'd well-founded claims of rule-bending and conducted sham investigations in order to protect what they say is the integrity of the game.

Cheating is part of the integrity of the game.

That's the truth. It may not be God's honest truth, but it's the truth imperfect humans live with on this sinful planet.

Learn to love baseball as it is, not as you and Al Worthington wish it to be, because it is what it was in 1870, and it remained so in 2017, and it will remain that way in 2070.

John Nova Lomax is a cranky, middle-aged, Bayou City scribe / Gulf Coast Bullshitter. He speaks grackle and lives in a cabin on a river.