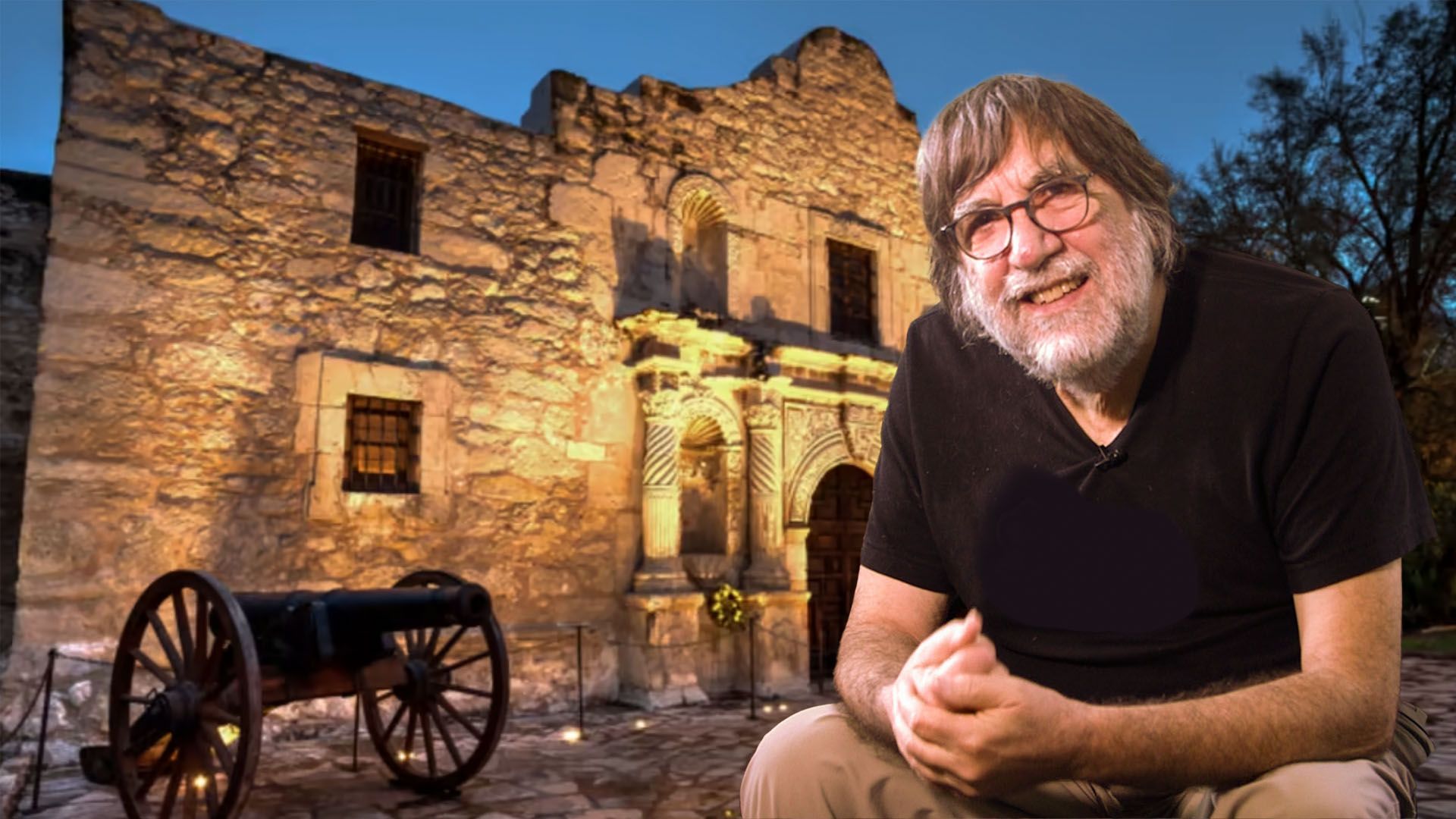

Texas Outlaw Writers' Podcast: Brian Huberman Remembers the Alamo

Here at Texas Outlaw Writers World Headquarters, we had decided to pause podcasting on a regular basis. Between day jobs, other projects, and writing the newsletter content, producing a weekly podcast proved to be a pretty big chore. Especially when it came to booking the A-list guests that we wanted to talk to, (and then getting this herd of Outlaw cats all together at the same time to record!)

But we want to leave the door open for special occasions. We keep the podcast account because we know that at some time or other, we will run into folks that we really need to interview. Folks we really want to talk to and hear their stories.

And Brian Huberman is one of those folks.

I have worked with Brian over the years in his role as a documentary filmmaker. He's a professor at Rice University, and he spends his summer breaks and free time producing his own documentaries and films. It keeps him in the game and allows him to pursue his art which he remains passionate about. His students benefit when he brings 'real-world-experience' to the classroom.

One of my fascinations with Brian is his fascination with us - Texans. Or probably more accurately, the historical figures of Texas history. A U.S. citizen, he spent almost his entire childhood in England. Yet Texas history (specifically the Alamo and the mythical heroes of the old West) is what fueled his imagination as a kid and has remained a passion throughout his life.

He certainly Remembers the Alamo, but he's worked on a variety of projects over the years. His website lists all manner of work. Brian was the cinematographer for Eagle Pennell's award-winning feature, Last Night at the Alamo (1984). And here are some of his documentary titles: Citizen Provocateur: Ray Hill’s Texas Prison Show, John Wayne’s The Alamo, Return of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Documentary, Sam Houston’s Retreat, The De la Peña Diary, and Who Killed the Fourth Ward?

I first met Brian when he was working on a project commissioned by the Holocaust Museum. He interviewed dozens of Holocaust survivors from this area about their experiences. With hours of those testimonials, he edited several films that can still be seen at the museum.

He's a guy who enjoys the process, enjoys the discoveries he makes, and enjoys the people he interviews.

My favorite Huberman story is how early in his career at Rice, "Easy Rider" star Dennis Hopper visited the campus. He came to show one of his own avant grade films at the Rice Media Center and talk to the students. His finale, so to speak, was taking the audience out to a local car race track and performing the "Russian Dynamite Death Chair Act." It's as absurd as it sounds... so listen to the podcast.

Here's some footage from that night. (The footage is pretty raw, it was first-generation video gear.)

From the YouTube link, a quote from the "Rice News" about the event...

"Dennis Hopper, at one with the shock wave, was thrown headlong in a halo of fire. For a single, timeless instant he looked like Wile E. Coyote, frazzled and splayed by his own petard. Then billowing smoke hid the scene. We all rushed forward, past the police, into the expanding cloud of smoke, excited, apprehensive, and no less expectant than we had been before the explosion. Were we looking for Hopper or pieces we could take home as souvenirs? Later Hopper would say blowing himself up was one of the craziest things he has ever done, and that it was weeks before he could hear again. At the moment, though, none of that mattered. He had been through the thunder, the light, and the heat, and he was still in one piece. And when Dennis Hopper staggered out of that cloud of smoke his eyes were glazed with the thrill of victory and spinout.'

A few clips from some of his films can be seen on his Vimeo account, (most are partial, some are low resolution.)

He continues his work and is still teaching. He is currently trying to complete a multi-part film on Geronimo. (He discusses this in the podcast.) He's got a list of projects in the works, and a few that he promises that he'll get to.

Author's note: A transcript of the podcast is below. It is a ROUGH, AI-generated podcast, lightly edited. I hope to post a video version of the interview in the near future. It will probably be raw and unedited.

You can listen to the podcast in the player/link above, or you can find it on your usual podcast provider. Subscribe to the Texas Outlaw Writers' Podcast (on your provider.) Most providers will alert you to any new release.

Transcript below.

Brian Huberman (00:00:11):

I'm a professor of, they've changed the name of the department just the other day. So now I am a professor of art.

Chris Newlin (00:00:19):

Are you serious?

Brian Huberman (00:00:20):

That's, that's what, and within that, of course, my, my area of art is what you might call loosely film.

Chris Newlin (00:00:30):

Cool. So, well, let's start with, um, y you're as British sounding as anyone I know, but you were born in the US as a US citizen, right? So yeah. That's, talk about how that happened and what, where you grew up.

Brian Huberman (00:00:43):

I was born in New York, actually. I was born in Queens. That's, I guess we should be specific. And, uh, uh, my mother was English. My father is an American from New York. Uh, they met in England during World War ii. My mother was a war bride, and, um, they went back to, uh, New York during the war. My father was invalid home. And, uh, and she went along too. And, uh, I, I was born in New York and, uh, and lived there until about the age of three when, because my father could not make a living

Chris Newlin (00:01:47):

Right, right, right.

Brian Huberman (00:01:48):

And, uh, unti l he got held up and, uh, as a result of being held up, he, uh, he, he, he started peeing blood and decided that it was time to find greener pastures,

Chris Newlin (00:02:16):

And mom was cool with that.

Brian Huberman (00:02:19):

My mother. Mm-hmm.

Chris Newlin (00:02:36):

So you were educated in Great Britain, right? Yeah. Where did you, where did you land in, in England?

Brian Huberman (00:02:41):

Um, my, my grandmother lived in a town called Tunbridge Wells, which is in Kent, which is southeast the county, and very southeast England called a home county because it's, its connection to London closeness. And, uh, so Tunbridge Wells is, is, uh, is a bath town. That's where in the 19th century, uh, people would go there to enjoy the waters. Oh, okay. It would be that kind of a cleansing type of place. And, uh, it, it, it, it, uh, the vibe of Tunbridge Wells still has that quality of, uh, I don't know, a kind of a, some, a place out of time. Somehow it, it, it's sort of strange. Um, so that, that's where we lived for the, for, for initial period of time. And, uh, uh, until they've kind of figured out a place to buy a house near it to London in the kind of the commuter type of situation.

Chris Newlin (00:03:50):

And what did your dad do?

Brian Huberman (00:03:52):

Well, he, he, um, he ended up as a car salesman.

Chris Newlin (00:03:57):

Okay.

Brian Huberman (00:03:59):

But, uh, at that time when he was went to England, uh, he, uh, he was invited to, uh, take over this factory that made hats. You know, my father comes from a kind of a Jewish New York tradition, the garment district, and all, you know, the, this is in his blood. And, you know, blocking hats was, remember, hats are bullshit today.

Chris Newlin (00:04:26):

Right, right, right.

Brian Huberman (00:04:27):

But, um, uh, uh, they're a novelty. But at the time, I'm talking about a standard wear, uh, late forties, early fifties. Ah, everyone is wearing a hat. It's a serious bit. Men and women. Right. You could, uh, if you are involved in millinery, millinery business, that's a serious damn business at that time. And so, being invited to go to England to, to, to kind of take over more or less start this factory and hats was, uh, you know, felt like a big deal, except that when he got to the factory, which was somewhere in the east end of London, um, it was just a, a dusty cobwebby, uh, building. And all the machines were rusted. And it hadn't been m used forever. It was a complete disaster. And, uh, but anyway, he, he moved into something or other after that, but it was, uh,

Chris Newlin (00:05:31):

Brian Huberman (00:05:35):

Who me? Yeah. Um, I guess so. I, I, you know, I I,

Chris Newlin (00:05:43):

Your typical school boy, you

Brian Huberman (00:05:44):

Yeah. I went to what's called the direct grant school. It's not quite a public school, but it's like that. Okay. Remember in the, in England, public and privately, it's, it's all different. Uh, you know, public schools are not what you think of here. Um, public school is, uh, is sort of, uh, uh, uh, kind of an aristocratic kind of edge to it, you know, Eaton and places like that. Right, right. Are, are so-called public schools, state schools are, you know, and I was sort of somewhere in between anyway, so you were actually part, I went to a school called Elton College from the age of eight, I think, until I was 16. It was a big, and, uh, it was a school founded as a school for the sons of missionaries. Oh yeah. It was a strong, uh, Christian, um, kind of bent to it.

Brian Huberman (00:06:47):

We had a great chapel at, uh, I'm always amused here in this country cuz everyone sort of like knives out and, um, kind of throat cutting about the issue. Should there be prayer in schools or not? And, um, fuck! I went to a school where we had a gigantic chapel, beautiful building covered in vines and stuff. That's what greeted you as you entered these great grounds, filled with plane trees and so forth. And every morning, the entire ensemble of that school, several hundred people gathered in that chapel. And we sang songs, William Blake, Jerusalem, very moving, very moving to have, you know, a couple of hundred voices, uh, you know, con contributing to that and, and somebody reading a lesson for the day. There's a kind of a, an an epic Charleton Heston sort of, uh, quality to it because, you know, religion isn't something to be talked about or thought about.

Brian Huberman (00:08:00):

It's to be experienced. Right. And, uh, that's what we had going there. And of course, no one thought anything of it. Right. You know, as you walked out of the chapel after that, it was gone. You know, there's no way, you know, I'm a, you know, a happy, uh, atheist I suppose, you know,

Chris Newlin (00:08:19):

so it took religion has it really took!

Brian Huberman (00:08:20):

it has no part of my life really. And, um, uh, and yet I had a full religious sort of, uh, supported, uh, background. It obviously didn't do me any damage, I don't think. And, uh, so, so it was a, a, a rich school experience. We played rugby, not soccer. Right. That tells you that that's, uh, there's a hierarchical step there. Rugby is for cavalry offices. You know, soccer is for cannon fodder you know, it's that, uh, that's

Chris Newlin (00:08:58):

So on that, on that very, very strict British status and class system. Um, you were, you were in the middle then you sort of carved out, your folks were sort of carved out a little position in the middle.

Brian Huberman (00:09:12):

In the middle, sorry, in the middle of, in

Chris Newlin (00:09:14):

The m iddle of the class system. Oh, I see. You weren't on the bottom, but you weren't quite No,

Brian Huberman (00:09:18):

We were

Chris Newlin (00:09:18):

At Eaton.

Brian Huberman (00:09:20):

No, right.

Chris Newlin (00:10:14):

Right.

Brian Huberman (00:10:15):

And, um, and they were proud of it. Fuck you! You know, that's, and uh, and, and often were incredibly, um, loyal to, to institutions like the monarchy

Chris Newlin (00:10:31):

And still are, I

Brian Huberman (00:10:32):

Mean, and probably still are, you know, that, uh, that, uh, it's not that they had any aspiration for, there's no upward mobility. It's almost like a feudal order. You have the working classes born into that class and proud of it. And then at the higher end is the aristocracy, including the monarchy and landed gentry and so forth. And, and they understand where they are. And, uh, there's no way, there's no way into those, right. You're either born into,

Chris Newlin (00:11:04):

They keep in your place.

Brian Huberman (00:11:05):

Right. But the, the, the wackos are the middle class in between because they somehow have, uh, absorbed the, the, the myth of upward mobility, the possibility of achieving some kind of alternate position.

Chris Newlin (00:11:25):

And you, you, you embrace that wacko. Well,

Brian Huberman (00:11:29):

I'm being in the middle class, I, I'm sort of stuck with that Right. With, with that, uh, understanding of trying to always trying to better oneself. So, and always kind of really never unfi understanding yourself. Right. And in that sense, the working class and the aristocracy are, are, are calmer, more settled and, and are often idealized in, in, um, in, in entertainment shows. Mm-hmm.

Chris Newlin (00:12:11):

The sort of, the grapes of wrath will, they'll, the will always be the people when it

Brian Huberman (00:12:15):

Well, yeah, that's that. That's right. Exactly. Well, there, there you have it. They, they, they're kind of, people

Chris Newlin (00:12:20):

Will keep coming.

Brian Huberman (00:12:21):

I guess we would call them blue collar. Right, right. Because it's America. We didn't,

Chris Newlin (00:12:25):

So how'd you get over here? How'd you get back to the States?

Brian Huberman (00:12:29):

Oh, um, my late twenties. Um, you know, I went to art school in England, an act of desperation.

Chris Newlin (00:12:42):

Because, because you were lost or because

Brian Huberman (00:12:43):

Yeah, I was lost.

Chris Newlin (00:12:44):

It was the last hope.

Brian Huberman (00:12:45):

I just didn't know what to do. And, um, I, I, uh, I, I thought about, um, coming back here to, to, to the United States. Maybe I would find something here, but the Godamned Vietnam war was going on, and, uh, I didn't need to make myself

Chris Newlin (00:13:06):

Available

Brian Huberman (00:13:08):

any more vulnerable to that than I'd already been drafted in England. But they sort of ignored me because I was in England. And, uh, so going in, oh,

Chris Newlin (00:13:19):

You were drafted by the Americans while you were in England? Yeah. Because you had a dual citizenship, or

Brian Huberman (00:13:23):

I'm not dual. No, I'm you're

Chris Newlin (00:13:25):

Old. At

Brian Huberman (00:13:26):

That time, you couldn't get a dual citizenship,

Chris Newlin (00:13:28):

So you were US only

Brian Huberman (00:13:30):

Yeah, that's right. I made that when I got to be 21. I got to make a choice. I go either Brit or American. And at that time, I had this sort of romantic notion about, about, uh, the United States,

Chris Newlin (00:13:47):

Silly you

Brian Huberman (00:13:49):

And, uh, so I opted for that. And so bingo. You know, anyway, you know, I'm, I'm imperiled by kind of things like, uh, war service and, uh, that, that actually seemed quite kind of interesting to me. Thank God I kind of got over that. And

Chris Newlin (00:14:12):

I guess so.

Brian Huberman (00:14:12):

Well, you know, that's what happens.

Chris Newlin (00:14:14):

The romantic notion

Brian Huberman (00:14:15):

Of the young full of young guy, because it's an adventure, I suppose. Right. And, uh, so I can't, I, I had a little tinge of that. I want to go and see what that's like.

Chris Newlin (00:14:26):

Whew.

Brian Huberman (00:14:26):

Chris Newlin (00:14:27):

Brian Huberman (00:14:32):

You No, I went to art school. And when I was the middle of art school stuff, which began to feel like, this is what I want to do, this feels good. Then I discovered a filmed movie camera, a

Chris Newlin (00:14:54):

And that was it.

Brian Huberman (00:14:55):

So I started shooting with that, and yeah, that really began to kind of got, get my interest going and

Chris Newlin (00:15:03):

The, the Young Spielberg story.

Brian Huberman (00:15:04):

And, um, and then the National Film School opened and, uh, this was like a government fueled operation. Oh, wow. And, uh, it was a big fucking deal, kind of industry supported. Although they hated it.

Brian Huberman (00:15:23):

They hated it.

Brian Huberman (00:15:24):

Chris Newlin (00:15:28):

apprentice System

Brian Huberman (00:15:29):

The Yes gov Yes gov, yes gov, you know, all that kind of commy inspired bullshit. Yeah.

Chris Newlin (00:16:14):

Right. So, but I don't recall Britain having the film scene of a forties, fifties Hollywood.

Brian Huberman (00:16:24):

No. We've had great studios, the Eeling studio films

Chris Newlin (00:16:28):

Of, there you go.

Brian Huberman (00:16:28):

You know, there, because I'm there is a great British fan, a great documentary tradition. I mean, it, it, it's big. But, um, the, the feeling was, you're right, the other guys are getting away from us. And, uh, the only way we're going to, you know, develop our scene, our film scene, is to put some money into it and gonna actually make a, a step in that direction. And it was a big step for them, because I discovered I was one of the first students in the first bunch. There were 25 of us. Wow. It was, uh, it was, uh,

Chris Newlin (00:17:08):

The great hope of the British film war.

Brian Huberman (00:17:09):

It, it was, I mean, I just squeaked in I know cuz uh, some of the people that, one of the other students was Bill Forsyth, the Scottish filmmaker who made, uh,

Chris Newlin (00:17:21):

Local Hero

Brian Huberman (00:17:21):

Local. Yeah, exactly. I mean, there were people there that knew what they were doing, you know? Yeah. Were serious players even at that point. And, you know, I had a, a home movie that I'd made about the Alamo, you know, it

Chris Newlin (00:18:01):

Wrong on so many levels these days, you would be, uh,

Brian Huberman (00:18:04):

Chris Newlin (00:18:26):

Mel Brooks makes the Alamo

Brian Huberman (00:18:36):

Gradu, I graduated, uh, at the film school in 74. And, uh, I was doing odd jobs, mostly assistant editor, Fuck. what a misery that was. I mean, you know, this is assistant editing, you know, in a film editing room. You know, what a fucking nightmare that is. Keeping track of all the Yeah. Where are the tiny trims, the scene, blah, blah, blah. Yeah. You know, my, my best moment, uh, in, uh, working as a assistant editor, I was on a production for, for somebody famous, I can't think of his name,

Chris Newlin (00:19:24):

Don't

Brian Huberman (00:19:24):

Remember the title of the film was Forbidden Image. And it was about the erotic art of, uh, ancient India as seen in the temples and so forth. Okay. Okay. And it was, uh, it was a lovely little film. And the big plus was they got Ravi Shankar to do the music.

Chris Newlin (00:19:43):

Oh, how cool.

Brian Huberman (00:19:44):

And so, um, yeah, I'm there standing where you do you stand in the back, you know, with the racks, um, when the great one came in. And so I got to witness him being shown the various cuts, dailies or whatever that he was gonna have. Well, they had the film edited already. Oh, wow. He was brought in at the end, and this is the bit you'll fill in and this bit and this bit. And then I got to go to the recording studio at emi, wherever the hell that was.

Brian Huberman (00:20:15):

And, uh, and film them recording the sound. And he arrived with all his crew, his band, and they were like a bunch of Indian gangsters,

Chris Newlin (00:20:34):

George Harrison.

Brian Huberman (00:20:35):

spritual kind of Yeah. Kind of floaty, kind of wonderful kind of thing. And he arrives with his and his orchestra all wearing kind of gray coats and, and, uh, you know, smoking, roll up cigarettes and, and you know, they're just tough guy session men. Yeah. Just as you only they're Indian

Chris Newlin (00:21:12):

So, um, you mentioned the Alamo, your very first film as a kid was on the Alamo. You've had a lifelong fascination Yeah. Passion infatuation. I know. And I guess the comparison would be, we all know Phil Collins kind of had the same thing. And that's your generation, I suppose. Yeah,

Brian Huberman (00:21:31):

It's the same. Well, because

Chris Newlin (00:21:32):

So what, what did that stem from? It's

Brian Huberman (00:21:34):

Walt Disney. Clearly, it's, there's, uh, and you know, if you're at the right age, a hero figure can just set you off. You know, I, I think that's

Chris Newlin (00:21:47):

So John Wayne, was it?

Brian Huberman (00:21:48):

No, it was Fess Parker.

Chris Newlin (00:21:50):

Fess Parker. Okay.

Brian Huberman (00:21:51):

Okay. It was Walt Disney. Okay. No. And, uh, that was 55, 19 55. And, uh, and then, you know, five years later, Wayne comes out with his and it just sets it,

Chris Newlin (00:22:07):

The hook is set.

Brian Huberman (00:22:08):

Well, I think so. I think, you know, because, you know, Wayne's film was so real. It was real, you know, he built a real place for, you know, it's still out there in Brackettville. Right. Moldering away now, I guess, sadly. Um, uh, but yeah, that, uh, and then don't forget, the fifties was total Western, Western Western, Western. And, uh, and I was at a tender age when John Ford's westerns were being released on English television. Uh, I have no idea how or why, but they just were. And so I was overwhelmed with

Chris Newlin (00:22:54):

And, and did you

Brian Huberman (00:22:54):

Stuff. And as you see, I'm remember, I'm a disconnected American. I'm living in England, and I know that I'm American, and my father is clearly that, cuz he sounds like a New York tough guy. You know, he's a, and, uh, but I have no idea what that really is. It's this sort of mysterious other place that's

Chris Newlin (00:23:17):

On the screen.

Brian Huberman (00:23:18):

And, and, and this is the expression of it. Here it is. And it's all horses and dust and killing Indians.

Chris Newlin (00:23:26):

Brian Huberman (00:23:29):

Yeah. I mean, genocide, because I didn't think of it in those terms. Of

Chris Newlin (00:23:33):

Course. And so at what point do you think, in your mind you went, I'm going there, I will remember the Alamo. I will.

Brian Huberman (00:23:42):

Oh, well, I, yeah, I guess I always was. I mean, I, because, uh, everything I was working on always seemed to look in that direction. And, uh, I guess it was inevitable that I would wind up him, but that, that I would end up in Texas is a bit of a joke. But,

Chris Newlin (00:24:02):

Well why so, I mean, well,

Brian Huberman (00:24:03):

It was too good to be true, isn't it? And I made no effort

Chris Newlin (00:24:08):

To Oh, it was just happenstance. You went in. It

Brian Huberman (00:24:09):

Just happened. No, I, I had graduated the film school. I told you I was doing these odd jobs, and then all of a sudden I'm offered the job to come and teach here at Rice because the film school mafia at that time was all very, the, the head of my English film school was very much connected with the de Menils who had founded the Media center.

Chris Newlin (00:24:34):

And for our viewers, listeners, the de Menils were one of Houston's wealthy benefactor families. Oil money. They developed the Menil collections and art galleries and exactly the Roth Rothko Chapel. And they decided they were gonna be your benefactor as well, or the Rice benefactor?

Brian Huberman (00:24:51):

Well, the Rice, yeah. They, you know, they built, uh, they brought the art department from St. Thomas, university of St. Thomas, which is here in Houston to Rice University. Uh, I think there was a kind of a split in wave between the Jesuit fathers and, and the Menils about how things were going to go. And, uh, the media center, particularly for the study of film with the idea that a grand idea, a grand vision about film, that it was a, a unique medium for our time that they call it the Media Center. Because film, in their eyes was a, a medium, a vehicle to carry the important information to a society or to a democratic society so that they could make valid moral choices. Like when they vote about, about the world in which they wanted to, to, to live in, but without being informed, without the right information, how could they make a right, uh, decision. So the vision of the Media Center, where I was brought into, was that we would mediate between the, the, the, the knowledge that people have in a great university and the, the people out there that don't have access to it, and how should they get access to it? Well, film is the vehicle to kind of make available so be popular. That kind of, that was the vision. That was the vision.

Chris Newlin (00:26:26):

And so you were very simpatico with what they were doing and Well, like

Brian Huberman (00:26:30):

In, in, in the sense of, uh, being a documentary filmmaker that, I mean, absolutely. Documentaries now kind of cover a whole span of things. Most of it's just light, light entertainment seems to me. Bullshit.

Chris Newlin (00:26:46):

Right.

Brian Huberman (00:26:47):

Um, but, uh, uh, you know, at the other end, there, there has always been, I think in the arts and certainly in filmmaking, you know, an area where people really are trying to do something important and interesting. And, and, and that was the area I wanted to be in that, that area.

Chris Newlin (00:27:07):

Right, right. So, while we're there, while we're there on the opening of the school, I was gonna say this for later, but I just can't let it go. There was, it was a big hullabaloo when they opened. I mean, they were very, this was a big to-do for rice and for the town. And, and it seems like, was there a grand opening, or, what I want to get to is one of the big invited guests was Dennis Hopper and, and, and other celebrities came by, or what's

Brian Huberman (00:27:34):

The Well, yeah, but that, yeah, I think you're confusing if you,

Chris Newlin (00:27:37):

okay. All right.

Brian Huberman (00:27:37):

A few event, I mean, I wasn't here when the building opened. Oh, okay. That was 1970. And, uh, I think Andy Warhol came.

Chris Newlin (00:27:47):

Wow.

Brian Huberman (00:27:47):

For that. Cuz the Menils underwrote Andy Warhol.

Chris Newlin (00:27:52):

Geez.

Brian Huberman (00:27:52):

At least at some stage in his, uh, in his, uh, working. And, uh, anyway, he, he was there and I, I think there was a big, there was a big, I mean the arrival of film, cuz I'm just looking at that angle of it. There was, you know, a lot of people changed their direction and included film in their studies or in their work. I mean, there was a, you know, uh, a big hope for that. So I think the, the, the, the Manila's, uh, presence, you know, was, was big. But you mentioned Dennis Hopper. Now we have to jump forward to 1983. Oh,

Chris Newlin (00:28:36):

Okay. So,

Brian Huberman (00:28:37):

And, um, Dennis said, now I was here for that

Chris Newlin (00:28:42):

Brian Huberman (00:28:46):

No, he, he invited himself

Chris Newlin (00:28:48):

Brian Huberman (00:28:51):

Chris Newlin (00:28:59):

to say the least.

Brian Huberman (00:29:00):

Yes. I mean, in terms of his, uh, some people might think of him just as some whacked out actor in movies, but of course he was a filmmaker, but he was also an art collector and, uh, a self-destructive drug abuser. And, you know, at various times. And, and, uh, and he was all of those things at the time I met him. And, uh, he, he had a need at that particular point to, um, do stuff in art and, and to, and somehow or other, and I don't know why he winded up, um, approaching, uh, us at Rice to do it there. Uh, uh, I'm not, I remember the first time he, he came to the media center, uh, he was working on a film and just happened to be in town

and asked if he could come and just visit.

Brian Huberman (00:29:55):

I guess he was already planning a possible event there. So I agreed that I would wait for him to come. We were showing a movie that night in our auditorium for our public screening called Taxi Driver. And, uh, yeah, I'm, so I'm standing in the film booth while this film is going on. At some point during the film, there's a knock at the projection room door, which was an outside door. And, uh, we opened it and there he was with several suitcases,

Brian Huberman (00:30:44):

So he brings, we bring all this crap into the projection booth and, uh, he's pretty high energy and anyway,

Chris Newlin (00:30:52):

or at least high.

Brian Huberman (00:30:54):

And, uh, anyway, he looks through the projector on Windows and sees Taxi driver being projected. And so, uh, that, that, uh, transfixes him for a bit. And he starts narrating the film in the sense, uh, loudly, uh, explaining how he had been offered some part in it or some, some kind of backstory that of his involvement. Anyway, he's, but really loudly so that I could see that the people in the audience were kind of wondering what, what this other voice was going on. Um, anyway, uh, then because he was there and we had this group, uh, out this big audience, this, I said, I just heard myself inviting him to go and speak to the audience, like, about nothing and anything, you know, after the film, if he would like, he said, yeah. Yeah.

Chris Newlin (00:32:22):

Um, uh, and he was already a, a star by then. “Easy Rider” is under his belt.

Brian Huberman (00:32:28):

Yeah. 1983.

Chris Newlin (00:32:29):

Oh, oh my God. Yeah.

Brian Huberman (00:32:31):

No, this is, uh, deep in, so he's just sort of crazed. That's all. I mean, going through emotions so rapidly. Um, anyway, we get down the front and, uh, so I gotta do my best to introduce him. And I was trying to think how the, fuck, what, what do I need to say something? And, uh, and the only film I could think of

Chris Newlin (00:34:13):

Brian Huberman (00:34:16):

It was hilarious. It was hilarious. But he was, uh,

Chris Newlin (00:34:20):

It was a show.

Brian Huberman (00:34:21):

Yeah. He was a a a extraordinary kind of, uh, ball of energy. I guess that would be putting it politely. Well, so

Chris Newlin (00:34:32):

Speaking of Ball of Energy, I, of course, I want this to go to the, the famous Russian Dynamite Chair trick.

Brian Huberman (00:34:38):

Well, that's what.

Chris Newlin (00:34:38):

and what the hell?

Brian Huberman (00:34:39):

Well, that's it. He, um,

Chris Newlin (00:34:42):

Was that that trip or later?

Brian Huberman (00:34:43):

No, uh, that if, if the, the True Grit thing was like a wrecky. And, uh, then he kind of arranged, uh, and it was a connection with the, uh, with the Menils. Sorry, is that No,

Chris Newlin (00:35:01):

No, go, go, go,

Brian Huberman (00:35:02):

Go. It was, uh, I think, uh, the thing was set up, uh, in connection with the, the Menils. So

Chris Newlin (00:35:10):

He actually arranged that with the Menils?

Brian Huberman (00:35:13):

Oh, yeah. No, it was a, it was a big deal. His coming in. It was, uh, he, we had, uh, we showed films of, of his and his latest film, which was Out of the Blue or something like that. Uhhuh

Chris Newlin (00:35:53):

His film.

Brian Huberman (00:35:54):

Right. And then he did an avantgarde, that's the best way for me to put it, performance at the media center where he showed a series of videos and clips. And he was in the classroom with a video camera on him. So he never actually presented himself to the audience, but we could flash him up on the screen at times. So it was a whole kind of strange, off the cuff kind of mm-hmm.

Chris Newlin (00:36:57):

To some kind of car speedway, butA race track Speedway out

Brian Huberman (00:36:59):

off, uh, 45 kind of way out there somewhere. Right, right. Hopper Road. It was off. Yeah. He was mused by there, it was Off Hopper Road. And then we drove on, uh, onto the speed track and the, the events of that night were just ending. And so the, the, the whole place was filled with cowboys, you know, big hair, all that Texas blue collar shit. And, um, we drove into the center. It struck me that we were a bit like the Christians being brought out to feed the lions. And we were the, like the final act

Chris Newlin (00:38:04):

Was a chair with four or five sticks of dynamite under the seat or

Brian Huberman (00:38:09):

Something. I don't know. I don't know where. I couldn't see.

Chris Newlin (00:38:12):

And he was either gonna sit on it or get under it.

Brian Huberman (00:38:14):

He, it seemed to me that he was crouched.

Chris Newlin (00:38:17):

Right. I saw the pictures. Right.

Brian Huberman (00:38:19):

Yeah. He was crouched and I thought the dynamite was around him or something. Oh,

Chris Newlin (00:38:24):

All

Brian Huberman (00:38:24):

Right. I, I'm not sure. Anyway, it went off

Chris Newlin (00:38:28):

And, and you were filming

Brian Huberman (00:38:29):

This? I, yeah, I think so. And

Chris Newlin (00:38:31):

What was your state of mind that you're out there with some sticks of and Denn is Hopper?

Brian Huberman (00:38:37):

I don't know, it was just sort of a, he'd been around for days, so I'd been filming him on and off for days and, uh,

Chris Newlin (00:38:45):

With a big old threequarter deck and a

Brian Huberman (00:38:47):

Big old heavy beta

Chris Newlin (00:38:48):

Cam

Brian Huberman (00:38:49):

Had shit. We had shit, it was, that's why the shot is, uh, the shot is so bad, unfortunately, cuz actually, I think my students shot that.

Chris Newlin (00:38:59):

Well, there's two, there's two V views of it. And you shot one, and then somebody else shot another.

Brian Huberman (00:39:05):

Yeah, there are two views, I'm not sure.

Chris Newlin (00:39:07):

And and you said, and Werner Herzog was there, is that right?

Brian Huberman (00:39:11):

No, no, no, no. It was

Brian Huberman (00:39:14):

Wim Wenders and Terry Southern, he was there.

Chris Newlin (00:39:17):

Okay.

Brian Huberman (00:39:17):

Okay. And, uh,

Chris Newlin (00:39:19):

But at, at, at some point, you're out there and you're rolling. Is there any thought in your mind where we could all blow up

Brian Huberman (00:39:27):

No, I didn't think that at

Chris Newlin (00:39:29):

All. Okay. All right.

Brian Huberman (00:39:30):

I don't know why,

Chris Newlin (00:39:31):

But did you think that Well, he could blow up because this is insane.

Brian Huberman (00:39:34):

I don't know. I it's kind of, it, it's funny, you'd think, you know, rice University thought that cuz uh, he wanted to do it at the Rice car park originally.

Chris Newlin (00:39:46):

Oh gosh.

Brian Huberman (00:39:46):

And they said, dynamite

Chris Newlin (00:40:11):

And she's hanging onto you while you're walking around at the, Oh my gosh.

Brian Huberman (00:40:13):

Exactly. It's kind of, I I must have been insane because there was a policeman on horseback.

Chris Newlin (00:40:21):

I remember that.

Brian Huberman (00:40:22):

At least one. I mean, uh, who was not happy with all the craziness, you know, so anything could have happened, you know, it, uh,

Chris Newlin (00:40:31):

but it worked. It,

Brian Huberman (00:40:32):

yeah. I mean, Hopper was, uh, appalling at that point, uh,

Chris Newlin (00:40:38):

In terms of

Brian Huberman (00:40:39):

His behavior. He was, uh, there was a, an ugly side to the man and, uh, it just came out when he was, uh, you know, abusing, uh, whatever the fuck he was doing. And, um, uh, he had a woman, a young woman assistant who was very pleasant. And he was so ugly to her. It was, uh, you know, there's no glory in there

Chris Newlin (00:41:29):

There you go.

Brian Huberman (00:41:30):

The last holdout, I filmed him in an office where they're selecting, um, music to use in that abstract performance. And, uh, and, uh, and I'm filming and he's aware of it. And it doesn't particularly care for the, and it's

Chris Newlin (00:41:51):

For your presence.

Brian Huberman (00:41:52):

No, exactly. But he, he can't tell me to leave. But I don't know why he could, I mean, but, uh, that, that's an interesting insight into his character. And it's there that you can see him bullying this young woman. Uh,

Chris Newlin (00:42:09):

That's terrible. So, let's go back to the Alamo a little bit. Um,

Brian Huberman (00:42:21):

You mean John Wayne's Alamo or the,

Chris Newlin (00:42:24):

The San Antonio Alamo

Brian Huberman (00:42:26):

It's hard to know which is the real Alamo.

Chris Newlin (00:42:28):

That's true.

Brian Huberman (00:42:30):

Or is it the one in sinking Springs? Yeah. Um, well, it's, it's like arriving at Mecca or something like that. Yeah. If you're a fan, you know,

Chris Newlin (00:42:43):

But, but I remember as a boy, it was, it was already then, and this earlier than this period when you probably saw it, it was already the shrine. It was already in the middle of San Antonio, right along the city streets. Yeah. And it sort of lost its luster for a child to see. Oh,

Brian Huberman (00:43:02):

There's no, but by the time I saw it, I guess I was not a child.

Chris Newlin (00:43:06):

Right, okay.

Brian Huberman (00:43:07):

I was already in my twenties and, uh, you know, so I had read enough about it. I knew the history of the building and what was lost and, and, and all of that. I, I, I guess I was prepared, uh, for that. And also, I, I remember I was prepared because I had encountered people like yourself who'd seen it, and, and had kind of, right. I remember meeting this, uh, this girl on a transatlantic steamer and, uh, in 1967 I think it was. And, uh, I was talking, you know, we wound up talking about that. And she said, oh yeah, cuz she'd been to San Antonio, the Alamo, a little clay fort downtown

Chris Newlin (00:44:03):

Hmm.

Brian Huberman (00:44:04):

Well that's

Chris Newlin (00:44:14):

Well, well, and you're an academic, so look, you've, you've studied your whole life, the Alamo. Yeah. And you are, at some point in your young adult life, you are able to start separating the myth and the legend from the real Alamo, the real story. Sure. And, and yet you remain fascinated with that myth. Talk about that.

Brian Huberman (00:44:36):

Well, cause the myth kind of changes and expands and alters. It's only for the idiots that it becomes like an ideological kind of form, which never changes, which is ugly. And, you know, and I know that, that, uh, not, not that long ago, within the year when there was some kind of trouble, uh, I forget what trouble in our troubled world, but all of a sudden in the press, there was this photograph of all these wackos, you know, looking like the proud boys. They weren't the proud boys, but they looked like them with all these outfits that they wear, you know, with them sort of defensive jackets and hat. And their ar fifteens were all lined up in front of the Alamo going, they shall not pass. You know, they're, Fuck you! This is, you know, we're killing everybody, you know? And, uh, I thought, this is, uh, this is not what that represents. Not to me, at any rate, not to me. And that's the problem. So much of our history has been appropriated.

Chris Newlin (00:45:53):

Brian Huberman (00:45:59):

Hello.

Chris Newlin (00:46:00):

Take pause. But for, okay, I'm rolling again. So, but for some people that they can't separate that mythology, was that difficult for you? Or have you always been a academically minded and, and I

Brian Huberman (00:46:12):

Dunno if it's being academic, but, uh, I think it's, uh, it's much more basic than that. Uh, um, it, it's, uh, the ability to be able to, to have the freedom to play with these things. You see, as a child, I was introduced to with toys and, uh, play was incredibly revitalizing and learning experience, I think. But, uh, play to play requires, you know, as I said, kind of a sort of freedom with the material. I mean, literally, uh, it's fun to watch kids, they play with blocks or whatever. They build a structure, well, bam, down it goes, you know, because they're not locked into it. If you are locked into, it becomes an ideology. It's devils. It's awful.

Chris Newlin (00:47:06):

And that's almost,

Brian Huberman (00:47:06):

And that's what I see in those monsters with their ar fifteens standing in front of that, that, that building that I think they have no understanding of the, the, you know, of what they, they just think it's about death. That's death. They are, you know, they are about death. What's that wonderful line from the psalms? You have made a covenant with death and with hell. You are in agreement. You know that, that's what those fuckers are about. And it's, uh, I, I'm about life. The, the Alamo is a life experience for me. You know, it's in, in, it's in, I've connected with it throughout my entire life. It's not a death trip. Not to me.

Chris Newlin (00:47:52):

And that's funny, you quoted the Psalms and you went to a school where religion was a huge component, yet it shaped you. Yet you, you, yeah. You're not loyal to those. They're

Brian Huberman (00:48:03):

Very, very,

Chris Newlin (00:48:03):

That doctrine

Brian Huberman (00:48:04):

We're just a lot of contradictions. Right.

Chris Newlin (00:48:07):

But that's the good contradictions. That's the good.

Brian Huberman (00:48:09):

Well, yes, I suppose so. But, uh, the, um, you know, I I,

Brian Huberman (00:48:18):

You know, as I, you know, it, it's corny thing to say, but when I was a kid, I experienced, uh, things like the Alamo in one way. And now I'm an old person. Old, really old. And, um, and I experience it differently. Of course, it's different, you know, it, uh, that's what happens. You know, we, we grow the, it's, it's just a, a real a fact. We change in all ways. And, uh, what I hate is to see the rigidity of people, like any political movement that it's going back, Make America great again. You know, that's like death. That so misunderstands great American myth, which is a progressive myth, which is always moving forward. Movement, movement. It's never the same. You know, if you're not prepared to throw your grand piano out the back of your wagon, you are just not into the American, uh, spirit. You're not into it. And these mega fucking hooligans, um, are, are, are a kind of a, are are a dreadful perversion o of the American experience. And they, and they're dumb. They're fuckingdumb. They're so fucking dumb. I feel like the old man in, um, in, uh, treasure of the Sierra Madre. You're so dumb

Chris Newlin (00:49:57):

So what was the most surprising thing you ever found out about the Alamo or its, or its heroes in your research? I helped you, uh, assisted at some little small part in editing a couple of your documentaries.

Brian Huberman (00:50:09):

You certainly have. And one of them was that, uh, the, the De la Pena diary, which, which

Chris Newlin (00:50:14):

Was amazing. Yeah,

Brian Huberman (00:50:15):

That was a big one we did.

Chris Newlin (00:50:17):

So you were into Alamo revisionist history before it was cool.

Brian Huberman (00:50:19):

Well, I didn't think of it. I mean, right. I understand as revision

Brian Huberman (00:51:51):

It, it's the, it it's that image of the rednecks in front of the Alamo with their ar fifteens. They shall not pass. It's the, that, that kind of, we will die before we switch from Tarn, you know? Mm-hmm.

Chris Newlin (00:53:29):

But why do you think he said he, he didn't care for the vibrance of our nation. Just,

Brian Huberman (00:53:34):

He just said it was hard. It was hard being the neighbor of such a kind of a bustling force, fierce, energetic, rich, you know, um, uh, a nation is that, and, uh, you know, the roots of that of course, uh, go back to the beginnings. You know, you can see that in the writings of Mexican, uh, uh, leaders in the early 19th century who understand all too well the mechanics of American expansionism, or American imperialism, if you wanna use the big word.

Chris Newlin (00:54:13):

Um, and they saw the writing on the wall. Oh

Brian Huberman (00:54:15):

Yeah. I mean, they just understood absolutely how, how the frontier works. You just let some of those dollar trappers in first, you know, American kind of rugged individuals with their families and stuff, and they just tough it out in against Indians and whatever. And they drive in their state, you know, they occupy hold, and then it's like a vanguard for the big movement. That's how they go. And, uh, uh, and, you know, the Mexican story was attempting to kind of combat that, that strategy. And, uh, and of course they weren't, uh, they weren't able to do that

Chris Newlin (00:55:08):

And here we are

Brian Huberman (00:55:09):

And, uh, kind of apply sort of a social Darwinism to it. Right? Well, you know, that's one way of looking at it. Well, then we can justify the conquest of everybody, you know, fine. You know, um, uh, but if you want to take a more human view, you know, then, uh, you know, I want to, I want to play with the full deck of cards. And, you know, when we crossed the river with our cameras to go to, to Mexico, then that was, uh, that was expanding the deck. Right. Big time. And, uh, and I kind of really felt, you know, the shifting of the trope as some have called it, instead of the camera being inside the walls of the Alamo, we were now outside the wall. Wow. Looking at it, it was an interesting shift in, in, in, in vantage point.

Chris Newlin (00:56:04):

What I know we're, I've kept you a long time. I just got a couple more things. But, um, are there any other highlights of documentary projects or films you've done over the years that you reflect on that are your favorites? Or,

Brian Huberman (00:56:18):

Um,

Chris Newlin (00:56:21):

Does last night at the Alamo, wear well, with you or,

Brian Huberman (00:56:24):

Well, that was not a documentary, that was a feature, right? Last night. Yeah. That was, uh, working with Eagle Pennell,

Chris Newlin (00:57:21):

Well,

Brian Huberman (00:57:21):

Um, and, and then you had to move the shuffle board table out into the parking lot cuz it was in the way. I, being the documentary filmmaker said, let's keep the shuffle board in there. That'd be great. We can have them playing shuffle board and No, no, that kinda,

Chris Newlin (00:57:38):

The camera has to go right there.

Brian Huberman (00:57:41):

So,

Chris Newlin (00:57:41):

So, so over the years, you, you certainly have, have made these films, various films of various projects and you must have met what, what, what am I wanna say here? Um, uh, oh, hang on. And you've met amazing people. You've, you know, I remember working with you on your Holocaust films that, that the act, the Holocaust Museum, I guess they still show them where you interviewed all the Holocaust survivors in this area. That's right. And, and I remember how it was depressing as can be of anything I've ever sat through in an edit room watching hours of that testimonial and yet poignant and enlightening and all of those things. Um, what, what projects have stuck with you over the years or the, how, how has, how has the career of filmmaking changed you?

Brian Huberman (00:58:33):

No, God. Wow.

Chris Newlin (00:58:35):

Take any part of that. You want

Brian Huberman (00:58:37):

God almighty, um, um,

Chris Newlin (00:58:42):

Or just any, any people project that's really affected you in a certain way.

Brian Huberman (00:58:47):

Being able to, to work on, on documentaries of my own choice usually, and being able to take as much time as I wanted to on them has been my lot. I've been fortunate in that case. Uh, I, I think I have, it's not a way of making films that would suit everybody. Some people need the, the, the applause of audiences regularly. And I've had to do without that because I haven't always, you know, been able to have a, a venue to show some of these films. And some, I have like the Holocaust stuff, of course, you know, that was made for the museum. So there, there was an outlet for that. I mean, the, the, it's, it's a great thing in, in documentary generally that to, to, to have the opportunity to go out into the world and kind of find out about stuff to kind of broaden one's experience.

Brian Huberman (00:59:51):

I mean, that seems to me as the, is the bottom line. And I say that because, uh, and I look at, you know, the way the technology has gone, you know, so much filmmaking is done in, in computers, and it seems to me in this, which is way above me, Mike pay grade. Um, but, um, uh, and that's fine for them, I guess, but it wouldn't work for me. I mean, the, the joy I get is going out. And if I didn't have the camera, well, I'd have a notepad or something, or a rock, and I'd scrape my designs on a cave and, uh, and, and leave them that way. I think the, the, the, the important experience is having the experience. So in the Holocaust film of, of course, it was shocking, absolutely shocking. Um, and when I was offered the, the deal, I thought, well, this is it.

Brian Huberman (01:00:48):

This is, uh, the, the greatest oral history project you could possibly be part of in this moment in time. And so I was not going to avoid it. Um, and I thought it was a challenge for filming it because, uh, in, you know, in the invariably during these sessions, we would end up in some pretty kind of dark places if, if these people, some subject skidded over them, understandably. And, and, and others went right into them. And so, you know, down into them you went too. And the qu it's a big challenge for the camera operator. Uh, let's be specific about which part of the filming process. It's a person with their hands on the fucking lens at that moment, uh, when somebody is dissolving in front of you because they're now back at the train station at Auschwitz, kind of being separated from their family while dogs are biting at their ankles and, and, uh, so forth.

Brian Huberman (01:02:01):

Um, and for what do you do? And my impulse, I mean, in my guts it was to look away. I thought, this is just awful. You know? And because, uh, because the eyes of your subject are in what they're revealing are connecting you to this horror. There's no other way to put it. And my instinct was to turn away. But my, my professional instinct, yeah, it, it, it told me not to look away. And, uh, I thought actually of a film by Rossellini, I have to tell you this. Um, there's a film by his called Open City. It's Rome, Open City, it's famous, his most famous neorealist film. And there's a scene in that film where a priest is being interviewed, interrogated in a room, and in the next room a partisan, a friend of his is being tortured.

Brian Huberman (01:03:07):

And, uh, they're trying to get the priest to tell 'em where the Nazis are, trying to find out from the priest where the partisan are hiding or something. And uh, at one point they opened the doors between the rooms so that the priest can now see the man being tortured as a way of forcing him to speak. And the priest holds his eye on, on this tortured individual, but will not speak. But nor will he turn away his gaze. And so I would go in on these people when they began to do that, instead of pulling away to a discrete widest shot, you know, takes the pressure off them. I would actually put the pressure on and

Brian Huberman (01:04:16):

Because when I zoomed in, it wasn't because I was zooming in on their pain. It was, I was showing their the wrinkles old faces. That's right.

Chris Newlin (01:05:30):

Get the shot? Did we get the shot? Well,

Brian Huberman (01:05:33):

That's

Brian Huberman (01:05:34):

Anyway. Um, and then working with James Blue on, uh, the, the fourth Ward film, the Who Killed the Fourth Ward, which was a very early project for me here was, uh, a huge ob you know, Blue was, uh, you know, an ex extraordinary character. And, uh, at that time I was kind of very young. I was still in my twenties, so I thought Shit! like, you know,

Chris Newlin (01:06:20):

This was just in regards to the subject matter or him as a person? What do you mean?

Brian Huberman (01:06:23):

No, no, just as the way he filmed. Oh. Oh, I see. Um, he was, uh, the fourth Ward was a tricky subject. I guess. It involved big subjects, city hall, leaders in City hall, big business leaders. And uh, and then, uh, the, the people from the community of the fourth Ward

Chris Newlin (01:06:45):

And, and for our listeners, the Fourth Ward is a, an old neighborhood that was right at downtown. That,

Brian Huberman (01:06:51):

That's right. It's now being gentrified. Yeah. Rapidly. It was formally Freedman's Town. Friedman's Town. It was the first black community freed black community in the city, I think. Right. And it did by, in the 1970s, it was when we were filming, it was a very decayed, dilapidated, um,

Chris Newlin (01:07:12):

Row after street after street of shotgun houses

Brian Huberman (01:07:15):

And, and churches. Very bad condition. And, uh, it was so, it was a complex film kind of studying, you know, why as an area like this sort of allowed to decay. You know, do the kind of regular people, the poor people do, you know, do, do they have any say over how a city grows? Well, who does? Well then there's big business, you know, who are the people that actually do the stuff? And then the city who seemed to mediate between the people and the, anyway, it was, uh, as I said, an incredibly complicated film because the city doesn't know what it's doing. It just does it, it seems to me. And a lot of it is hidden. I don't know whether they mean to hide it, you know, it's never clear that you ne you, you hunt for a smoking gun on stuff, and they're never one there.

Brian Huberman (01:08:15):

It's, uh, it, it, it's an incredibly frustrating, uh, experience. And at one part of it, it came to a head. There's a church that was formally part of the fourth ward called, um, Antioch Baptist Church. It's still there. It's surrounded by parking lots and skyscrapers. Totally cut off from it from anything, but it's survived. Well, in 1976 or seven, there was a vote there, there was a, a minister at that time whose name I forget. We filmed him and he, uh, um, he appeared to be working with, with developers. And, uh, the plan was that, uh, they would, it seems like that he was working with developers that Antioch Baptist Church, that land would be sold to developers to build their skyscrapers. And, uh, the money they got from that would allow the people to build a new church somewhere else. And there was gonna be a vote over it.

Brian Huberman (01:09:22):

And we were deep in on this thing. And we, like I said, we'd been filming, uh, the developers, we'd filmed the kind of minister. We were filming the people. We were everywhere. Film, film, film. And uh, and, uh, the night came of the vote and the people voted to save the church. This is the people of the church voted to save. That's right. They voted to, to keep it where it was. And so thwarted the plan to the minister. And, uh, it was a great moment. It was a big, it was a, it was a big payoff after all this buildup and and so forth. And I wanted the final shot, cuz we were there that night at the church. We filmed the people coming out, singing and all that stuff. Mm-hmm.

Brian Huberman (01:10:22):

If you racked focus the beaten man, the minister is walking the way alone to his car. It's a great moment. And I wanted it, you know, but in those days, we're shooting super eight. Oh my God. And, um, I have to have a sun gun with me. Oh no. And that means he has to come, Blue has to come with me, otherwise I can't get the shot, you know? And, um, he wouldn't do it. Ah, he wouldn't do that. He wouldn't get that final shot. And uh, uh, I thought that was unforgivable. You know, we don't have to use it in the editing room. Maybe we have to shoot it. You know, that's just the, uh, as far as I'm concerned, that's, that's just, uh, unquestioned. Right. And, um, he did this kind of cowardly thing. I mean, I, I felt, and I threw the fucking camera at him. I mean, I'm just, it was, uh,

Chris Newlin (01:11:29):

Uh,

Brian Huberman (01:11:31):

So yeah, that's, that was at the Great James Blue. Yeah.

Chris Newlin (01:11:37):

Mm. So tell me just real briefly, uh, about, um, have you enjoyed teaching, uh, is, I mean that's part of your role here.

Brian Huberman (01:11:56):

Profess

Chris Newlin (01:11:56):

I these films and you're, you're a filmmaker. That's what you do. Right? Right. That's so you make films instead,

Brian Huberman (01:12:02):

God damn. Right.

Chris Newlin (01:12:04):

And so

Brian Huberman (01:12:04):

A lot harder than writing a book. But,

Chris Newlin (01:12:06):

But, but in between, you do have to teach a few classes. Have you enjoyed that? And how's that changed over The years?

Brian Huberman (01:12:11):

Yeah, no, I did. I have, because the, the classes that I teach are, are, are about what I do. So it's, you know, my classes are in, I I would just say basic introductory, uh, filmmaking, um, very introductory now cuz um, I've not really kept up with the technological, um, advances that have occurred. But, uh, so I'm not, you know, I don't, I don't, I don't teach a trade school kind of mm-hmm.

Chris Newlin (01:13:32):

You, what you would define as like technique and, uh, execution of getting your picture as opposed to the art of a, of a vision of a grand vision. Yeah. Something you have a, do you have a definition?

Brian Huberman (01:13:46):

Well, obviously you do have to have some, if you want to use the word technique or, or technical control, you obviously have to have some of that. But it, it's, um, it's just where do you put the balance, you know? And, um, uh, you know, uh, you know, I'm quite happy to put the camera into auto, you know, if necessary. Right.

Brian Huberman (01:15:19):

Uh, the software for, for editing, digital editing, you know, the, the way in which the, the programs are laid out, it's like a film ta, it's no different in fact than working on film, except it's fuck of a lot faster. You know, that's, that's the, the glory in it. Um, so, uh, what I provide is sort of an archeological experience. It's, uh, like going back into the past and it, and it's great because, you know, digital is a clean world and film is dirty and wet and it stinks and all that stuff. And in, in my class, you know, not only do they, um, you know, shoot and so forth, but they also develop the film themselves.

Chris Newlin (01:16:11):

Oh wow.

Brian Huberman (01:16:11):

You know, in the bucket, you know, so it looks kind of, uh, weird and in, you know, because it's unevenly developed, but it has a kind of a raw quality to it that's sort of.

Chris Newlin (01:16:22):

very vintage

Brian Huberman (01:16:23):

very vintage.

Brian Huberman (01:16:24):

That's it. And, um, and, and, and I enjoy that. So, and I found actually maybe it's no surprise as I get older, I'm actually going back

Chris Newlin (01:16:36):

further and further,

Brian Huberman (01:16:37):

further back. Well, yeah, I've found it's, uh, it's not a retreat. It sort of just seems relevant to me. I don't know.

Chris Newlin (01:16:45):

And do the kids enjoy all this?

Brian Huberman (01:16:46):

Yeah, they do. I wouldn't have continued, but I thought they would never do it. I was kind of bullied into it by a coworker, and I thought initially they're never gonna put up with it. It's much more work than any of the other video classes. And, uh, and, and the, the most of the time they've enjoyed it. Yeah. They get a bang out of it and they, they sense that they're in a special cadre of human beings.

Chris Newlin (01:17:15):

How have kids creativity changed over your time here? Are they better? Are they worse? They take more things for granted? Is it, has computers made it too easy? Have computers made it to me?

Brian Huberman (01:17:25):

Oh, I don't know. I mean,

Chris Newlin (01:17:27):

Ugh. You still enjoy them though. You enjoy the kids.

Brian Huberman (01:17:30):

Um,

Chris Newlin (01:17:30):

Is it harder?

Brian Huberman (01:17:34):

Yes. I mean, I think, uh, you can get, it's when you have a good bunch of students who, who are sort of willing to get into it, pick a subject that they're really interested in, that's the hardest thing. These fuckers will, you know, you know, they not appear to be interested in anything. And so if you are not interested in the subject, and then the footage isn't gonna be interesting to us either, because you are not trying to find out anything. You're not really committed. There's always some students who fail because of that. And, um, but then there are others that kind of get the idea that, uh, they're on an adventure.

Chris Newlin (01:18:27):

That's great. So tell me, we'll wrap it up here, is, uh, I, I didn't know how to phrase this. You've been fascinated with Texana and, uh, you married a woman or your partner is, uh, part are all Native American blood,

Brian Huberman (01:18:45):

Right? Yeah. She, Cynthia, she's,

Chris Newlin (01:18:48):

Was that happenstance or did you

Brian Huberman (01:18:50):

Oh no, cuz I went out looking for an Indian girl.

Chris Newlin (01:18:57):

How much truth is that, is there in that?

Brian Huberman (01:19:00):

No, I went hiking alone in New Mexico many years ago. And, uh, I came down out to the mountains and went to this store to buy a t-shirt or something, and she was working there and there was a sound of trumpets. No, I, you know, it's a coincidence. But, um, it, it, it's been a, it, it, it's worked well. I mean, why, why does any relationship fail or survive? And it hasn't hurt our relationship that in some ways we share, kind of connect like my Geronimo project, which I, which

Chris Newlin (01:19:48):

Is I was gonna get into that Was my final,

Brian Huberman (01:19:49):

which is current Epic, um, uh, kind of partly I think grew out of, um, her interest in, you know, her people as she would put it. And um, and uh, my kind of interest in westerns and the, you know, the standard western myth. So there we are our different points than, then finding our way together. And, and she's actually one of the subjects in the film.

Chris Newlin (01:20:23):

And briefly the Geronimo project is...

Brian Huberman (01:20:25):

Is, well, it's, uh, it, it's, it, it's it, it's a film that made up of, uh, many threads, but it's the main thread is the, uh, surrender of Geronimo, his final surrender, which took place in a place called Skeleton Canyon in south, uh, east, uh, Arizona in 1886. And, uh, that, uh, the, the film started off by wanting to go to that place. And I couldn't get to Skeleton Canyon because there were so many drug lords and, and, and.

Chris Newlin (01:21:08):

oh my god.

Brian Huberman (01:21:09):

And, uh, illegal alien crap and all of that stuff that the residents, like the two or three landowners in that vast empty land down there bought this road to Skeleton Canyon and locked it, made a private road out of it. Right. So I couldn't get there,

Chris Newlin (01:21:49):

to let her in

Brian Huberman (01:21:49):

to give us the combination to the lock. And so we eventually at some about the third episode, we get into Skeleton Canyon and uh, and, and what a place it is. It is the first thing that greets us is a rattlesnake. You know, it was not.

Chris Newlin (01:22:08):

sets the scene,

Brian Huberman (01:22:09):

it's all too good to be true. Right. And, uh, and um,

Brian Huberman (01:22:16):

And and the, the, the, the, the, the film basically follows on and off a, a trail of going to places related to Geronimo's story. I mean, we eventually go to his, uh, death place in Oklahoma. He's got a, a grave there at Fort Sill. Um, we went to, uh, into Mexico at one point to a place called Cañon de los Embudos, uh, which is an epic place in the Geronimo story. It's actually an epic place in American frontier history cuz it's there that Geronimo in the meeting with General Crook of the United States Army were photographed by the famous frontier photographer CS Fly of Tombstone. And, uh, he followed Crook into this meeting and, uh, the Indians actually agreed to be pho tographed and Fly took, I think 18, I think it's 18 photographs that are the only photographs ever taken of American Indians still hostile and in the field.

Brian Huberman (01:23:29):

Ah, all the other photos are after. Correct. They've been given a broken gun to hold, you know, and that, but these are the real thing. And uh, they're kind of, it, it's a totally iconic place, but getting to it because of all the Goddamned drug lords and stuff was just a nightmare. And, uh, again, that's part of the part of, uh, part of the story. Plus I'm not in, in good health, and so I'm become struggling with that along the way. And other characters in the film are an Apache medicine woman called Karen Geronimo, who was kind of very fun and, um, provides Apache texture in the scenes that we have with her. And, um,

Chris Newlin (01:24:23):

We, we can expect delivery of this film when.

Brian Huberman (01:24:25):

Well, we're, you know, we are working on the final episode. I'm, I'm just wondering how I'm gonna be able to afford to have you, uh,

Chris Newlin (01:24:37):

When you say work on, when you're on the final episode, you've, you've rough cut them all or you're just finishing shooting?

Brian Huberman (01:24:46):

No, no, we've cut the first six.

Chris Newlin (01:24:48):

Oh, okay.

Brian Huberman (01:24:49):

The first six.

Chris Newlin (01:24:49):

So you're moving along.

Brian Huberman (01:24:50):

Oh yeah. No, we're, we're, it's, uh, wow. It's, uh, it, it it is an epic

Chris Newlin (01:25:35):

Well,

Brian Huberman (01:25:35):

And, and you know, and it, this is a film. I, you know, what kind of films do I make, ones that I wanna watch, you know, it's not a big surprise, is it? And, um, and I enjoy watching my film, you know, I will say,

New Speaker (01:25:35):

Chris Newlin (01:25:49):

what more could You want

Brian Huberman (01:25:50):

Yeah. I, you know, I I I have them on Vimeo so that I can bring 'em up on my big screen at home. And.

New Speaker (01:25:58):

goddamn it, I watched them from time to time. Well,

Chris Newlin (01:26:00):

And the, the streaming world changed things as terms of mini-series and multi-part pieces. Well,

Brian Huberman (01:26:05):

Of course, that it's, it's totally correct in terms of format of that. Yeah. Except that I don't have movie stars and stuff. How will people survive? You know, without, uh, the confidence of somebody from Mount Vernon being kind of transported into the, into the experience. I'm gonna have to go.

Chris Newlin (01:26:26):

Okay. I was just gonna say, is there anything else we didn't talk about that you really wanted to say or the life and times of Brian Huberman

Brian Huberman (01:26:31):

dog? My dog, my dog who is patient, supportive, and all my trials.

Chris Newlin (01:26:42):

All right. Thanks Brian.

Brian Huberman (01:26:44):

Thank you.