The Truth About Black Eyed Peas and New Year's Day

Given the humble origins of the food itself — generally seen more as animal feed than fit for the better tables in the South — it seems very likely that the tradition began in the slave quarters like so many others.

No, Rip Torn's dad did not invent the tradition.

Black-eyed peas for New Year’s good luck? Ancient Southern tradition, or romantic invention of the creative mind of a postwar Texas ad man?

Until relatively recently, I’d little reason to question the former proposition, but in 2007 professional Texan Charley Eckhardt’s 2007 story "The Great Blackeyed Pea Hoax" brought in a wave of what are now au courant debunkings of the tradition's allegedly venerable origin.

Wrote Eckhardt:

Did you eat blackeyed peas for good luck on New Year's Day? Did you do so because it's a 'great ante-bellum Southern tradition?' If so, congratulations. You have been scammed by one of the most likeable con-artists in Texas history.

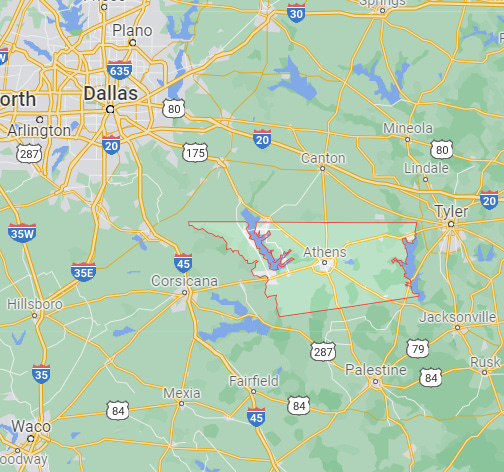

According to Eckhardt, ad man Elmore Torn, the father of actor Rip Torn, was tasked with singing the praises of Henderson County, Texas, which in 1947, had little more to offer the world than farming, oil, and 200 gigametric fucktons of black-eyed peas. And a cannery for those peas. And so Torn made the most with what he had.

Eckhardt said that the canned peas of 1947 were quite unlike those of today, in that they were damn near inedible:

When you opened a can what you saw was something that looked like lumpy, grayish-brown library paste with dark brown spots scattered in it. What you tasted was, in essence, salty tin. The canning process picked up the taste of the metal the cans were lined with. In other words, that stuff was downright awful and it's a miracle anyone ate it at all.

And so Torn weaved a romantic tale of their origins deep in the Spanish moss-draped past, that they were, in Eckhardt's words "a long-standing Southern culinary delight that graced the tables of high and low society all across the ante-bellum South, particularly on New Year's Day, when no proper Southern table would be without them."

If you were wondering why you'd never heard of that tradition, you had the damn Yankees to blame for that. Torn claimed that the occupying Federals put the kibosh on blackeyed pea consumption during Reconstruction, and were so effective in doing so, the tradition was teetering on the brink of extinction. The Yankees did so because they had learned that Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee had enjoyed this traditional January 1 repast, and stamping it out was a vindictive form of petty payback.

And so, Torn concluded, in the spirit of letting bygones be bygones, as the Centennials of Fort Sumter, Gettysburg, and Appomattox approached, why not revive this relic of the antebellum South? And what easier way to do it than with a can of Henderson County's finest blackeyed peas?

Torn printed all this up in the form of a pamphlet -- Eckhardt explicitly called it a "scam" and refers to it as a "hoax" in the headline of his story -- and dispatched it along with tiny cans of peas to food editors at big city papers across the South right after Thanksgiving.

Up until then, Eckhardt points out, unlike Christmas, Thanksgiving, Easter, and the Fourth of July, New Years Day lacked a traditional meal, and Torn was determined to fill that void.

Eckhardt continues:

Exactly how many food editors bit Elmore's hook we don't know, but he continued mailing copies of his scam and the 2-ounce cans of blackeyed peas to food editors across the south for several more years. Each year more and more food editors got on the bandwagon. Elmore started the 'tradition,' not of eating blackeyed peas per se, but the specific 'tradition' of eating blackeyed peas for good luck on New Year's Day-a 'tradition' which had never existed before 1947.

Okay, there is little I have enjoyed more in my career than a good old-fashioned debunking. Reading them, and even more writing them. There are few more thrilling prospects than standing tall and all but alone in a vast tide of buncombe while armed with nothing more than the incontrovertible truth.

On first reading it years ago, my feelings on the Torn story and Eckhardt's debunking were complicated and ambivalent. At first I swallowed the story that the custom was so old its origins were lost in time, and in more recent years, I have just as eagerly propagated Eckhardt's revisionism as fact, when, I am now afraid, that is patently false.

I think what we have here with Eckhardt’s hoax claim is a failed debunking, albeit one created with the best of intentions.

It's readily apparent that Eckhardt did not regard Torn as malicious or that his alleged "hoax" or "scam" was some great calumny. On the contrary, Eckhardt's goal was to exalt Elmore Torn's slickness as a PR man and to highlight how this Henderson County country boy pulled one over, first on the city slickers in the big cities of Texas and the South, and then the whole country.

The thing is, he really didn't.

Elmore Torn may well have done an amazing job of popularizing the tradition of eating blackeyed peas on New Year's Day, but he most certainly did not invent it out of whole cloth, as Eckhardt has characterized it. (The Associated Press had this to say in its 1971 obit:“Mr. Torn was known for having started the custom of eating black-eyed peas on New Year’s Day.” Well, note the weasel words: "Mr Torn was known for having started" is not quite the same as "Mr. Torn started...")

A quick glance through the database of Newspapers.com turns up several examples predating Torn's legume jihad by years, decades even:

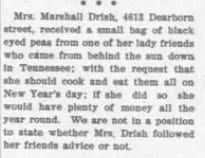

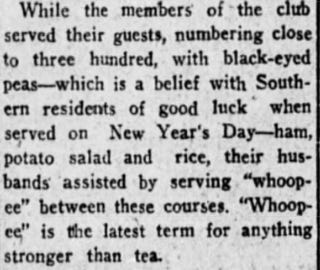

To wit, an item from a January 1904 issue of a Salt Lake City paper reveling in the name The Broad Ax:

So, here we have a Southern woman touting blackeyed peas as bringers of good luck if eaten on New Year's Day four decades before Torn's spiel. The odds against Torn simply inventing such a tradition that coincided exactly with this account are infinitesimally small, but hey, million typewriters, monkeys, Shakespeare, and whatnot. Maybe it was just a coincidence.

But this is not the only account.

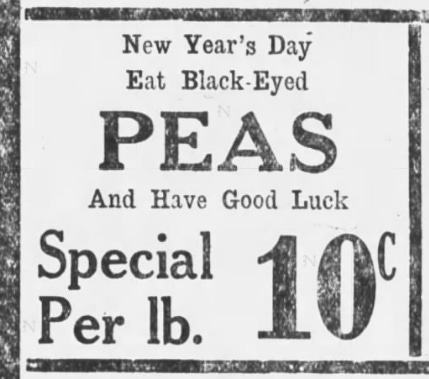

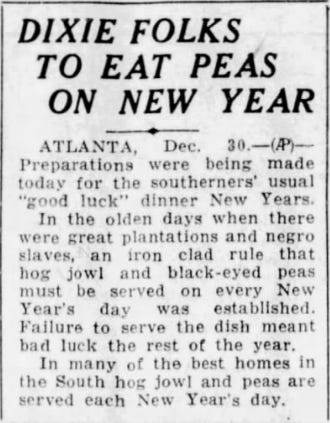

Here's an H.G. Hill's Grocery ad from the Chattanooga News on the first day of 1926:

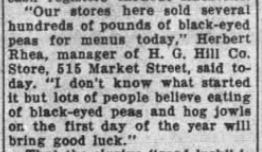

Same grocer, same paper, almost three years later:

As the Twenties roared on, the peas made their Gotham City debut, courtesy of young African American women, holding up the culinary end of the Harlem Renaissance. Clippings from the New York Age, January 5, 1929:

(I think they might be insinuating that there was alcohol on the premises, Prohibition be damned.)

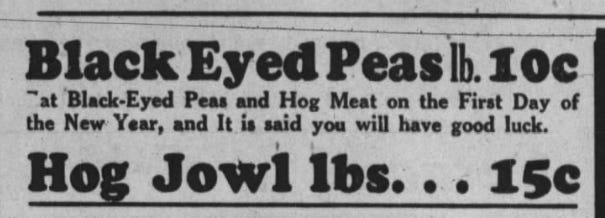

In 1930, the Birmingham outlet of the newfangled Piggly Wiggly chain of supermarkets was peddling them, along with hog jowls, for their lucky properties and as "a time-honored tradition of the 'Old South'."

On New Year's Eve 1930, the Charlotte Observer offers up the earliest origin story I was able to turn up:

Which is sort of frustrating because it offers no explanation as to why this became an ironclad rule, apparently across wide swaths of the Dixie of yore.

It's also intriguing to me that these newspapers felt duty-bound to spell out to their own readers about this ancient tradition. Wouldn't the people of Charlotte and Birmingham know that already? Wouldn't that be like telling a Boston Irishman about the time-honored tradition of getting sozzled on St. Patrick's Day?

Maybe, maybe not. Neither Charlotte nor Birmingham are typical Southern cities. Both are in the upland South, and Birmingham was a steel town with lots of migrants from all over the country and immigrants from abroad. Piedmont North Carolina was not plantation country, and so lacked the Big House traditions of the Tidewater to the east.

That could explain why the readers of those papers needed to be told about these traditions, or maybe not. Maybe Torn had a fore-runner in the invented tradition game. What can be said with certainty is that the tradition's origins predate his wildly successful campaign.

The tradition seems to have spread along with the rise of Southern grocery chains like HG Hill and Piggly Wiggly.

On New Year's Day 1932, a writer for the Knoxville News-Sentinel was as puzzled as I am right now:

In that darkest depth of the Depression, the writer noted that "elusive 'good luck' was being sought more ardently than ever."

And as for Herbert Rhea's bewilderment over what started it, I am beginning to believe that it might have been the owner of his company, the Nashville grocery / real estate mogul H.G. Hill.

Note that the first account we have of black eyed peas and good luck dates back to 1904 and is sourced to Salt Lake City woman who came there from Tennessee. HG Hill's grocery empire started up in Nashville in 1895 and by 1906 it had cornered the Nashville market with 12 locations. By 1926, it had spread across Tennessee and the Mid-South, first to Knoxville, Chattanooga, Birmingham, and Huntsville, and then to Montgomery and even as far west as New Orleans: 500 stores in all, at its peak, at least some of them running ads touting the lucky properties of blackeyed peas and hog jowl on New Year's Day. (Hill's empire contracted greatly, but was still very much a player in the Nashville of my youth.)

So that's my theory -- Rip Torn's dad picked up where H.G. Hill left off and perhaps greatly embellished the story with his tales of Yankee suppression and even that they were commonly consumed by all, high and low, before the war. Other scholars insist that they were something like the vegetable equivalent of offal, fit only for animals and the poorest of the poor.

As to where Mr. Hill got the story, further research is required. Some have said that the tradition may have started in Africa and come to America on slave ships, and some credence is given to that theory by the fact that this tradition also exists in the former British and Dutch South American slave colonies of Guyana and Suriname.

And it’s also found in the African American folklore collected by Thomas Talley, a chemistry professor at Nashville’s Fisk University who turned to collecting folklore as he edged toward retirement.

In his 1922 collection Negro Folk Rhymes (Wise and Otherwise), the first collection of secular Black American folk verse, we find the following poem:

One time I went a’huntin’

I heard that possum sneeze,

I hollered back to Susan Ann,

Put on a pot of peas.

Dat good ol’ ‘lasses candy,

What makes de eyeballs shine,

Wid possums, peas, and taters,

Is my dish all de time.

*Dem black eyed peas is lucky,

When e’t on New Year’s Day,

You always has sweet taters,

And possum come your way.

*This last stanza embodies one of the old superstitions. (Talley)

So according to Talley, the tradition was already old in the early 1920s, old enough to have been preserved in verse. Given the humble origins of the food itself — generally seen more as animal feed than fit for the better tables in the South — it seems very likely that the tradition began in the slave quarters like so many others.

I am not a fan of the concept of cultural appropriation, but I really hate it when credit is not given where it’s due. Clearly, to me at least, this is an African American tradition later adopted by canny American marketers with Rip Torn’s dad just among the more successful.