Transhumanism and All My Mortal Friends

Stolyarov claims that the first part of accomplishing immortality is to believe it is possible and dying is not required. Teach that to the young and the world will change. Death, he chants like a mantra, is wrong.

“If in my youth I had realized that the sustaining splendor of beauty with which I was in love would one day flood back into my heart, there to ignite a flame that would torture me without end, how gladly would I have put out the light in my eyes.” - Michelangelo

We were afraid to think much about spring during the month of March up in Michigan. Too many days the weather gave us a false hope of warmth when a Chinook wind melted the ice and showed frozen green sprouts from the previous summer, and then a blizzard blew a cold cover over our dreams of sun. In college, though, if we found money, a trip to Florida made us think that by going away for a week we might come back to a vigorous spring and a state in bloom. Michigan weather, though, was always cruel to youthful optimism.

I was working in the dormitory cafeteria and had met a farm girl who was distracting me from motorcycles and books and running. My buddy Murph, who lived on the same floor in our old brownstone dorm, suggested I try to save a few hundred dollars and ask her if she wanted to travel to Florida for spring break. He was confident his girlfriend was going to make the trip. I thought Florida was for people with real resources, and, regardless, I had no concept of myself on a beach. Murph, however, was relentlessly happy, and convinced me, not just to make the trip, but to also take more chances.

He had a late model car his parents had provided for him to get around campus and for trips home on weekends. In the house where he grew up down in South Bend, there was a dry sauna in the basement. I saw it on a weekend when he invited a group of us for a hockey game between Michigan State and Notre Dame. The sauna was bigger than the bedrooms in our little house south of Flint. There was also a pool table upstairs, which we all used during a party after the hockey games. Murph’s parents had gone to Florida and had allowed him to invite guests for the tournament.

Our trip began during spring break in late March, and we drove down Interstate 75 and the old Dixie Highway, the road that had led homesick southern boys north from the farms to the car factories and the steel plants for jobs after World War II. Cold rain splattered against the windshield as we sped southward and fantasized about the beach in Ft. Lauderdale. When the Atlantic came into view along A1A after 24 hours of traveling, I was almost breathless at my first sight of the ocean. The sun was also suddenly warm, and the farm girl smiled beside me as Murph sipped coffee and his friend Patty chattered in the front seat.

We were young and our lives were endless, and the road was smooth and flat.

* * *

In 2013, there was a modest demonstration on the campus of Google in California that few people noticed. A small group of individuals stood outside the Googleplex and held signs that said, "Google, please solve death," and "Immortality now." The small gathering marked the tech giant’s announcement of a new initiative called Calico, which was designed to focus on health span, living well for a longer time, but also senescence and the ravages of years and the effects of aging on the human body. Perhaps, an end to death?

Calico launched with significant credibility, and not just because of the imprimatur of Google, and, later, Alphabet. Arthur Levinson, the former CEO of pharmacological research giant Genetech, took his reputation and record of achievement to the new endeavor, which also hopes to uncover and correct the biological pathways of aging and diseases. Calico immediately developed a partnership with AbbVie, another global biopharma corporation, and both companies have recently added $500 million each to a few billion already spent for research efforts that have produced almost two dozen early-stage projects focusing on neurodegeneration and immuno-oncology.

There are also hopes that the planet's most powerful technology company will concentrate scientific efforts on transhumanism, the idea that we can defy our own flesh and mortal definitions of human life. Discussions have been ongoing for several years about uploading consciousness and memory to computer networks to enable the human experience to continue even if only in an incorporeal form. Science is presently giving us robotics that move artificial limbs with only thought and there is research to stop the cellular decay that leads to senescence and the failure of organs and biological functionality. Google co-founder, Larry Page, hired Ray Kurzweil, a scientist who has written widely about living well and forever, and believes in the “singularity,” a moment when artificial intelligence explodes far beyond human capacities.

British researcher Aubrey de Grey, meanwhile, is certain that age is simply a disease that can be cured. He has identified seven ways human bodies fall into decay and believes they can all be fixed with science and medicine. He has developed what he calls viable Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence (SENS), which he is convinced can end aging and our acceptance of death after a traditional life span. De Grey is working to prove that the metabolic and cellular processes that cause aging can be reversed, and humanity can eventually approach mortality. The science to save us from our biological demise, de Grey argues, already exists, and the only challenges are money and continuing research. In an interview with German television, he insisted that the first human to live 1000 years is alive today and may even be as much as 60 years of age.

The sun turned us pink that week on the beach in Ft. Lauderdale, but we told ourselves we would be brown, and Michigan would be warm by the time we got back north. Nothing could hurt us, and we swam and ran and ate and drank and danced with improbable energy. There was not a moment when Murph was not smiling the entire week and he believed more than I that everything was green and warm up above the Mason-Dixon.

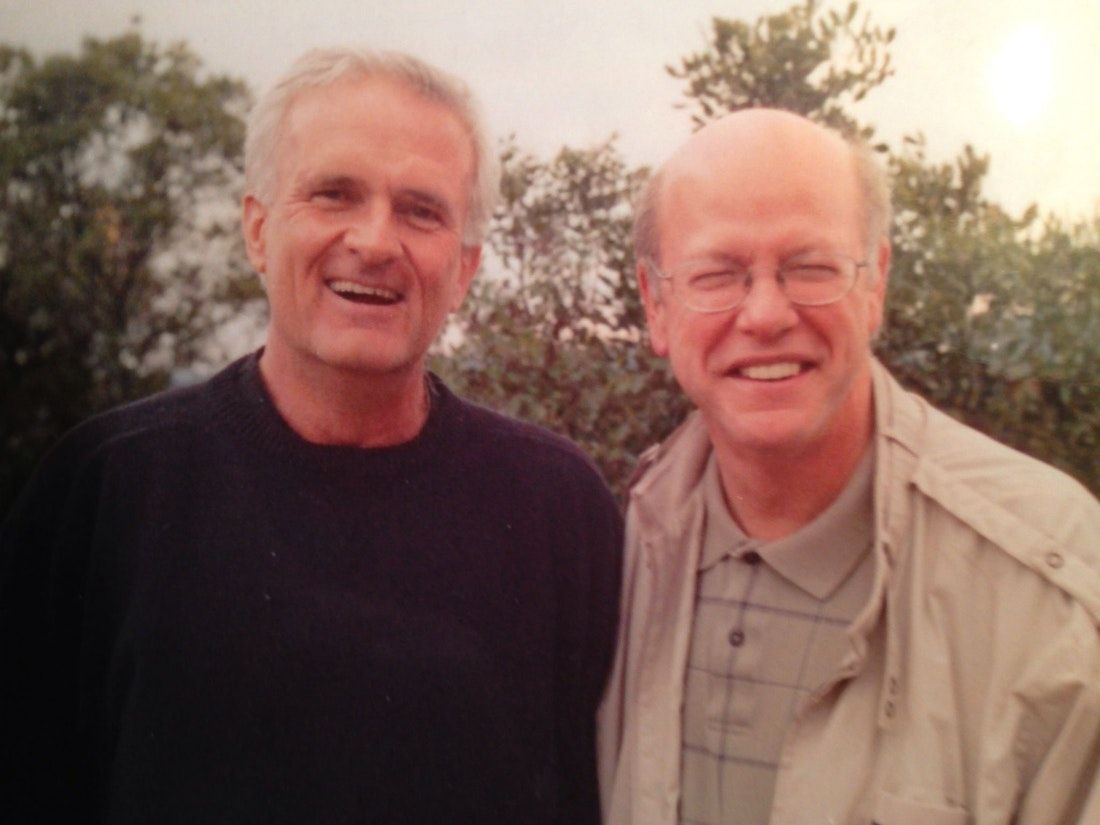

Murph eventually took off on a career that made him an executive in major corporations and when the farm girl and I were living in a crumbling adobe on the border he already had airline privileges and flew down to sleep on our porch and listen to the shuffle of palm fronds in the wind. Murph and I hung out together for a while in Denver, too, and over the decades our lives intersected often enough that we were able to keep alive a friendship that had survived beyond all others from my university days. Everything, to him, was funny, and for me, mostly serious and demanding of intellectual rigor. Our perspectives mutually leavened our lives and sustained our friendship.

As Murph's career ended, he made plans to move to Austin with his wife. A diagnosis of Parkinson's set him back, but he was optimistic about his condition's slow progress and was getting the most advanced treatment possible while he was living near Houston. I had not seen him for a few years until we met him in a restaurant during a road trip to New Orleans and he walked past a window so slowly and stiffly I thought it was a little old widower come for the lunch special and to be around people.

Instead, what I saw was Murph was making his slow exit.

* * *

Gennady Stolyarov II and his wife Wendy Stolyarov do not believe in death. They, too, think science and technology can solve it and, until it does, we need to begin thinking that our end is not a foregone conclusion. They are preaching this gospel of eternity to children in a book they have written called, "Death is Wrong." First, they think, the cultural perception of mortality must be changed, and the best method to achieve that goal is to begin with teaching children. Ages eight and up are asked to consider the notion that they can be immortal. The Stolyarovs used an online fundraiser to publish 5000 copies of their book and began distributing them to families. Stolyarov, interviewed by Wired magazine, acknowledged that he fears death and that has prompted his defiance of its cultural acceptance.

"I don't see any shame in saying that I am afraid," he said. "For me as a person who relies on reason and understanding and anticipation of the future, this is the only condition that's truly unknowable. If you cease existing, what's that like?”

It's not like anything, probably.

There is now, however, no reason to be afraid. Nanobots and drug therapies and various other scientific advances promise a possible reverse to the damage caused to human bodies over the course of time. Cells will be revivified instead of decaying. Why not believe this is possible, Stolyarov asks, because the first part of accomplishing immortality is to believe it is possible and dying is not required. Teach that to the young and the world will change. Death, he chants like a mantra, is wrong.

* * *

Murph did not hang out much after he got to Austin. Instead, he focused on his condition. As his dementia and lack of neuro muscular control increased, he sought alternative therapies like deep brain stimulation but learned he was too far advanced to be considered for the treatment. Murph kept asking me to take him around to assisted living centers because he said his marriage of twenty-five years was in trouble. I drove and talked to him and listened as he asked me the same questions several times over the course of a few hours. When we passed a facility that we had visited a few hours earlier, he liked what he saw and wanted to go inside for a tour and had no memory of having previously spent a half hour asking the manager questions.

We went to get Mexican food one bright Hill Country afternoon and as he was getting out of my car he began to bounce and lose balance and started running to regain stability. I caught him before he had reached the creek. Murph ate slowly like my father near the end of his life, and he could not speak loudly enough to be heard in the noisy restaurant. We were late for an appointment to have a chiropractor "adjust" his back and Murph left most of his food on the plate. I opened the door for him and held it for a group of women walking up behind us.

When I turned around Murph had begun bouncing and teetering forward and ran to get his feet under him and he fell hard on his face across the concrete. There was no time for me to reach him before he had busted his lip open and scraped his cheek. The women helped me get him to his feet and Murph cracked one of his disarming jokes, but he wiped the blood from his mouth eagerly when one of the women handed him a tissue from her purse.

"Still going to extremes to meet girls," he said. "You can see it works."

I laughed and got him into the car and as we pulled out of the parking lot, I saw the tears on his face.

Murph was too smart for his affliction. He knew what was coming. There were more falls and less memory. The MSU memorabilia he had collected and that lined his walls would lose meaning. He would forget the autumn afternoons waking beneath the orange and yellow trees filled with anticipation and talking with friends on the way to the football stadium. Who he was, what he knew, what he could do, was going away. And he did not want anything to do with what he was about to become.

A Saturday night in February, Murph took several bottles of muscle relaxers and maybe some ecstasy and went to sleep. When he did not awake the next morning, his wife had him transported to an emergency room. Tubes were inserted; he was stabilized and taken to intensive care.

Over the course of the next few weeks, he opened his eyes a couple of times. Murph heard my voice and awoke and looked at me, unable to speak because he was intubated, and tears trailed down his cheeks. I asked him if he wanted to stay around or go and that if he chose to remain alive to blink his eyes. I did not know if he lacked the power to blink but there was no response. He went back into his coma. His wife wanted to sign a DNR, do not resuscitate order, in the event Murph went into cardiac or respiratory arrest but the hospital ran background checks and discovered that she had filed preliminary divorce papers. Hospital ethics no longer allowed her authority over her husband and a committee authorized me to disconnect my college roommate from life support. I only wondered about the possibility of Murph regaining enough cognitive perception to tell us what he wanted but his doctors assured his wife and me there was very little possibility of such a development, and I was certain what his desire was based on the behavior that had led him to that ICU, and our long friendship.

I thought about the yellow house we lived in on Cedar Street up in Michigan with three college buddies and how we sat on the porch and drank beer and dreamed up our futures and I envied Murph's musical talent and the way everyone in a room stopped when he started to play the piano. I do not think he liked the attention, but I know he loved the music. His life was full, and he would have been a funny old man and a good friend to laugh with at our mutual frailties and our geriatric naïveté as the light faded. Murph was self-effacing and always good at giving others reassurance and comfort.

He only lived three days after he was disconnected and died on his birthday. I know he did not want to go and enjoyed living but he felt he was given no choice by his genetics. Nobody wants to lose control. And nobody really wants to die. I want to live a million years and see what happens and if we ever figure out how to exist together and responsibly manage our resources and technology and how far we will reach into space. I know Murph wanted that, too, but he could not have it. Maybe nobody can.

In the fall, when our old campus was alive with people cooking outdoors and throwing footballs and the band was marching proudly along the banks of the Red Cedar River, the farm girl I married and our daughter and I, returned and found a spot for Murph's ashes. They glistened in the long grass and some of them scattered across the slow rapids beneath the falling leaves of October. Murph’s heart never really left Michigan State University, and he is now a part of it for all the remaining springs and autumns as the young gather to learn and dream and live.

Perhaps, that way, my friend, too, might live a thousand years.